My most archaic convictions make me prone to believe that, just as there is a reasonable anatomical and physiological continuity in the human species, there must exist a stubborn nucleus of mental continuity that allows us to find common intellectual ground with our predecessors and successors alike, if only traceable for a handful of generations.

It is with this conviction (or hope) that I dare to propose a code which establishes individually honorable and socially responsible limits for architecture, extending its territory to the indispensable arena of ethics, and perhaps of life.

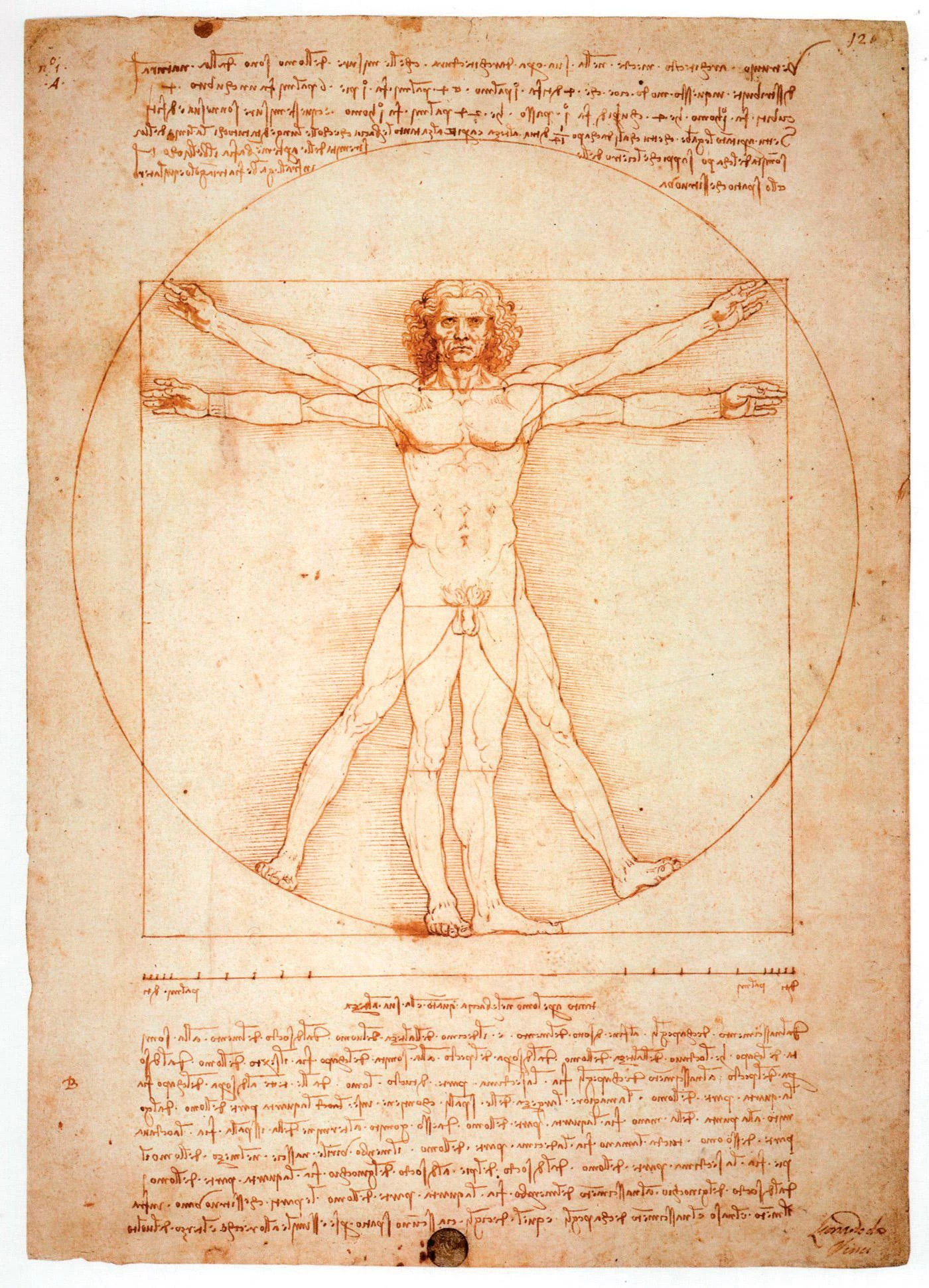

I call my proposition a Vitruvian code, by analogy with the precepts of Hippocrates, and have structured it along the three classical categories (firmitas, utilitas, venustas), adding a preface and a colophon.

To begin: The architect constructs for others, never for themselves; the architect looks for service, not applause; therefore, I will put architecture at the service of life, never life at the service of architecture.

First: I will build solid, durable buildings, conceived as much with today as with tomorrow in mind; I will use materials and energy judiciously, taking future generations into account; I will exercise caution in using the funds of clients, whether public or private.

Second: I will design on the basis of close study of the needs and desires of the building’s users; I will bear in mind the possible ways by which the public may use the building; I will be cautious in siting the building in its urban or rural context.

Third: I will give pleasure to the building’s users and observers through beauty; I will respect the historical or ecological values that give personality to cities or communities; I will not impose my tastes on users, clients, or the public.

And finally: If the circumstances of the commission do not allow me to uphold this code of conduct, I will abstain from building; because individual dignity is more honorable than professional opportunity; and because architecture is never as important as life.

I will surely be reproached for deontological maxims which are at once restrictive and trivial. They neither address the ambiguity of human conduct nor transcend tradition. They are, in effect, commonplaces. So familiar are these basic ideas that I considered the possibility of presenting them under the literary artifice of a found manuscript, so that they could draw authority from their supposed antiquity. Only by placing them at the infancy of architecture could such conventional, common, and almost banal concepts regain authority.

But it happens that highbrow and commercial architecture both stake out their respective territories outside this common ground, which then begins to acquire the fate of an imaginary place, often mentioned in statements but rarely present in actions. Paradoxically, this commonplace becomes utopian: a place that exists only in intention or in hypothetical projects. Under this light, the commonplace loses its pejorative connotation; it is no longer the busy path unworthy of those with the spirit of the explorer, but rather a meeting point for physical and social communities. The cliché is thus converted into an intellectual place of encounter that does not originate in laziness or routine, but in a firm decision to create a solid core of collective convictions: our common ground.

This text, comprising three precepts, a prologue, and an epilogue, is taken from the lecture the author delivered at his induction into the Royal Academy of Doctors on 12 November 1997.