With its elliptical floor plan and the light, metal visor which protects the grandstands, the Parisian stadium of Saint-Denis is an apt architectural representation of the congregational fervour of sport spectacles.

The metallic, light and taut Stadium of France resembles a flying saucer. Parked amid the highways and tracks of the Plaine-Saint-Denis, this spacecraft bristling with stairs can take in 80,000 persons, but will abduct half the planet’s population on July 12. Many await the matches of the final round with tenacious faith in a unanimous communion with the spheric icon, while others, tired of the stadium’s ominous odyssey, dream instead of a 4th of July marking an uprising against the alienating dependence on television sport. But while such an independence day eludes us for the time being, millions of fascinated human beings will continue to succumb in chorus to the kidnapping exercised by cloned screens, as voluntary followers of a ritual spectacle that dilutes us in an emotional, convulsive and universal pulse.

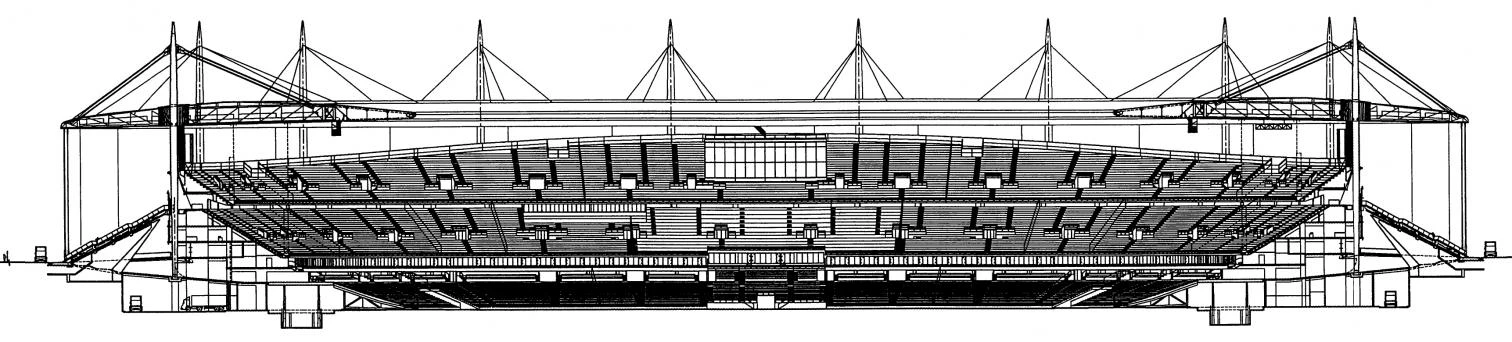

In the colossal tradition of the Grands Projets, and built in only two years on a budget of US$500 million, the stadium is a formidable engineering achievement, but also a very appropriate architectural representation of the congregational fervor of sport spectacles. Its elliptical, almost circular floor plan perfectly reflects the unitary character of the stage, which the cameras reproduce an infinite number of times, and its ingravid, halo-like visor protects the grandstands like a single closed canopy, crowning the site with an air-borne, dazzlingly sacred ring. Designed by the team of architects Macary, Zublena, Regembal and Constantini, the imposing building rises on the outskirts of Paris, close to the Abbey of Saint-Denis where the French monarchs are buried. But such an emblematic location is less important than the physical reality of the vicinity, a degraded scrap of urbanization surrounded on all sides by motorways.

The socialist Michel Rocard had wanted the stadium built at Melun-Sénart, 35 kilometers from Paris. Saint-Denis was a decision of Éduard Balladur’s conservative government, which late in 1993 organized the design competition that the MZRC team would win, over the likes of Jean Nouvel. Against the general tendency to situate large sport facilities outside the city, the idea here was to use the huge public funding available to regenerate a deteriorated urban zone. The operation was to include the cleaning up of soils polluted by the residues of old factories, the partial burying underground of a thoroughfare, and the allocation of an additional US$250 million to build two suburban line railway depots and renovate a metro station, in such a way that the stadium would be accessed mainly through public transport. In contrast to the interminable parking lots around American stadiums, Saint-Denis only has room for 6,000 private vehicles, and entrance passes to the World Cup inauguration match included return tickets for the local trains.

Accustomed as we are to regard stadiums as urban conflict areas – noisy during matches and even more so during music concerts, and causing traffic jams in the immediate surroundings – it is refreshing to see that they can also serve to improve the quality of the metropolitan fabric. Not a few decisions in the project were made in line with such a deliberate and optimistic reformism. The stadium, which can also accommodate athletics tournaments by pushing back the lower tiers, follows the Latin model of an ellipse around a racetrack, as against the Anglo-Saxon model of grandstands attached to the edges of a rectangular playing field. But instead of steep tiers closely encircling the arena, as in Jean Nouvel’s proposal in the initial competition, here the stands are placidly flattened out, so that the passion of the pot gives way to the comfort and security of the bowl.

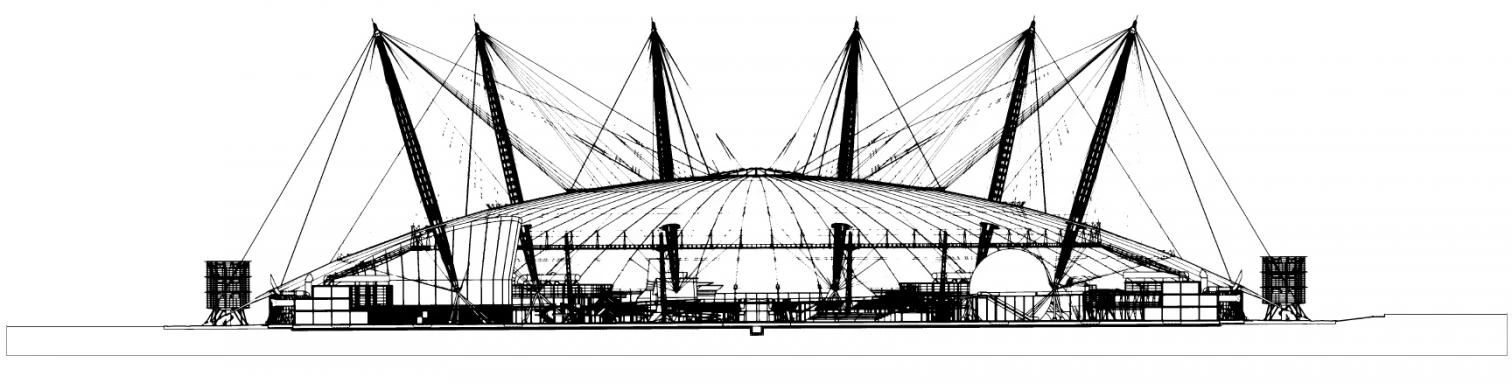

The Millennium Dome in London is another great precinct for leisure and spectacles with a circular floor plan and a roof suspended from masts, which in this case support a giant canvas reminiscent of a circus.

And against the pragmatic American and Japanese tendency to cover the entire precinct of the sport facility with fixed or mobile structures – alternately designed in various shapes such as fans, pupils, or diaphragms – guaranteeing that scheduled events are held whatever the weather, so that television networks and advertisers need not worry, at Saint-Denis the spectators of the games are roofed by a huge canopy that nevertheless allows the free circulation of air and lets the sunlight in.

Without a doubt this ring-shaped canopy is the stadium’s most characteristic element, and that which best expresses its character. Suspending from 18 masts, the flat metal ring – stretched over like a gigantic porch – covers the staircases that jut out from the steel mesh facade, and stretches inward over the stands up to the line where the grass begins. Incorporating spotlights and megaphones along its inner edge, the ring closes so much over the playing field that glass has had to be used in its innermost segments, making the lighting of the arena more homogeneous. It also serves as a reflector of artificial light, and the gleam at night emphasizes its immaterial condition as a floating disc, spaceship or magical halo alluding to the planetary communion of sport.

Beneath this unanimous ring of universal solidarity, Spain’s national soccer team had the courtesy to lose to its French hosts in the friendly game that inaugurated the stadium on January 28. That had been coach Javier Clemente’s first defeat in a long time, and after the latest big fiasco, who knows how long it will take for his eliminated boys to try their luck anew on the green of Saint-Denis. But perhaps rings are a reference to Saturn, and maybe this is why they are returning from the saturnalia with rather saturnine spirits. This Saturn does not devour his own children, but his neighbors’.

France, 1; England, 0

France’s and Britain’s great turn-of-century constructions have something in common: the Stadium of France and the Millennium Dome are colossal precincts for leisure and spectacles, elliptical and circular on plan, both with a roof suspending from masts. But whereas the stadium of Saint-Denis has created a powerful symbol with the luminous geometry of its ring-shaped roof, the structure being erected by the team of Rogers at Greenwich is but the canvas of a circus that dares not pronounce its name, and that avoids a hanging shape by feigning the prestigious bulk of a dome that is not.

While the 18 Parisian masts stand vertically and serenely with an old and casual severeness around the oval of the concentric crowd, the 12 London masts rise playfully amid the thematic segments of a trivial exhibition. And while the French project imposes its neat categorical shape on a chaotic environment and domesticates its scale by sinking 11 meters into the ground, making it possible for the ring to be set at the moderately monumental height of 31 meters, the British project blurs its perimeter with capricious sprinklings of tents and makes a main visual reference of masts and bundles of cables that soar to an outrageous height of 100 meters. Moreover, even with similar dimensions (in both cases, the diameters are slightly over 300 meters), the permanent stadium has incurred a cost that is less than half the budget established for the temporary dome...

Given the British determination to celebrate the coming millennium on the meridian of Greenwich, it is no wonder that the French have decided to give physical expression to their own meridian in Paris – established by Louis XIV, adopted by the Republic in 1799, and situated at 2º 20’14’’to the west of Greenwich – by planting trees all along the line that stretches North to South, from Dunkerque on the Channel to the Catalan border, in a gesture of illuminist land art that reconciles us with Chauvin.