Summer arrives with storms. A telegraphic chronicle of three days in June presents Europe’s fits and starts at a moment of tribulation that awakens old phantoms. In the first volume of his masterly history of the continent (To Hell and Back: Europe 1914-1949), Ian Kershaw attributes the tragic descent into the netherworld that the two world wars were to the ominous coincidence of four powerful forces that razed Europe like the four horsemen of the Apocalypse: the explosion of nationalism, demands for territorial revision, acute social conflict, and a protracted crisis of capitalism. It makes sense to wonder if these same forces, though perhaps less virulently, are not present at this hour of the continent, driven like a century ago by sleepwalking elites.

The British campaign to leave the European Union used dramatic images of the flow of refugees on their way to Germany, while the Dutch Rem Koolhaas defended in Spain the political value of the European project.

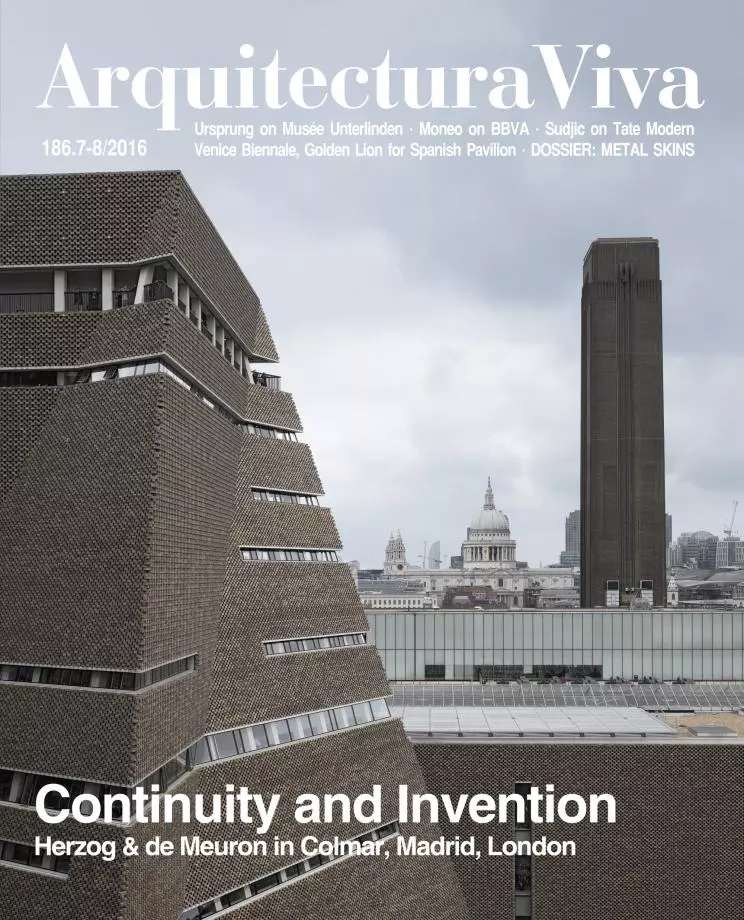

Our chronicle has its first sketch in London, where on 16 June the new Tate Modern opened with a multitudinary party that extended from the old museum (now Boiler House) and the Turbine Hall to the observation deck that crowns the enlargement (called Switch House), with a 360-degree view over this sleepless metropolis of changing skyline, on the banks of a River Thames where the previous day saw a bitter but bloodless naval battle waged between Brexit and Bremain supporters. Nicholas Serota – who is stepping down as director of the Tate galleries, after almost thirty years at the helm, to become Chairman of the Arts Council England –, takes pride in having brought contemporary art to a city that ridiculed it two decades ago, but in conversation with Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron amid works of the now inevitable Louise Bourgeois – in one of the inaugural monographic shows – we wondered with melancholy if this new Tate building might not be the last hurrah of cosmopolitan England, and the art party eventually dispersed under a torrent.

A week later, on the 22nd, in a Paris that managed to deal with the floods caused by the rise of the waters of the Seine, Dominique Perrault was admitted into the Académie des Beaux-Arts beneath the dome of the Institut de France, received by the Aga Khan, whom we had coincided with at a meeting in Geneva, fifteen days before, as members of the jury of his architectural award, which has for four decades now been opening for Europeans a fascinating window to the Islamic world. Arriving later at this big party of French architecture was the President of the Republic – on what was a difficult day for him, the eve of a general strike that would wreak havoc in Paris traffic and in many French airports – and François Hollande courteously inquired about our Sunday elections, which prompted mention of the next day’s British referendum as perhaps the biggest risk for a continent overwhelmed by mass immigration.

Still under the impact of the unexpected results of the British polls of the 23rd and the Spanish ones of the 26th, on 29 June the 4th International Congress of the Fundación Arquitectura y Sociedad – held under the motto ‘Architecture: Change of Climate’ – kicked off in Pamplona with Rem Koolhaas and King Felipe VI as the star figures, and neither disappointed: the architect from Rotterdam upheld political activity as the way to address the cracks that populist nationalism is opening in the European Union, and the monarch stressed the urgency of the challenges created by climate change. But both mentioned – as I myself did in the presentation of the congress – the previous day’s attack in Istanbul’s airport, a terrorist action of ISIS that two days later was to hit Dhaka and another two days later Baghdad, shaking our consciences and exposing our vulnerability. Despite the king’s remarks to a group of architects that we can perhaps still hope for what The Economist calls Breversal, Europe finds itself at a historic crossroads, and in the northern hemisphere we begin summer faced with a menacing landscape under clouds of blood and bleakness.