Switzerland is indeed an exceptional country. Exceptional in its affluent fortress of caution, and exceptional also in a stubborn reluctance to linkage, this Alpine haven is at the same time a precinct of exclusive privilege and a redoubt of resistance towards integration, a singular territory that the rest of the Europeans necessarily contemplate with mixed feelings of admiration and resentment. The exceptional character of both its placid prosperity and its splendid isolation render it at once excellent and excentric, unsurpassable and unsupportive. Protected by the abrupt relief of its physical geography and by the silent labyrinth of its financial topography, Switzerland defends itself from the wrought-up waters of Europe as Europe defends itself from the convulse currents of the world: islet of calm in a small conflictive continent, it must of course be seen as the shelter of fleeting heterdodoxes it has so many times been; but it should be perceived even more as the armor plating of obscure traffic it still is.

Archaic and arbitrary, this exact state of precise communications and inscrutable annotations has witnessed the cracking of its shield of security and the bruising of the skin of its self-esteem. The catastrophes of the Alpine tunnels have blocked essential arteries, while the crevices in banking discretion have wounded obstinate dogmas, simultaneously strengthening its inaccessible insularity and its accessibility to scrutiny. The choleric assassination of 14 congress members at the canton of Zug has shown that the Helvetians are not immune to the morbid virus of trivial violence, and the temporary relocation of the Forum of Davos to a hurting and surveyed New York has made evident that not even at the Grisons may the peace of citizens be guaranteed. Last but not least, the crisis of Swissair has devastated a business and political symbol, dragging along in its disrepute the government and the two largest banks, UBS and Credit Suisse, responsible of a humiliation which has fractured the somnambulistic pride of a self-absorbed nation.

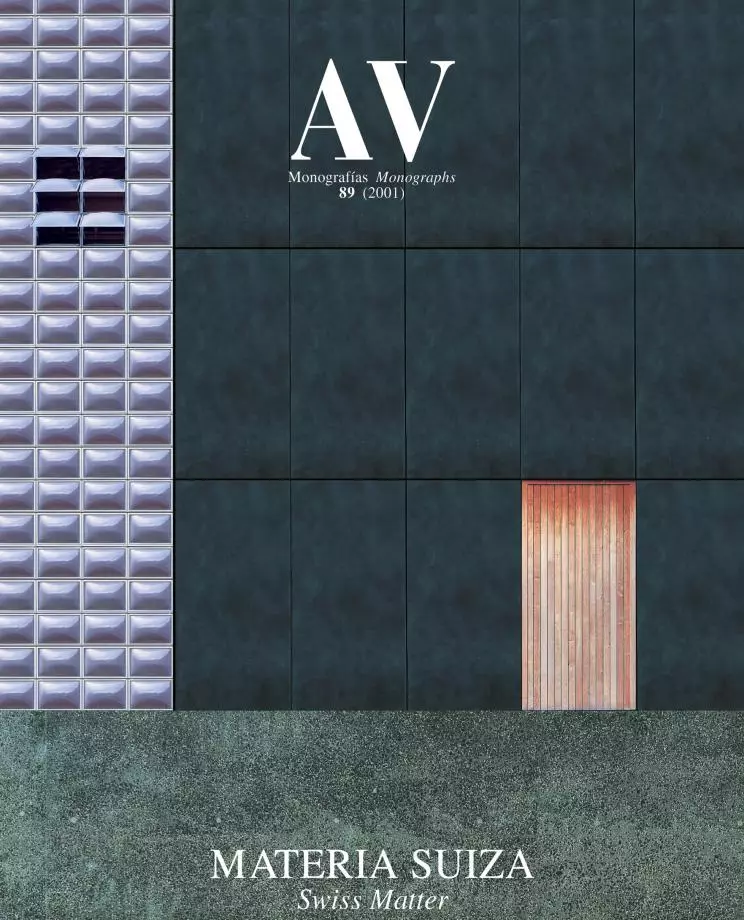

Flawless builder of an architecture weathered by a generous budget and a demanding climate, Switzerland has delivered a harvest of exquisite works which have made us pilgrims of the Alps, palmers of Basel or Zurich, and devouts of a cluster of scattered sanctuaries which attract the attention of the onlookers to villages of laborious access. Distractedly disdainful towards engineering and deliberately deferential towards the landscape, these tough and elegant projects enter into dialog with Swiss referents without scorning the vehement adhesion to a timeless cosmopolitanism; but they were excluded from the the last edition of the European Mies van der Rohe Prize for their voluntary detachment from the common institutions. Exceptional in their strongbox autism and exceptional in the beauty of their tactile matter, the Swiss buildings of today have their clocks held-up in the intact moment of their exempt exception: exempt from history, exempt from drama and, until yesterday, exempt as well from exceptional fear.