Giancarlo Mazzanti takes play seriously, perhaps like no other architect since Aldo van Eyck. The Dutch built more than 700 playgrounds in Amsterdam over the course of 30 years, integrating those ludic and abstract spaces in the everyday life of a city that was recovering from the trauma of World War II, and the Colombian tries to repair the social scars of inequality and violence with parks for children and playing fields that are scattered throughout the country carrying a message of regeneration and hope. Unlike the innumerable playgrounds built by Robert Moses in New York, which could be imagined to be inspired by the homo faber theorized by Henri Bergson in their physical separation between space for work and space for leisure, the playgrounds of Van Eyck owe a lot to the homo ludens coined by his fellow countryman Johan Huizinga in their determination to blur the boundaries of play so that it can colonize urban life, and Mazzanti takes that vision a step beyond by turning the project itself into a serious game.

Serio ludere is something more than an oxymoron used by Renaissance humanists and recovered by Omar Calabrese to describe a neo-Baroque era where the arts are fertilized by the orderly chaos of the sciences, from the dissipative structures of Prigogine or the fractals of Mandelbrot to the catastrophes of Thom. By contrast, the serio ludere of equipo Mazzanti faces the challenges of design articulating social cohesion through the active participation of the community in games that use modular systems and assembly rules to reconcile organization with versatility, extending the connection between play and the avant-gardes that offers so many examples – from the education with Froebel blocks of Wright, Le Corbusier or Fuller to Itten’s Vorkurs at the Bauhaus –, and which architect Juan Bordes has researched in depth. If childhood and art are associated since the dawn of modernity through the toys designed under the influence of Pestalozzi, Mazzanti gives new life to that approach with the serious games inspired by Malaguzzi.

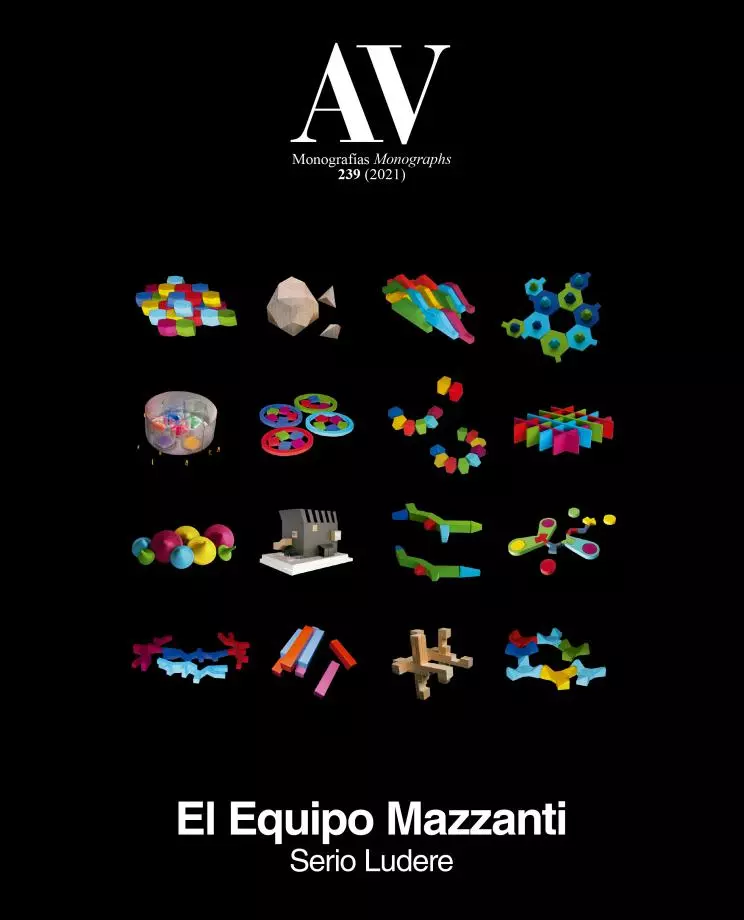

Among the exhibitions on show in Madrid this fall is ‘The Magritte machine,’ where Guillermo Solana presents the work of the Belgian artist recalling the fantasy of the painting machine to explore the method that allowed the artist to multiply the variants of his canvasses from a few motifs, and even generate them through a random and combinatorial game of addition, subtraction or permutation. Though far from surrealist poetics, it is tempting to identify a ‘Mazzanti machine’ to explain the composition procedures of the team gathered by the Barranquilla architect: be it children’s parks, sports venues, or the vast biomedical campus of Rome, the result does not come from a closed design, but from elementary modules combined by rules. Those are the fields – delimited in their dimensions and governed by rules as are sports competitions – on which the team plays, and those are the political and social contexts which frame the work of innovation and research of an architect who takes play very seriously.