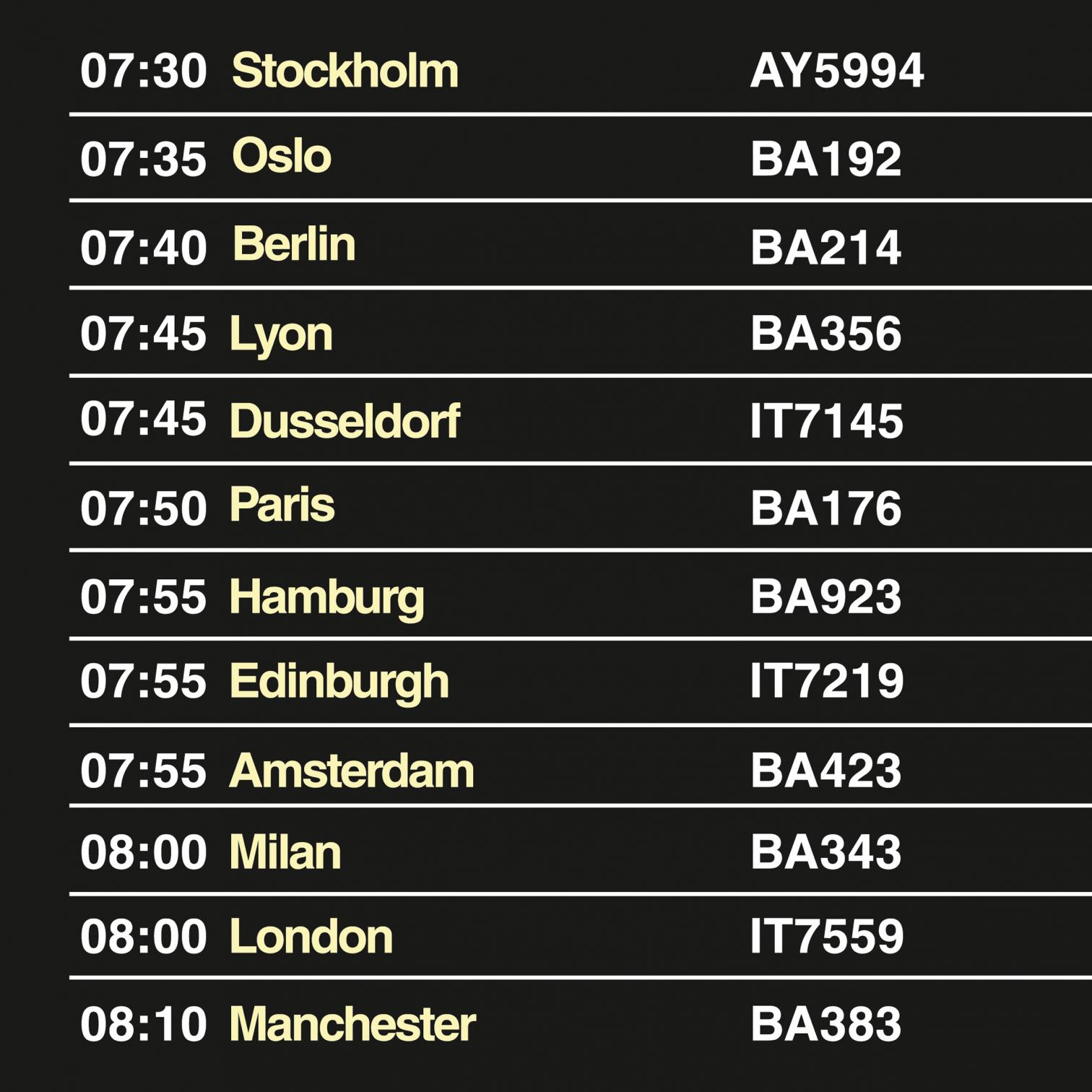

Spain exports architects, but also architecture. In the crisis, the media have turned the spotlight on the youth exodus: thousands of architects with a good polytechnical training who have sought in other European countries, in Latin America, the Gulf or China the opportunities that Spain does not offer. But this professional migration is less traumatic than those of the past, because the Erasmus generation is at greater ease around the world than the previous ones, and because the cheap flights and the communication means at hand let them stay connected and close wherever they are. If they return, they will have better technical and language skills, enriching the country with the diversity of their professional and cultural experience. The current clamor against the ‘forced exile’ or the ‘brain drain’ does not seem entirely justified: the young architects outside Spain are an asset, and the group most capable of adapting to an uncertain environment.

Aside from this export of young professionals, Spanish architecture has tried to ride the current economic winds by exporting work and talent: from the studios with international renown to the large offices with management capacity, and even the emerging studios or recently graduated architects, all of them look abroad for the projects that are hard to find either in the public or in the private sector, given the country’s situation. Competition is indeed fierce, regulations often labyrinthian, and construction customs always different, but in the end architecture is an Esperanto that makes us all feel like speakers of a common language. The examples published in this issue, all of them located in Europe, stress the advantages of working in a continent without national boundaries, and underscore the critical importance of this shared political project, even though the flames of European enthusiasm of not so long ago are now only embers that need to be revived.

Along with these two exporting flows, of people and of services, Spain has also sent abroad a large academic representation that is joining the most important American and European universities, and this qualified migration of teachers strengthens the professional and personal ties that weave this wide network. Quite some time ago I described our own as a ‘peninsula without perimeter’, understanding that a history shaped by centripetal and centrifugal migrations is ill at ease with isolation and closure. The demographic systole and diastole we are witnessing of late can be interpreted as a heartbeat or as a convulsion, as the long waves of our common adventure or as a perfect storm in a country that has gone from ecstasy to exasperation. Be it as it may, this debt-ridden and exhausted country needs to export – professionals, projects or professors –, and in doing so architecture participates in the choral effort of economic and social regeneration.