In February 1951, Le Corbusier went on his first trip to India. The Government of Punjab – the state that emerged in the northwest after the split of the British Raj – had tasked him with the urban planning of the new regional capital, Chandigarh. As was his habit, he took along notebooks of different sizes in which to record his reflections, the discussions held at work, preliminary design sketches, and drawings of observations he made in the course of his travels. That initial visit to India produced four such logbooks: the small E18 and E19 carnets, the Nivola 1 notebook, and the ‘Album Punjab,’ heretofore unpublished.

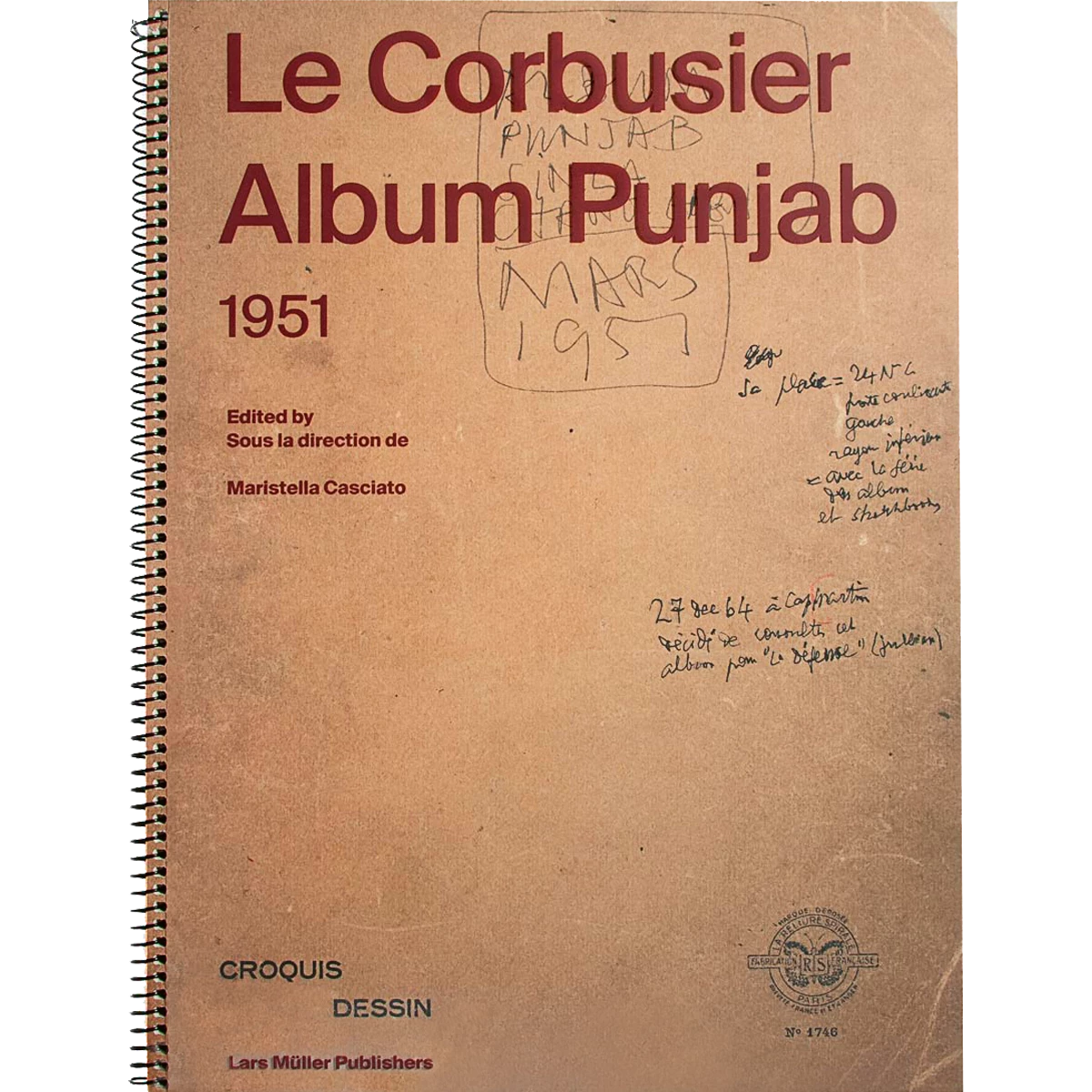

They have recently been released together in two volumes wrapped in transparent acetate. The first one, a bilingual (French/English) edition, is an introduction that recounts the development of the commission (entrusted to Le Corbusier and his team, which included Maxwell Fry, Jane Drew, and Pierre Jeanneret, alongside the Indian engineers P.L. Varma and P.N. Thapar), the journey, the organization of teamwork, and the notebooks filled up by the Swiss-French architect, with special attention on the content of the album. Pages are shown with Le Corbusier’s illegible handwriting transcribed, and accompanied by a rigorous interpretation by Maristella Casciato, senior curator and head of architecture special collections at the Getty Research Institute, who explains the annotations and drawings. There are also some of the hundred black-and-white photographs that Pierre Jeanneret took of landscapes, traditions, and ancestral architecture, giving us insight into the group’s fascination with India.

The Album Punjab is reproduced in facsimile form in the second tome, with the same dimensions and spiral binding. There Le Corbusier left a wealth of notes (we learn, for instance, of the presence of Varma and Thapar), but especially drawings. His interest in archaic civilization (he drew bovines and elements of vernacular culture, such as cots made of braided fabric, vases, kilns, stone mills, verandas, and bonds of pressed brick) is interwoven with early sketches for Chandigarh: the outlines and dimensions of the grid, the schemes of the seven roads, the silhouette of the complex against the Himalayas, drafts of institutional edifices and of housing floor plans and sections, or construction arrangements based on Catalan timbrel vaults, not to mention allusions to his own architectural principles, such as the house on pilotis, the garden terrace, or the brise-soleil. Most of the drawings are concise, rendered during work debates or while moving around the country, but they show that he had already perfectly intuited the contour of the city, its functional layout, and the buildings that would give it significance.

This exceptional publication allows us to enter Le Corbusier’s design process, to feel his ideas, his explorations, his hesitations and doubts, his opinions on Albert Mayer’s preceding proposal. The album is the synthesis of a fascinating experience, and thanks to it we can see how the master saw what was to be the blueprint of his great urban project.