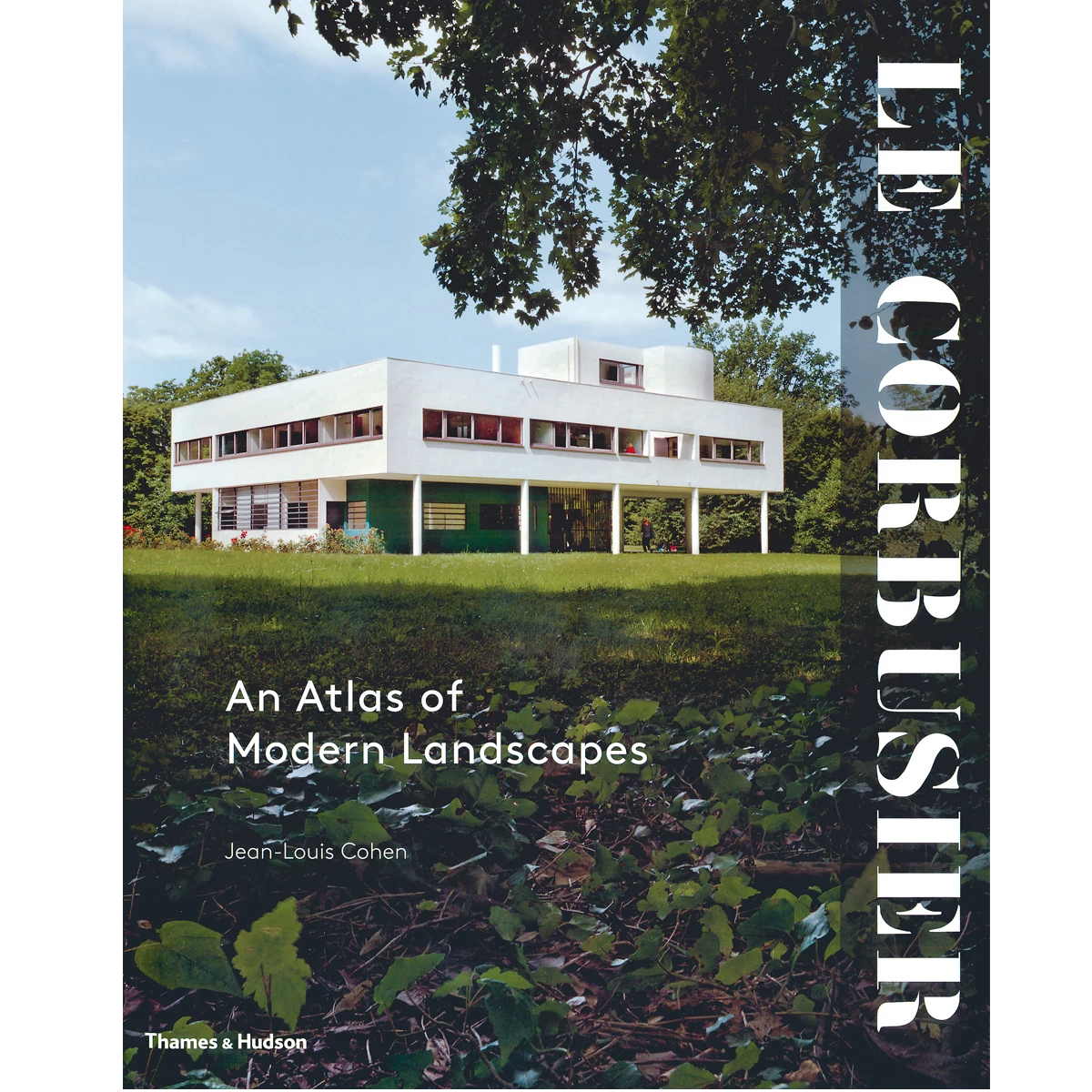

Half a century after his death, the bibliography on Le Corbusier is truly overwhelming, and in this section we have tried to cover the most significant examples. But the book by Jean-Louis Cohen, which served as catalog for the MoMA exhibition that has later traveled to Barcelona and Madrid, deserves special attention because it is a genuine revision of the master’s legacy. Conceived as an atlas documenting his travels and his works on four continents, the volume is a biographical journey through Le Corbusier’s career, from his beginnings in the Jura to the final projects in India or Japan, a voyage Cohen embarks on in the company of a fine group of specialists (including Stanislaus von Moos, Jacques Lucan, Juan José Lahuerta, Tim Benton, Mary McLeod, Josep Quetglas, Anthony Vidler, Antoine Picon, Jorge Francisco Liernur, or Carlos Eduardo Comas, besides the exhibition’s co-curator, Barry Bergdoll), and the result is a formidable work throwing new light on many issues.

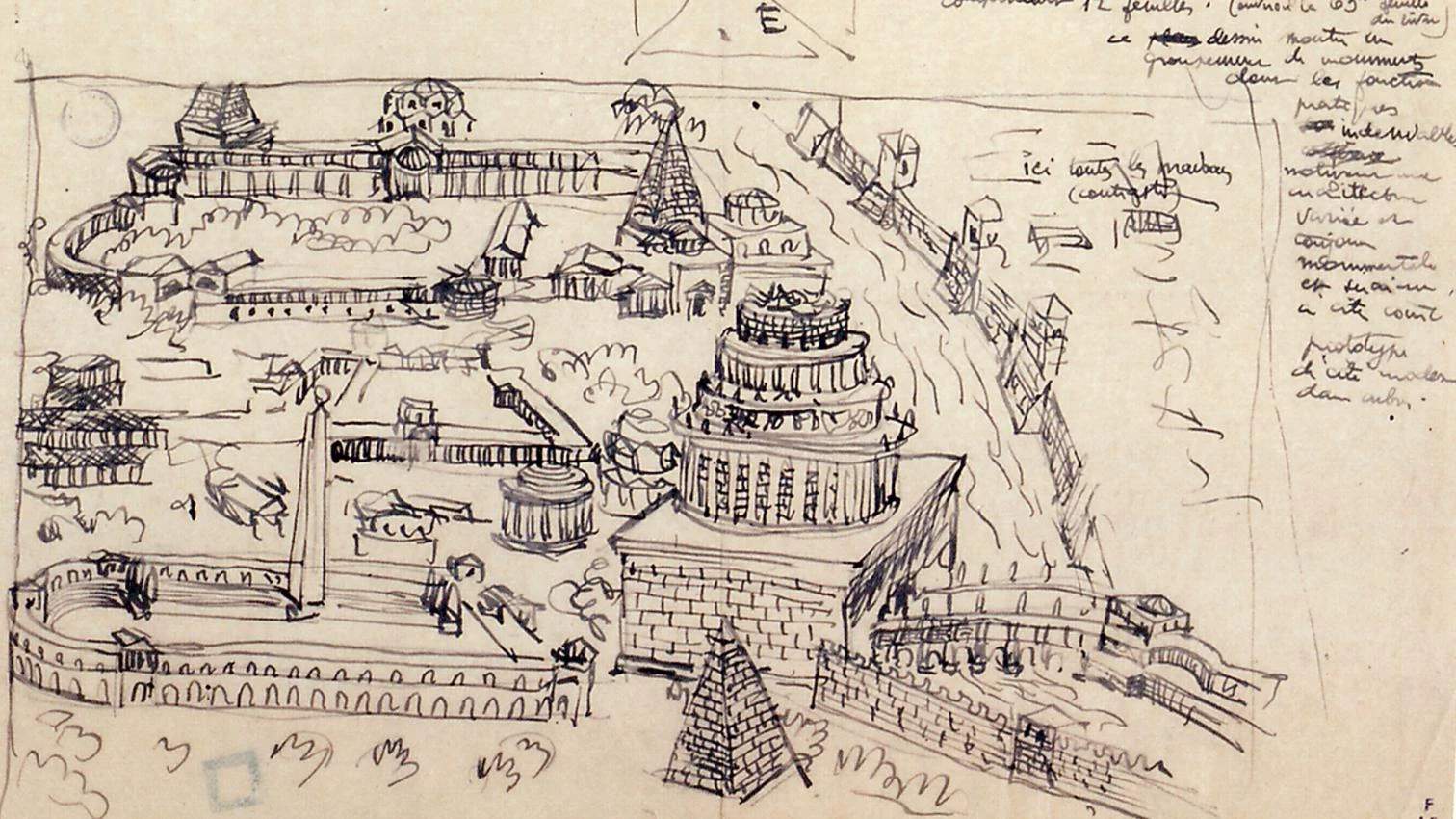

The guiding thread of landscape seeks to change the usual perception of Le Corbusier as an author of free-standing, autonomous works oblivious to the places they are in, and to achieve this it puts strong emphasis on the relationship between the buildings and their locations, essentially through drawings and sketches of the landscape and the way it is framed from the interiors. The relationship with landscape is thus more visual than morphological, for although it is subject to the gaze, it does not in any significant way change the building’s layout, paradoxically confirming Le Corbusier’s conventional vision, which he himself expressed vividly in the famous drawing of Rome that he published in Vers une architecture, inspired by an engraving by Pirro Ligorio, whose image of the anteiquae urbis as a collection of autonomous pieces made him propose it as a “prototype of the modern city.”

Cohen is keenly aware of this, and his own presentation explains that landscape “involves neither geographic interpretation nor [its] active or reactive presence in his projects” because it is essentially a metaphor and a source of analogies and aphorisms. Bergdoll himself, who gave us a convincing Gartenkultur picture of Mies in the MoMA’s 2001 exhibition, acknowledges here that the relationship between building and place in Le Corbusier was based on “his concept of vision, of the way he looked at the world on journeys.” More a chronological account than a proper atlas, and more a viewing of landscapes than a landscape view of Le Corbusier, the book is at any rate a colossal critical and historical achievement (probably the most significant since the publications sparked by the centenary in 1987) and elegantly settles the New York museum’s long-standing debt to the master from La-Chaux-de-Fonds.