The fact that Le Corbusier, peintre à Cap-Martin (Éditions du Patrimoine, 2015) has now been published in English is a further step in the reexamination of Le Corbusier that we have been seeing for some time now, and specifically situates his artistic work where he wanted it: at a place from which to rethink architecture.

In 1937 he visited Roquebrune-Cap-Martin and Villa E-1027, owned by Jean Badovici and designed by Eileen Gray. Impressed with the house on the Mediterranean, he went back in 1938 and 1939. He drew up the Bogotá masterplan there in 1949, then returned yearly. In 1951, having come to an agreement with Thomas Rebutato, he annexed the Cabanon to the restaurant L’Étoile de Mer and built five ‘Unités de camping’ in 1957. Both the interior and the exterior of these constructions became canvases for Le Corbusier’s painterly explorations.

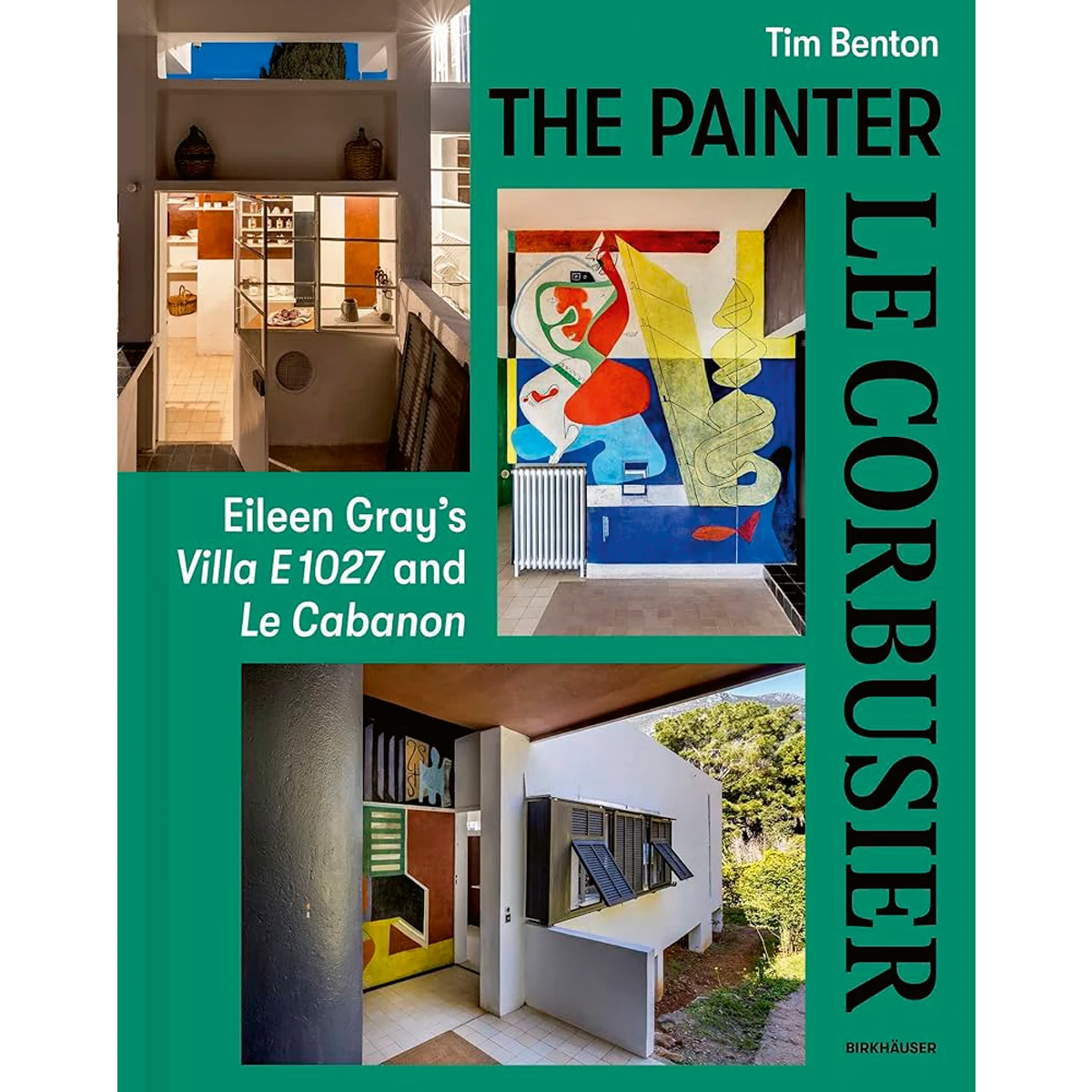

Focusing on Le Corbusier’s artwork in this special place, Tim Benton offers a synthesis of the evolution of his pictorial work, which in that period took on more personal shades. The woman and the nude appeared as subjects, and a purist palette gave way to vivid primary tones. It was also there that he tried painting murals. The influence of De Stijl, memories of medieval and Renaissance frescoes, the rise of murals as socially committed art, and his imminent foray into tapestries explain his journey from denying a niche for painting in his early architectural works, to being put beside Fernand Léger in the murals of Badovici’s house in Vézelay (1936).

The book makes a stop at the six frescoes and the graffiti done in Villa E-1027, in addition to the paintings he did in the restaurant and the Cabanon, tracking the origins of the motifs and forms and their reappearance in other contexts, such as Le Poème de l’angle droit, and in iconographic series like the Taureau, spelling out their meanings and variations. It also addresses the controversy about the ‘aggression’ that these mural paintings allegedly did, as much on the house as on Eileen Gray herself. Though after the war and under Gray’s influence Badovici expressed disagreement, Benton reveals that he heartily accepted them at first, and that there is no evidence that Le Corbusier bore any grudge against Gray or against the villa he always admired.

The book is bracketed with a foreword and a coda by the presidents of the two institutions involved in this heritage site: Antoine Picon of Fondation Le Corbusier and Magda Rebutato of Association culturelle Eileen Gray – Étoile de Mer. Along with images by Benton himself, the photography is a work of Manuel Bougot, excellently printed in a way that allows full appreciation of Le Corbusier’s painterly work, its diversity of registers, its recurring themes, its different techniques, and its rapport with or antagonism towards architecture. This artistic work – which Le Corbusier insistently advocated as a laboratory for architectural ideas – is upheld as complex and significant in the evolution of modern art and architecture.