Cracks in the Myth

Fifty years after his death, exhibitions and books revise Le Corbusier’s life and work, shedding light on the master and also on the links between architecture and politics.

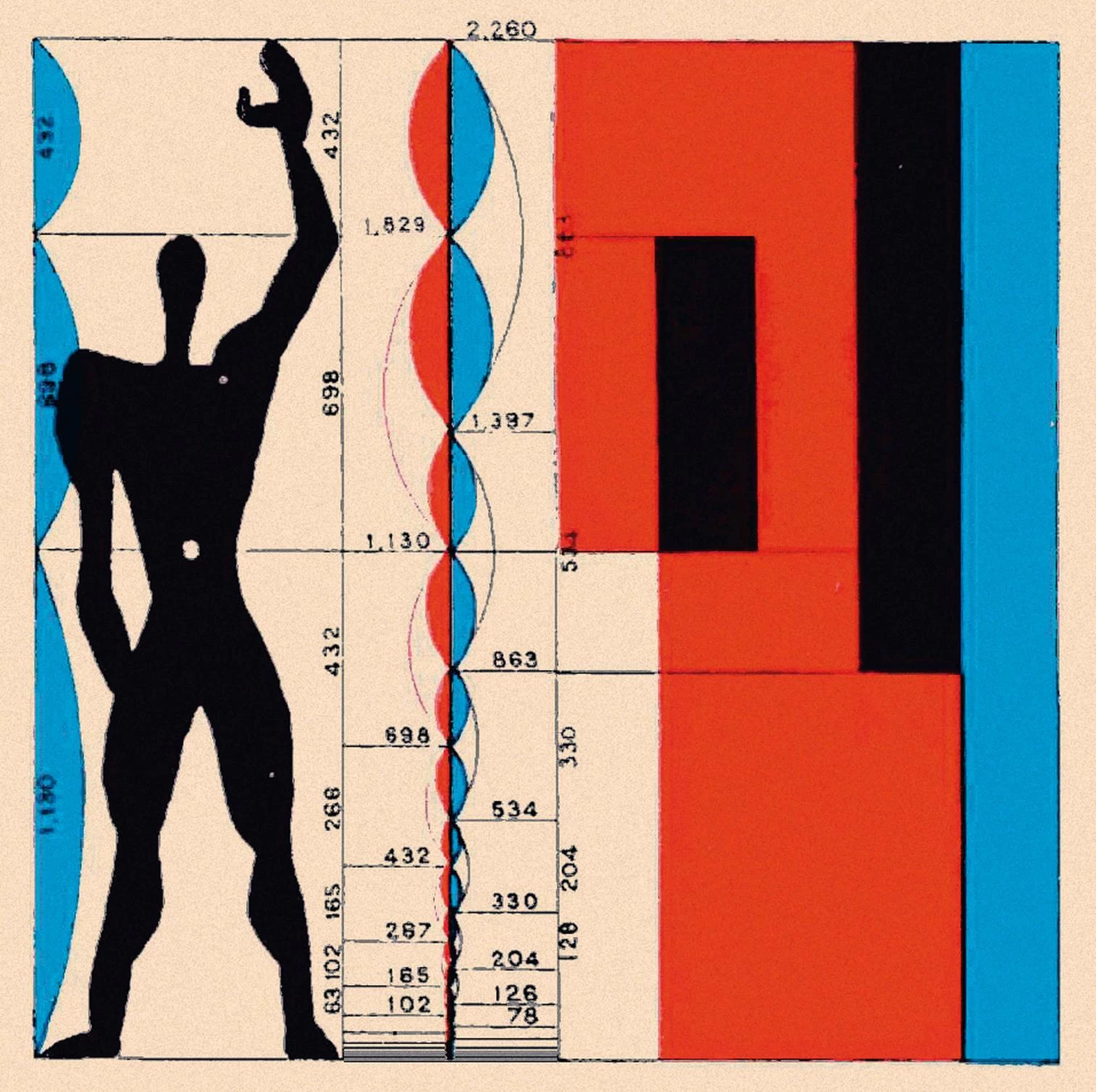

Half a century after his death, Le Corbusier still stirs the waters of debate. The major exhibition held at the MoMA in 2013 emphasized the landscaping aspect of an oeuvre that tends to be perceived as being removed from context; the no less important show put on in 2015 at the Pompidou uses the Modulor to present a humanist view of a master often judged as the author of dehumanized architecture; and in contrast with these monumental celebrations, a new English-language biography and three texts published in French highlight the ideological and political aspects of a life journey that is both dazzling and somber.

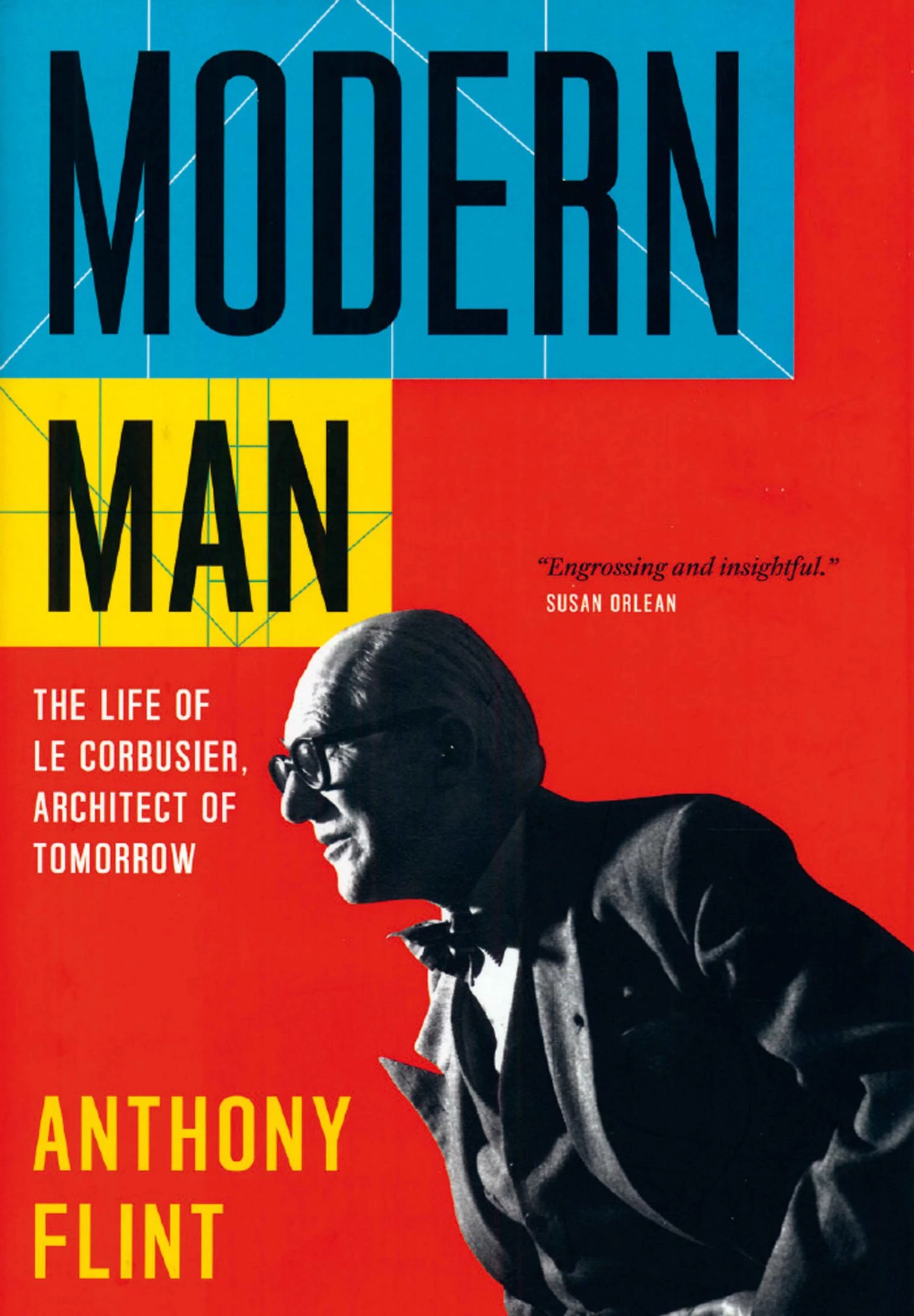

The biography by Anthony Flint, intended for the public at large, presents Le Corbusier as the first ‘starchitect’ and has no qualms about using celebrity and sex to capture the reader’s attention, starting his story with the architect and Josephine Baker aboard the liner Lutetia, which in 1929 was the scene of their mythical romance. Acknowledging his debt to Le Corbusier scholars like H. Allen Brooks, William Curtis, or Jean-Louis Cohen, Flint offers a compact biography that will increase knowledge about him in the Anglo-Saxon world, but cannot replace the colossal work of Nicholas Fox Weber (Le Corbusier: A Life), the essential source on the master’s life since it came out in 2008.

In recent years, the publication of a good part of Le Corbusier’s copious correspondence has provided fuel to his biographers, and made it possible to chart his intellectual concerns and ideological links with greater precision. The main dark area, referring to the eighteen months between 1941 and 1942 that he spent in Vichy working for the collaborationist regime of Marshal Pétain, had already been addressed by American authors like Robert Fishman in 1977 and by Mary McLeod in her dissertation of 1985, but had not affected his reputation significantly. However, this picture has suffered a media upheaval with the three works published in France this spring.

The most important is the one by the critic and historian François Chaslin, a thick volume of exceptional literary quality which is a reckoning with a figure much embedded in the author’s life. As he points out, it is neither a biography nor an academic work, but an impressionist portrait, painted with light strokes on the canvas of recent French history. In the course of this promenade architecturale, which advances in zigzag “like the path of the donkey,” offering dramatic or picturesque views, Chaslin admits to stumbling into the Vichy route, and feeling forced to consult other archives for documentation on a historical period no one wants to poke into, and the result is devastating. Both Le Corbusier’s fascist sympathies and his anti-Semitic attitudes appear in the text under a blinding light: from his close friendship with his neighbor, the homeopath Pierre Winter, defender of the healthy body and founder of the French fascist party, to the adventure of the magazines Plans and Prélude, both linked to parafascist movements, the architect’s political agenda can no longer be dismissed as simply generic, nor be concealed by academic self-censorship.

The Pompidou show focussed on the Modulor, the biography by Flint presented the master to the general public, and the three French works critically revised the political opinions and activity of Le Corbusier.

The book by the journalist Xavier de Jarcy sums up very well its intentions in the title, Le Corbusier, un fascisme français, because far from presenting the architect merely courting totalitarian regimes for commissions, it describes a political and urbanistic ideology totally in tune with the activism of his group of friends – a circle belonging to an authoritarian Right which some contemporary historians situate in the orbit of fascism –, which included Dr. Winter, his loyal engineer François de Pierrefeu, and the famous surgeon and author Alexis Carrel, an advocate of eugenesia whom Le Corbusier admired deeply. The book is demagogic to some, but it presents the violent beauty of Taylorist techno-fascism persuasively, and describes in colorful style the Vichy period, the fascination with corporatism, and the architect’s candid opinions on figures like Hitler, Mussolini, or General Primo de Rivera.

No less militant is the essay by the philosopher Marc Perelman, who in interpreting Le Corbusier’s vital and intellectual trajectory judges him with ferocity as a rigid authoritarian determined to mechanize the body through sports and the ‘grand stadium’ that is the Ville Radieuse, a ‘cold utopia’ which in our times has engendered “worldviews as terrifying as those of Rem Koolhaas.”

Chaslin quotes José Ortega y Gasset, the author of Meditations on Quixote, to explain the life of the master as a process of identity building, using the philosopher’s idea that every man must invent himself by idealizing the character he is to become.“Original or plagiarist, he is his own novelist.” Le Corbusier, who in 1945 had his copy of Don Quixote bound with the hide of his dog, had a good idea of how to construct a hero’s story, and the cracks now appearing in his pedestal are no threat to the survival of the legend.