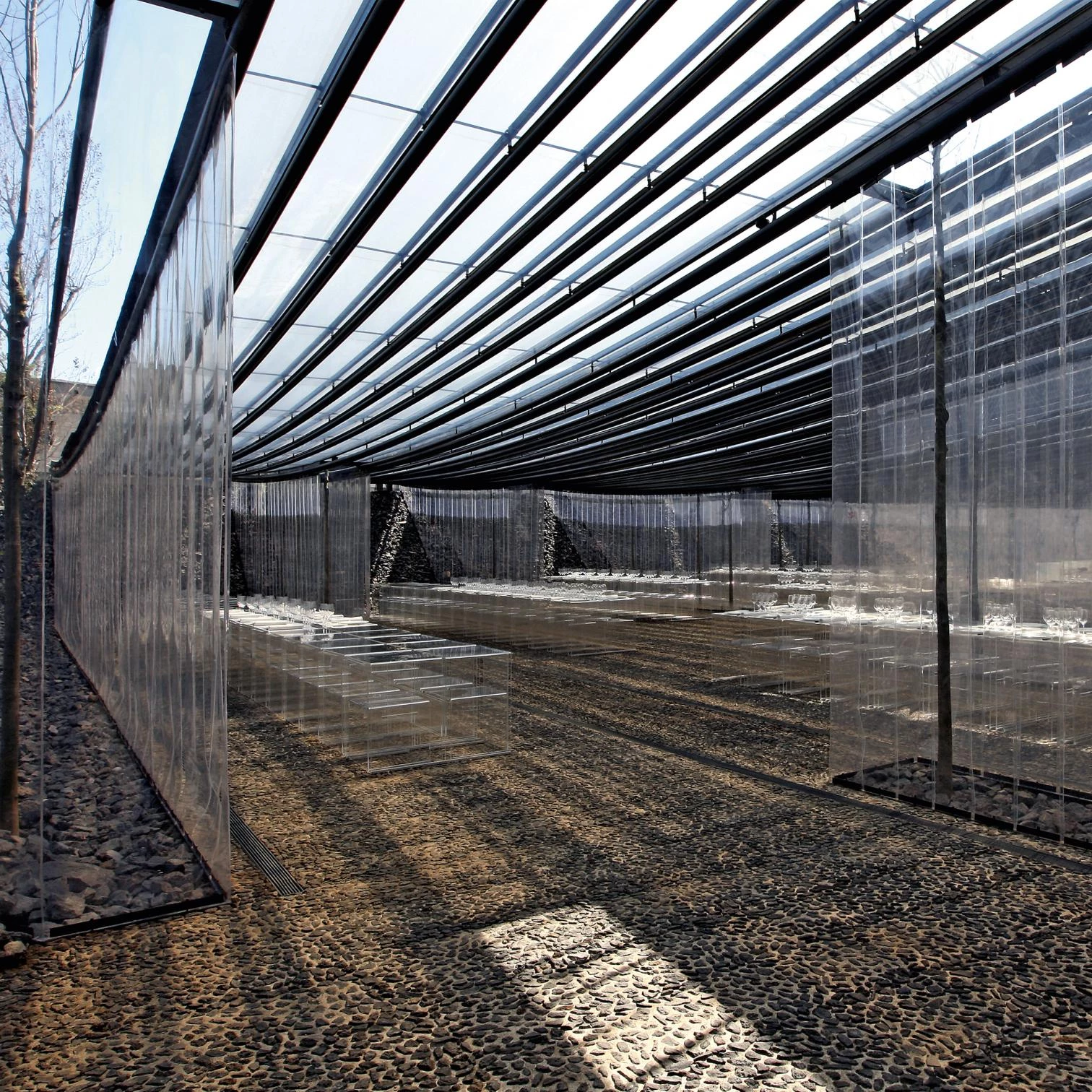

Matter is today very spiritual. In a world swamped with digital images, the return to the physical, tactile humility of primary materials becomes a pilgrimage to the essential sources of construction, a path of knowledge that drains the superfluous and elevates through descent. Paradoxically, the economicist materialism of our time asserts itself through a pervasive immaterial realm of flickering screens that offers objects both desirable and deleterious; emotive and intellectual redemption demands rejecting that fanfare of images and embracing a Franciscan search for material simplicity, a path of relinquishment that finds its fountain of architectural wisdom in the essential.

Likewise, the local is also the most universal. As the Spanish philosopher Miguel de Unamuno warned a century ago, a universal dimension can only be attained delving into one’s own roots, and we find more relevance and truth in the intrahistory of ordinary people than in major events: there is more shared emotion and authenticity in the renewed use of traditional materials than in the spectacular production of built icons for global audiences. Against the visual cacophony of this accumulation of loud symbolic forms, the physical intimacy of proximity goes beyond its local condition to become cosmopolite, in another architectural oxymoron that reconciles skin and sight.

If the material is local, its cultural significance is combined with its landscape affinity to rescue the most exclusive from their aura of privilege, freeing them from the solemn lazaret of pomp and luxury. Alejandro de la Sota’s commitment to modernity made him reject ‘noble’ materials, but he had to use marble in the Civil Government of Tarragona because it was the competition brief’s requirement for an official building, and he managed to ease his mind only after talking with José Luis Sert, who reassured him saying that any material taken from the ground and placed on top of it was acceptable, and Sota’s Borriol marble, extracted from a local quarry, met this condition.

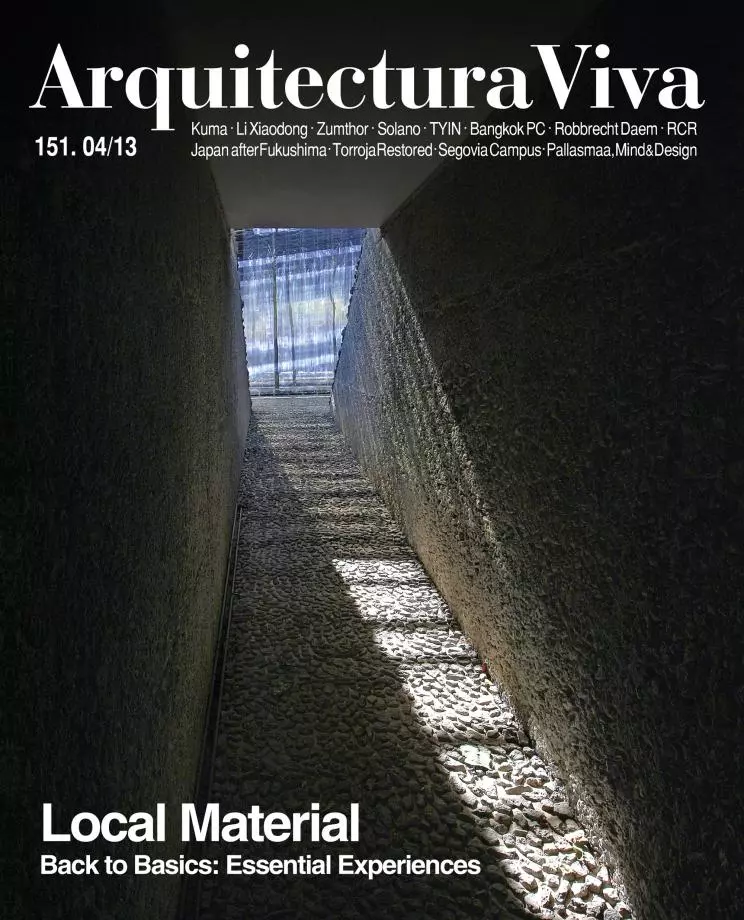

The spirituality of elementary matter and the universality of vernacular materials, which can redeem the ostentation of the unique with a laconic architectural language, is usually expressed through the silence of forms. Again in contrast with the mediatic cries that seize the whole span of attention, this architecture emits whispers, which may be almost inaudible but still stir emotions and memory. In reference to another historical setting, the French philosopher and mystic Simone Weil said that, as in swimming pools, the noise always comes from the shallow zone. And this is also the case of contemporary architecture, where the least superficial works are often the most silent.