The modem Spanish house is Spanish by need and modern by choice. Despite a heavy formal legacy, despite the material continuity of technical means and the rigorous limitations of topography and climate, the best Spanish houses refuse to limit themselves to the invariable combinations of native tradition, and pursue with the fervent of the converted the modem religion. The marks of the past, of course, are everywhere: the Roman patio or Arab brickwork, the stone constructions of the rainy north or the whitewashed prisms of the Mediterranean, the gallery or the garden wall, the labyrinth or the cistern. Nevertheless, this stubborn memory of forms acts only as a meticulous background curtain before which the will to the modern unfolds, the determination to build a new life over the tenacious fabric of what Unamuno called «the rough thickness of the race.»

The severe puritanism of the International Style, so easy to harmonize with the white and spontaneous logic of vernacular edifications in arid Spain, would have taken root in the harsh soil of the Peninsula if the catastrophes of war had not crushed the hesitant shoots of the new language, which promised to profuse in the thirties. For a definitive flourishing of modern design had to wait until the fifties, favored at that time by moderate revisions of functionalist fundamentalism. The political thaw fed the optimistic torrents of the following decade, in which organicism enriched expressive registers and lay the groundwork for professional pragmatism with a realism born at once of economic prosperity, disciplinary maturity, and the bankruptcy of stylistic dogmatism.

This impetuous stream was slowed in the seventies, detained by the ideological crisis of 68 and the economic stagnation produced by the oil crises of that decade: architectural post modernism gave form to disenchantment, legitimating memory and irony via a few polemical houses, pre-modern in their spirit and anti-modern in their rhetoric. But behind the hyperactive dynamism of the political transition, social ferment and economic reactivation gave the Spanish eighties an abundant harvest of constructions loyal to a hardened devotion for the modem. Tinged with lyrical accents, adorned with cultivated or vernacular references, and perhaps excessively bejeweled by the media’s glow, this vigorous tradition of the new extends into the present, manifesting with eloquence the persistent modern nostalgia of an architecture too often reduced to its hardy native line.

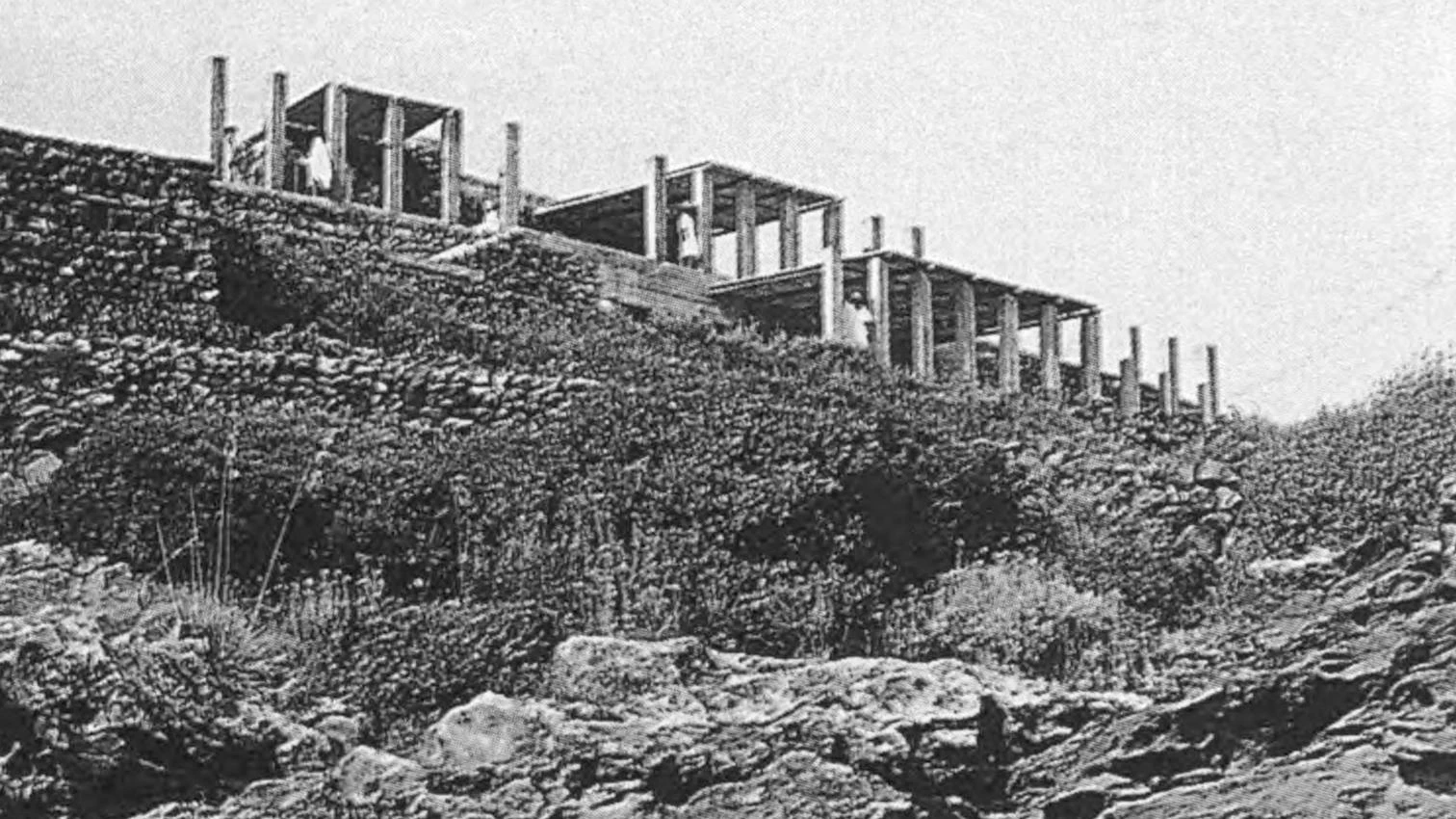

In all this process of syncopated history, houses act like sensitive seismographs, position lights and abbreviated manifestos which mark the path more brilliantly the more synthetically they tremble. There are few better examples of this laconic syncretism than the Pantelleria House, built on a small Italian island by Clotet and Tusquets in the closing years of the Franco regime. The shaded sensuality of summer hides behind the austere geometry of its porticoes, reuniting the archaic solitude of its concrete alignments with the contemporary refinement of remote leisure. Lost between Sicily and Tunisia, this Spanish house in the amiable exile of summer combines topography and memory with the modern project’s promise of liberty: small and concise, it summarizes and articulates half a century like a hinge, volcanic and distant, over whose stone leaves the wise innocence of the modern passion turns.