Looking at the past and the future at the same time, the Roman god of thresholds and transitions sums up well the profuse career of Manuel and Francisco Aires Mateus, two brothers and two studios that use geometry to take in each project a path that leads from place to life. After learning the trade at the office of Gonçalo Byrne and a period of independent professional practice, Aires Mateus acquired a voice of their own at the start of the 21st century, with a handful of works of radical composition exquisite detail, and poetic intention. These light and lyrical pieces, built essentially with geometry and light, and that address us with the synthetic force of Pessoa’s verse – As arestas fitam-me/ Sorriem realmente as paredes lisas – dazzled all those of us who follow Portuguese architecture, moving foward along the path open time ago by the master of a whole generation, Álvaro Siza.

In the latter part of their creative journey, the brothers Aires Mateus expand their formal and material repertoire, blurring the limits of the building with the exterior, the topography or the existing, crossing the frontier between silence and memory, and declining the universal language of the elements of architecture without letting this Esperanto keep them from interpreting words – as Susanne Langer proposed – in an anthropological key which lends them weight and density. This enrichment of the architectural vocabulary, which turns each new project into a discovery, and combines the heroic abstraction of their beginnings with many figurative references extracted from the historic and the vernacular, is achieved maintaining their devotion for the “lucid pleasures of thought and the secret adventures of order,” using the exact phrase of Jorge Luis Borges.

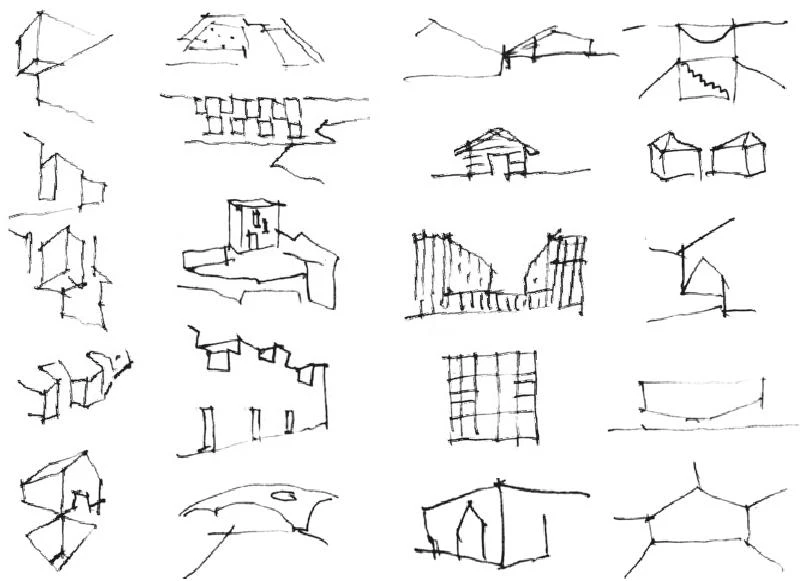

I have sketched the twenty works that follow by this two-faced studio to search for the guiding thread that ties their syncretic architecture, and the best could be the one that goes from the virginal, dematerialized, and white purity of their beginnings to the fertile and grave variety of subsequent projects, spread across a landscape of forking paths, leading to the surprise of discovery. I dare sum up that tension with the last two lines of two Iberian poets, both disappeared just a few years apart. When Antonio Machado died in Colliure, a crumpled piece of paper found in the pocket of his coat read, “estos días azules y este sol de la infancia;” and the day before his death in Lisbon, Fernando Pessoa wrote “I know not what tomorrow will bring” in pencil on copy paper. Perhaps the oeuvre of this geometrical Janus moves between the blue days of yesterday and the stubborn uncertainty of tomorrow.