Perhaps like us, buildings live in time and perish in space. They are built over years or decades and often last centuries, suffering the ravages of weather, use or conflict, experimenting metamorphoses or changes and in the end being demolished or crumbling down on their sites, leaving behind their memory in images and their traces on the ground. These palimpsests of constructions and stories is what we call heritage, and dealing with it is always an ideological and aesthetic minefield. The modern cult of monuments, as Alois Riegl named it in 1903, has become a religion with priests and sacred texts, blending historic and artistic values with those of antiquity or memorial character, and the traditional division between the restoration to origin of Viollet-le-Duc and the dignified aging of Ruskin no longer opposes white cathedrals and ruins, but artificial extension of life and euthanasia.

Arquitectura Viva has dealt monographically with heritage on several occasions, but more often over this last period. After the two issues of 1993, ‘Hacer memoria’ (32) and ‘Monumento nuevo’ (33), we did not pick up the subject again until 2006 with ‘Pasado presente’ (110). Since 2010 with ‘Patrimonio Nacional’ (131) the pace quickened, and the magazine presented its first bilingual issue in 2013 with ‘Transformations’ (148), followed in 2014 by ‘Palimpsests’ (162); in 2015 ‘Second Life’ (171) and ‘Homegrafts’ (176); and in this year 2016 ‘Industrial Heritage’ (182). The articles and projects published in them offer a source of information and ideas, but regardless of how they might be judged, if magazines are at least opinion seismographs, there are few doubts about the growing importance of heritage issues, if gauged by the frequency and intensity of the tremor of needles.

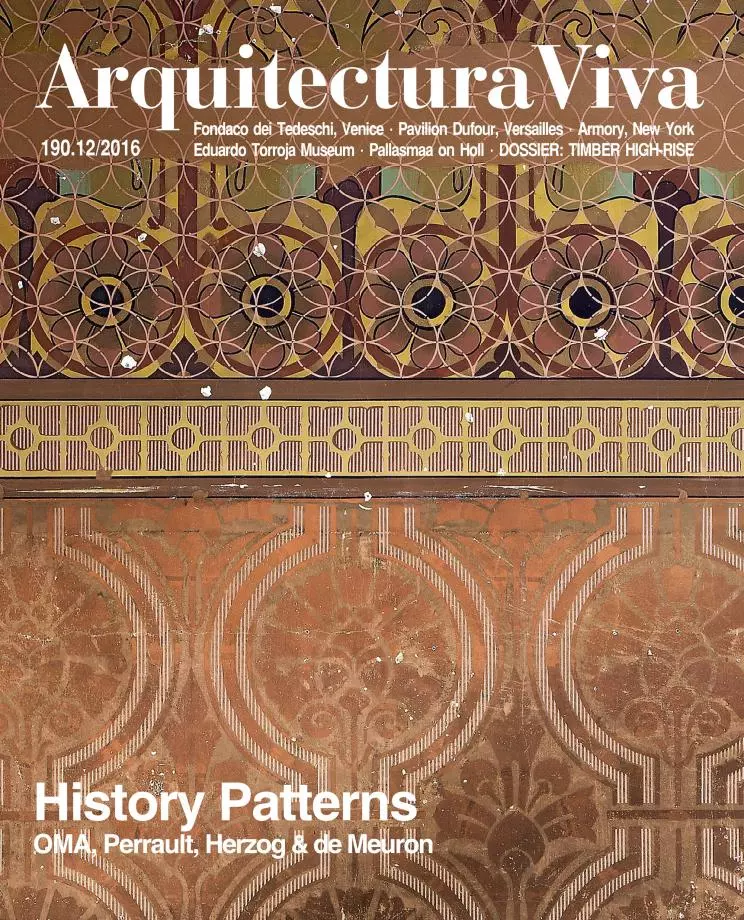

If Riegl opened our eyes to the formal richness that can be found in late antiquity, perhaps we should explore the excellence that our late modernity treasures. Here we have selected three works by three European offices in Venice, Versailles and New York, that resort to different patterns of intervention in heritage, writing a new chapter in the living history of the respective buildings. And if this architecture is always, as I once wrote, ‘a history of violence,’ because building on the already built entails a surgical operation on the existing, we can also give special value to those projects that undertake the transformation of heritage with the sensitivity of those who do not want to leave an aggressive trace of their passing, moving in the imprecise ground that separates the inmutability