From the classical Grand Tour to the contemporary road movie, the journey has always been a route of discovery. Be it a study tour or a random wandering on wheels or rails, moving to other physical, social and cultural geographies is both an educational experience and a common rite of passage. Jingoism and prejudice are cured by travel, and there is no better stimulus for thought and emotion than the free circulation of bodies and minds. Advisable for anyone, travel is essential for architects, because the experience of buildings is hardly conveyed through photographs or drawings: only the actual visit permits to fully understand a structure, not to say a city or a landscape. The journeys of architects, from Soane or Viollet-le-Duc to Le Corbusier or Kahn, are an artistic and literary genre, but also a rich and fertile legacy.

The eclosion of mass tourism in the second half of the 20th century has given travel a different meaning, because it is not easy to establish a thread of continuity between the gentleman in search of antiquities or the bourgeois of the Wagons-Lits and Baedecker guide with the young of the crazy techno afternoons in Ibiza. This massive travelling, spurred by the automobile first, and later multiplied by cheap flights, has in any case eroded frontiers of ignorance and mistrust, and has spread behaviors and customs, promoting tolerance and acceptance of diversity. Product of the postwar social pact, which generalized paid vacations, the industry of leisure has often been viewed with elitist disdain, but for most of the population, tied to a routine, sterile job, it has been a source of pleasure and a compensatory mechanism.

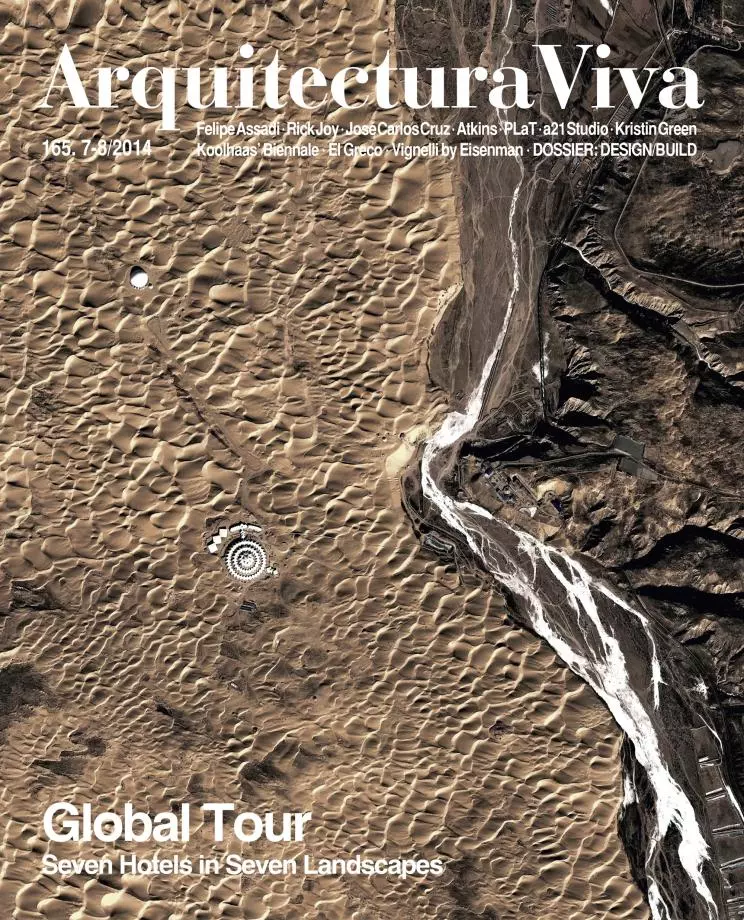

In this global entertainment business, architecture has played a prominent role, producing icons whose Michelin stars provide the city branding that attracts visitors, with theme parks that concentrate the world’s most emblematic buildings for rushed travellers, or through exotic hotels where guests are treated to adulterated or genuine experiences. No one has explored contemporary tourism, from organized travel to holiday clubs, more lucidly than the writer Michel Houellebecq, with a desolate and tender gaze where the emotional devastation of men and women is suddenly lit up by the promise of happiness offered by a time frozen in a distant place. As he claims in his story Lanzarote, “the world is medium sized,” and those of us who can reach its most remote landscapes probably are too.