What is Bothering Me?

The launching in Madrid of the Hotel Puerta América, designed by 18 world firms, sets a bittersweet milestone in the use of architectural stars as marketing props.

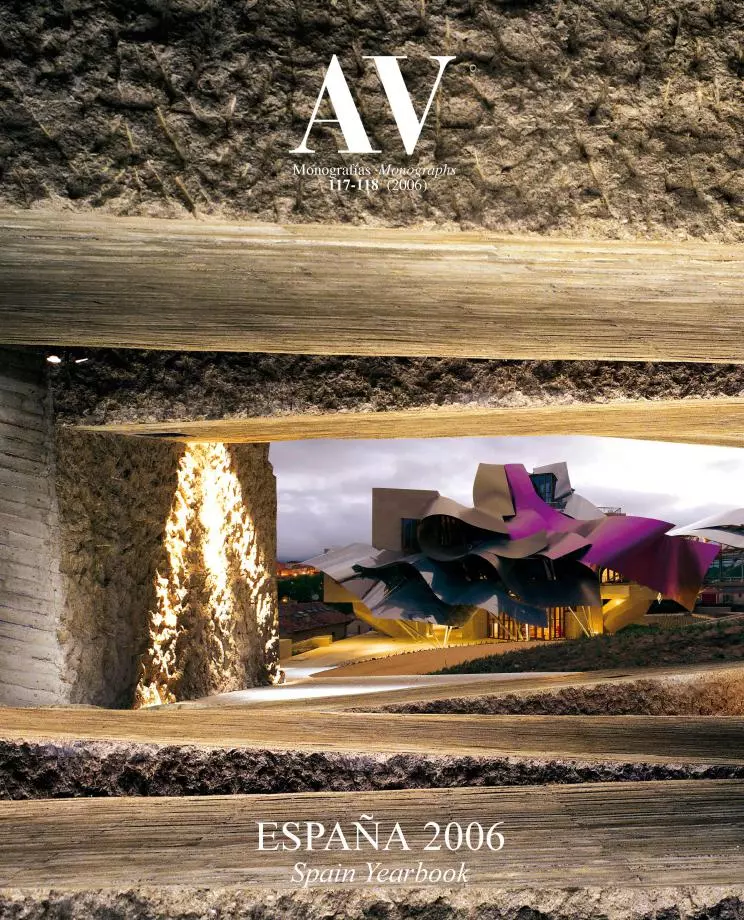

It will be a good thing, I am told at the newspaper, to do something on the Puerta América, a Madrid hotel that has commissioned the decoration of each of its floors to a different architect, and that was presented to the public on 19 January with much media hype. Situated on the Avenida de América, beside Sáenz de Oíza’s Torres Blancas apartments, it is still unfinished. The early launching has essentially been a marketing operation, one meant to maximize returns on the intervention, in its design, of a well-nourished group of international stars, who took part in the presentation by explaining their intentions. Never mind the architecture of such insufferable triviality – a core of elevators joining two 12-story wings with rooms on both sides of the corridors – that Jean Nouvel hardly manages to dissimulate through a lining of colored canopies with poetic phrases that looks like a kindergarten mural. And never mind the hilariously pompous statements of the developers, a hotel chain claiming to have conceived its flagship as “a cultural manifesto where different cultures, creeds, and races are present.” The fame of the personalities involved has ensured the project extraordinary coverage. (This newspaper alone featured it in its culture section in a whole page titled “A Hotel by 18 Stars”; in its real estate section under “A Crazy Hotel,” where it was profusely illustrated; and in its travel section under “At the Hotel with Foster and Zaha Hadid,” naming the two Pritzkers of the so-called dream team who, incidentally, did not turn up in the promotional event). There is indeed no doubt about the subject’s journalistic pull. What is it, then, that is bothering me?

The launching in Madrid of the Hotel Puerta América, designed by 18 world firms, sets a bittersweet milestone in the use of architectural stars as marketing props.

Mayor Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón appeared declaring his support in a project that reflects “what Madrid is and wants to be,” rejoicing in the city’s being a “capital of world architecture” and praising both the diversity of the participants and the entrepreneurial excellence of an initiative that, through an investment of 75 million euros, will add 342 rooms to the Spanish capital’s hotel capacity, a factor to be considered by the International Olympic Committee when it decides on the venue of the 2012 Games. Of course the heterogeneity of the interior design offers a thematization of floors – quite like those vacation hotels where one can go for the Versailles suite or the Texan ranch, the Polynesian hut or the Tirolese cottage – that singularizes the installation in our supply-side economics. The orange canopies on the edge of the highway that connects Barajas Airport to the city center will mark “the hotel of the architects”, a place that will, moreover, require multiple views for the experience to be complete, as in “I still have to try the Zaha floor.” (In his memoirs, referring to offices, the recently remarried developer Donald Trump convincingly explained the advantages of notoriety, and how fashionable buildings designed by fashionable architects were rented out sooner.) On the other hand the hotel business is essentially a real estate business, and if you think about it, so is an Olympic bid. There is a clear synergy between the project and Madrid’s vying to host the Olympic Games that endorses its being of political interest. What then, again, is bothering me?

The new Madrid hotel, wrapped by Nouvel with colored canopies which carry poetry lines about freedom in different languages, goes up on the avenue that connects the city with the airport, next to Oíza’s Torres Blancas.

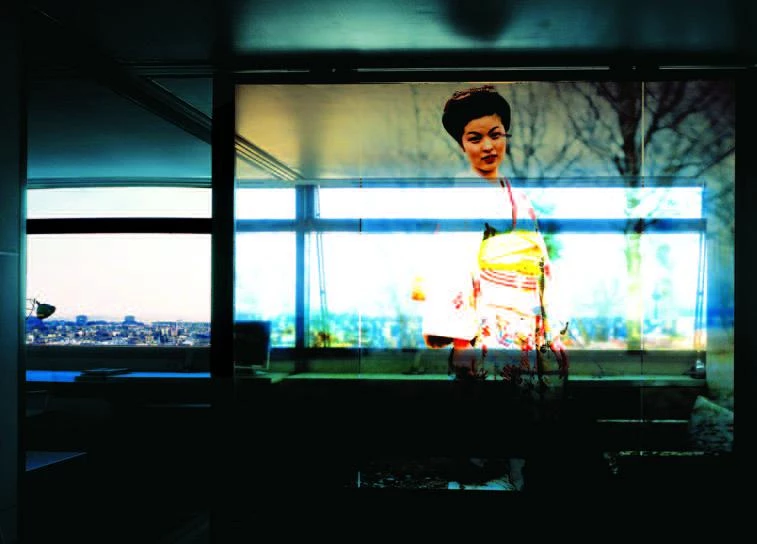

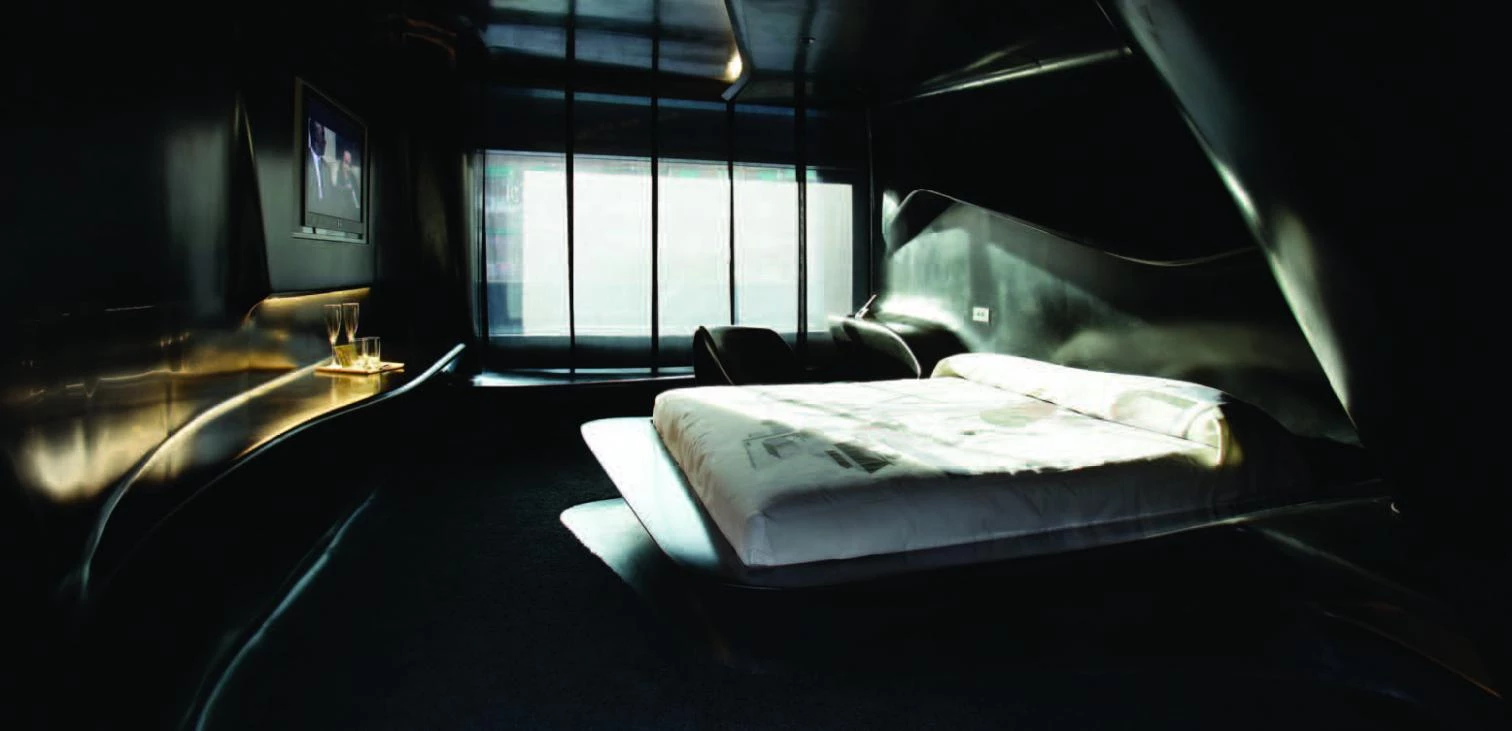

Hotel-museum and museum-hotel were the hyperboles used in ARCO director Rosina Gómez-Baeza’s presentation to describe what to her is a “crucible of cultures and a symbol of creative freedom.” In this club sandwich of signature interior decoration there is not much room for fusion or mixture, so metaphors of the crucible-cocktail family seem inappropriate. Another matter is the creative freedom of the tasting menu or the cheese assortment tray, though presented here in the confectioner’s variety of a multi-tiered cake or puff pastry. Freedom is, in effect, the key word of the project, and multilingual fragments of Paul Éluard’s “Liberté” appear on the canopies in schoolchild’s handwriting so that no guest misses the motto of the operation. Never mind that the 1942 poem was a political text thrown from the air over occupied France, one whose rote-facilitating psalm structure was meant to make it an instrument of emotional mobilization in the anti-fascist struggle. Here it is with frivolous prestidigitation transmuted into an emblem of artistic freedom in its most banal sense, the absence of rules and picturesque extravagance. Nouvel stretches the libertarian discourse to the sexual field, claiming to have been inspired by “The Naked Maja” in the creation of scenes of “licentiousness,” in the same way that his colleague Kathryn Findlay assures us that her designs stimulate “rest and orgasm.” Whether a hotel-museum, as the director of ARCO would have it, or a partouze like those described by Catherine Millet, this orgiastic babel of stars of architecture and fashion is of glaring artistic interest. What, in the end, is bothering me?

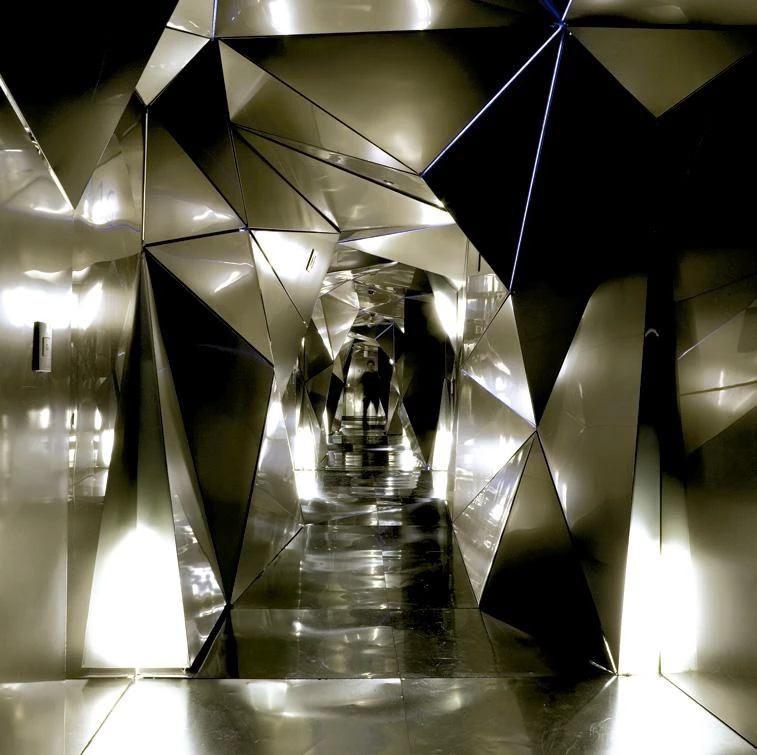

In the end, what’s important is not so much the journalistic, political, or artistic guarantee as the indisputable fact that a handful of architects of consolidated talent lends itself to participate in a project of this nature. It doesn’t do to call it just another job, presumably a well-paid one – although fees have for confidentiality reasons not been revealed – and leading to other commissions – Foster has announced that the same chain has assigned him to build a hotel in London, and surely there are more such commitments –. Without a doubt the problem is not one of interior design, which is simply a way of practicing architecture that many of the participants have successfully subscribed to at some time or another. Neither is it a problem of ‘exteriorism’ – the term Frank Lloyd Wright used to revile Richardson –, entrusted here to Nouvel, in his capacity as specialist in carrosseries et capots besides author of excellent hotels, and it is a field that Albert Viaplana, for example, practiced to no reproach in the Hilton of Barcelona’s Diagonal. Neither can we attribute the bad feeling to the general subject of hotel design, because while it tends toward disconnected fantasy of the Morris Lapidus or Disney kind, it has in fact yielded works of exemplary rigor like Arne Jacobsen’s SAS or typologically innovative buildings like John Portman’s atrium-hotels, not to mention refined interiors like Andrée Putnam’s or Philippe Starck’s for Ian Schrager, who, incidentally, also entrusted a finally unexecuted project to Rem Koolhaas in conjunction with Herzog & de Meuron. If I am feeling bad, it is for other reasons.

I do not find it in me to accept that the author of the Millau viaduct, a masterwork of engineering and a new symbol of France, should busy himself with the second floor of a techno-seedy construction. I would rather not know that the author of Berlin’s Museumsinsel project, a sophisticated assemblage of historical architectures and laconic contemporary pieces, is participating in this rushed promotional parade. I cannot agree with the author of the monastery of Novy Dvur in the Czech Republic, a polished exercise in enlargement that competes with the Cistercian work in austerity, needing to take part in this motley party of designers and couturiers. And beyond the British trio of Foster, Chipperfield and Pawson, perhaps nothing irritates me more than the childish use of Paul Éluard’s heroic anaphora at the service of petty advertising. Whoever it is whose idea this was ought to be asked the question fired to McCarthy: have you left no sense of decency?

The interior design of the hotel has been assigned to an impressive group of international stars, who have taken care of both the common areas and the rooms, along with the access corridors in each of the different floors.

Indeed, the Pritzker family awards its prize without significantly improving architectural quality in the hotel chain it owns, and it is no less true that architects have openly joined the fame game of luxury and fashion. Neither the hotelier-patrons nor the architect-stars are exempt from reproach in the tango of publicity and design that has acted out its latest episode in Madrid. But those of us who write in newspapers would do well to listen to the words of the Ombudswoman of El País, who in view of the media’s increasing loss of credibility suggests we follow the advice of an editor of The Washington Post: “Let’s go back to writing on injustices and insults, to telling what the authorities don’t want known… let’s recover the taste for good writing and refuse to fill newspapers with press conferences.” So be it.