Europeans vaunt about their tenacious experimental tradition in the field of housing, but a distracted review of the latest residential projects leaves a bittersweet aftertaste. Apart from some odd technical displays and a few typological novelties, the majority of the projects presented in this issue stand out for their geometric rigor, their material sophistication and their compositional elegance. Rather than a product of the Welfare State, they are a consequence of the welfare of the State – promoter of a large number of them – and also of the social prosperity made evident by the boom of private real-estate development. Examples of the refinement of the European elites, these works also bear witness to the creative fatigue of a continent that finds itself demographically aged, economically less and less competitive, and with a knowledge industry that continues to lag behind the universities and laboratories of the American north, and now also in comparison with the dynamic surge of Asia.

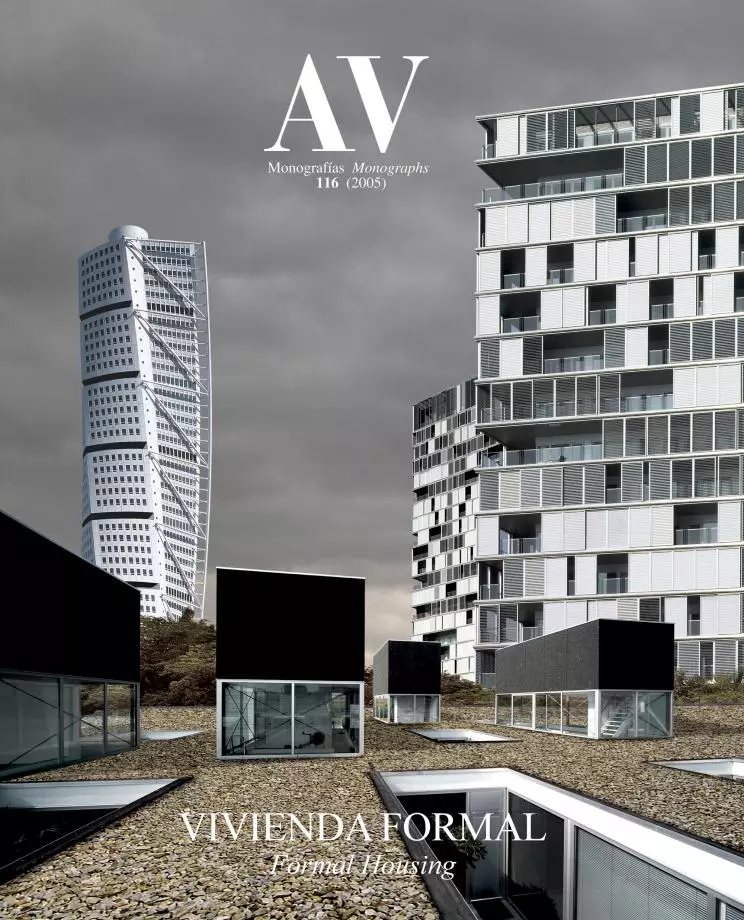

Be it the new residential towers that go up in the fragmented edges of the urban continuum, the housing complexes that serve to complete, stitch or revitalize that fabric, the volumetric variety of the blocks located in singular environments, or the assemblages of houses that give the peripheries a certain urbanity, these different ways of living in the European city share an essentially aesthetic understanding of the construction of the environment, as is perhaps inevitable in a continent as opulent as our own. Always excellent pieces from an artistic and formal point of view, but seldom provocative proposals from a sociological and political perspective, these projects testify to the contemporary imbalance between the quality of architecture and the uncertainty of urbanism, which turns these bijoux indiscrets into an uncomfortable reminder of the times, not yet so distant, in which housing and city were considered inseparable matters in research and practice.

Though it is true that European architecture is now experiencing wide recognition, and that its average level is above American or Asian standards, this bold assertion is only valid from an abridged perception of the purposes and boundaries of architecture, a narrow conception that reduces it to the creation of exquisite objects. Understood in somewhat more generous terms, architecture incorporates as much the technological inventiveness and skill in distribution that characterizes the American context as the social choreographies and effectiveness in production that are distinctive features of the Asian model, and both pairs of coordinates converge in the projects that close the issue, where the construction with components is placed at the service of the suburbanization of Texas and California, and where the versatile exactness of the mixed-use programs orchestrates the hyperurban density of Tokyo: two extreme examples that perhaps contain a useful lesson for this equidistant and exhausted Europe.