Three months before turning a hundred, Françoise Choay died on 8 January, and her intellectual legacy makes it inexcusable not to publish an obituary, no matter the delay. The French historian, who situated the origin of architectural theory in Leon Battista Alberti and that of urban planning in Ildefons Cerdà, devoted her mature work to built heritage, defending it with erudition and critical intelligence in the face of those who understood it in an exclusively mercantile way, or sought to freeze the history deposited in buildings to transform them into tourist sites.

Choay, to whom we owe those extraordinary contributions to the theory of architecture and urbanism, from her germinal La Règle et le Modèle (1980) to the later critical editions of Haussmann and Alberti, made heritage the object of much of her intellectual energy in the last decades of her life. Fruits of this were L’Allégorie du patrimoine (1992), Pour une anthropologie de l’espace (2006), and Le Patrimoine en questions (2009), an anthology of historical texts (from Abbot Suger in the 12th century to a 2008 UNESCO document), preceded by a detailed introduction, which she conceived as a tool for curbing the trends generated by globalization that turned our built heritage into merchandise or museum.

Inspired by the anthropological intuitions of Claude Lévi-Strauss and nourished by his exceptional erudition, Choay extended Alois Riegl’s analyses on the substantive difference between the monument as a depository of memory (and here we must remember the death on 2 June, at 93, of Pierre Nora, the historian who coined the concept of lieux de memoire) and the historical monument as an object of intellectual and artistic value, an exclusively Western invention forged in the cultural revolution of the Renaissance and crystallized in the Industrial Revolution of machinism; illustrated the importance of the daguerreotype and photography in the creation of an imaginary museum of architecture and historical monuments, propelled by tourist guidebooks and early architecture magazines; and explored in detail the conventional opposition between Ruskin’s British conservatism and Viollet-le-Duc’s French progressivism, explaining that both authors were part of Western European culture.

In the final analysis, what most preoccupied the French emeritus professor was what she called ‘electro-telematic revolution,’ with the rise of the virtual to the detriment of the body’s physical relation to the world; the use of ever more sophisticated prostheses, materializing Freud’s predictions on transforming man into a ‘prosthetic God’; the weakening of institutions to the benefit of a pseudo-free individual; the rupture of living memory in favor of the instantaneous; and the normalization of cultures through the effacement of their differences.

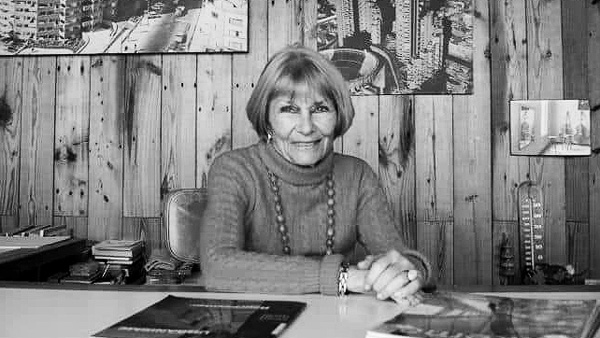

An attentive reader of La Règle et le Modèle, I met her in Seville in 1988, in the context of meetings prior to Expo 92. She liked what I had published in AV on ‘Architecture, Body, and Language,’ and that same year invited me to join her seminar on those subjects at Université Paris-VIII. I interviewed her in 1989 for an Arquitectura Viva issue on her city, and in the following years she wrote on urban and heritage matters for the magazine, and we reviewed her books and included her in the selection for ‘Doscientos’ (2017) and Maestros de escritura (2021).

A grand dame of erudition and criticism, Choay brilliantly explained to us that, as in the living languages to which she devoted her lexicographic studies, preservation and demolition coexist in material constructions, because for life to evolve, the archaic and the disused have to be eliminated: a controversial posture she defended with the passion and the consistency that always characterized her work.

L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui: Françoise Choay, 1925-2025