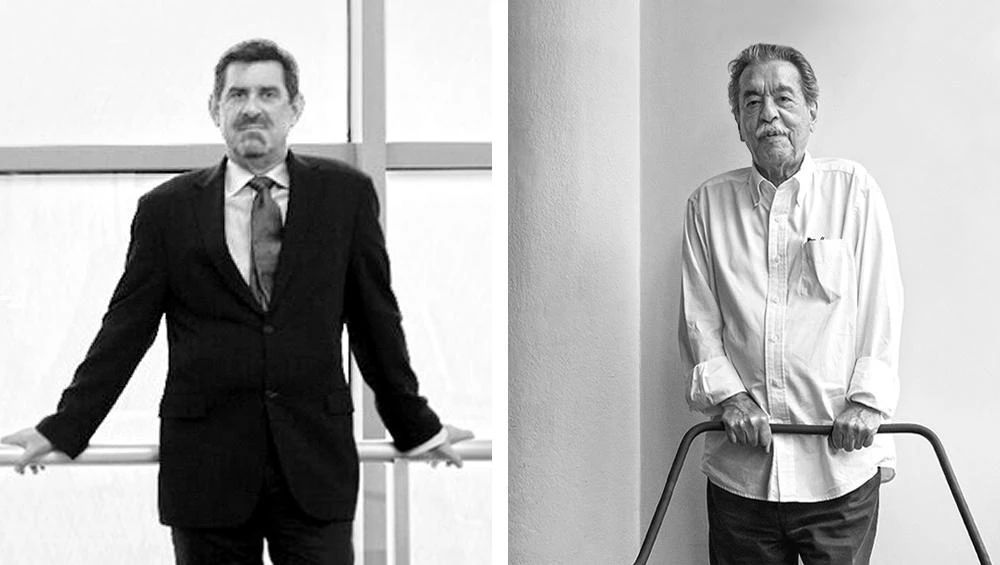

A single week in May has taken away two American friends: Terence Riley at 66 on Monday the 17th, and Paulo Mendes da Rocha at 92 on Sunday the 23rd. Our paths crossed fifteen years ago, with one and the other, and now we bid them farewell at the same time. The American then headed the MoMA’s architecture department and came to Spain several times to visit the works he would include in ‘On-Site: New Architecture in Spain,’ a major exhibition – the first one done on a single country by the New York museum since the mythical ‘Brazil Builds’ of 1943 – that opened on 12 February 2006. Two months later, on 10 April, came the announcement of the Pritzer Prize for the Brazilian, and that day I devoted a page to him in the newspaper El País, to later attend the ceremony that brought all three of us together, on 30 May, at the Dolmabahçe Palace in Istanbul, on the edge of the Bosphorus, in the presence of then Prime Minister Erdogan, who in his tribute to the Paulista architect stressed Turkey’s commitment to open up, an endeavor perhaps akin to Spain’s own, which had led us to enjoy being showcased that same spring on 53rd Street.

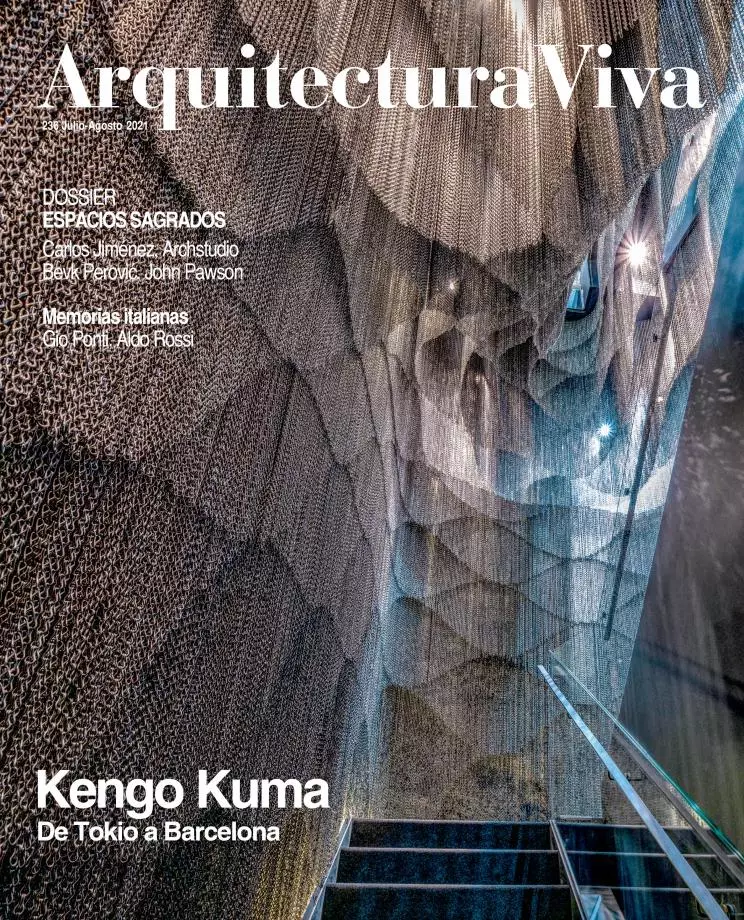

A graduate of Notre Dame and Columbia, Terry Riley – having in 1991 been chosen by Philip Johnson to pilot the department he had created at the museum – had curated exhibitions as celebrated as the ones on Frank Lloyd Wright or Mies van der Rohe, and as influential as ‘Light Construction’ in 1995 or ‘The Un-Private House’ in 1999, but perhaps none as far-reaching as the part he played in overseeing and selecting an architect for the enlargement of the building, ultimately entrusted to the Japanese Yoshio Taniguchi and inaugurated in 2004. It was in the redesigned museum that the Spanish exhibition was held, accompanied by two publications, the catalog presenting the projects on display, which I had the honor of prefacing, and Spain Builds, the book produced by Arquitectura Viva (with background from 1975 on), this time with a foreword by Terry, who, incidentally, would immediately afterwards leave the MoMA for Pérez Art Museum Miami, where he again combined exhibition curating with raising a new building, for which he chose Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron. Although he brought with him to Florida the architecture practice he had since 1984 shared with John Keenan, and worked from there with the developer Craig Robins on projects for a city energized by the launch of Art Basel Miami, perhaps no legacy of his is as imperishable as the two museum buildings I cannot imagine without his participation, the MoMA of Taniguchi and the PAMM of Herzog & de Meuron.

‘Brazil Builds’ was curated by Philip Goodwin, a Beaux-Arts architect and MoMA trustee who in 1939, with the more avant-garde Edward Durell Stone, had completed the museum’s first renovation, and who in the summer of 1942 had combed the country with a photographer to document a historical fresco stretching from colonial architecture to the henceforth iconic tropical modernity of Oscar Niemeyer. Goodwin highlighted the brise-soleil, slanting pillars, and fluid forms of the Carioca works, but missed the other great crucible of Brazilian architecture, the Paulista School, which came later, championed by João Vilanova Artigas, author of the Faculty of Architecture and Urban Planning, and subsequently by Paulo Mendes da Rocha. The latter was two decades Niemeyer’s junior and closer than him to the structural expressionism of huge concrete spans, as is evident, for example, in his admirable Brazilian Museum of Sculpture, a 60-meter concrete slab that covers a public square. The Pritzker awarded in Istanbul – 18 years after it went to Niemeyer, and with him to the curves of Carioca Corbusianism – honored an individual career, but also a collective undertaking, as Paulo noted in his acceptance speech, and as he would reminisce years later during the conversations we held in his São Paulo studio which would then yield an AV monograph in 2013.

In this cérémonie des adieux I wish not to evoke the harassed and ironic Terry of New York lunches, but the one who crossed Spain in GPS-less rental cars that did not make it easy for him to reach the architectural destinations in the territories of our pentagonal peninsula, and who would summon me to the Hotel Palace lobby, under the rotunda skylight, for a sharing of confidences on like-minded friends and less good words on rhetorical and vacuous figures; and I do not wish to remember the Paulo in tuxedo at the Ottoman palace, but the one who would tell me of his difficulties while handling tiny models in his modest and bare office in São Paulo, stressing his stubborn commitment to civic and community values; a commitment, to be sure, shared by an entire generation of Brazilian architects, Paulista and Carioca alike. The much too early demise of Terry and the chronologically more expected death of Paulo make the world of architecture smaller, and all of us more aware of the fragility of life and the inevitable finitude of our works and days.