Sacred Spaces Today

Marina Tabassum, Mezquita Bait Ur Rouf, Daca (Bangladés)

ARCHITECTURE in capital letters, architecture conceived to last long, was mostly sacred architecture. The origins of the discipline are confused with religious rituals. In fact, the first architect of history, Imhotep – who built the pyramid of Saqqara in Ancient Egypt – was also and above all a high priest. Every civilization, every generation, has expressed its yearning for transcendence by erecting grand buildings.

From the tombs of the pharaohs to the Parthenon, from Buddhist stupas to Mayan pyramids, from Shinto gardens to Gothic cathedrals, the rosary of temples dotting the story of human civilization is as long as civilization itself. With the onset of secularism, however, the beads that could be strung onto that tradition began to be scarce, becoming altogether rare. The age of the machine was not at all an age for faith to thrive in, and avant-garde architects busied themselves with other matters and problems. The outcome was a paradox: religious architecture, formerly in the best hands and frequently a laboratory for innovation, became a haven for a conservatism that soon meant mediocrity.

The West had to wait for the dynamic times of the Second Vatican Council – which not entirely coincidentally concurred with the critical revision of modernity – to see the winds of reform reach ecclesiastical architecture, and the finest architects once again involved in designing spiritual spaces. Le Corbusier in France, Gottfried Böhm in Germany, Sigurd Lewerentz in Sweden, Pier Luigi Nervi in Italy, and Miguel Fisac in Spain are just some of those who knew to break past old typologies and propose models endowed with unprecedented spatial breadth and material quality; models where the historicist codes that were until then de rigueur, combined with the ornamentation attached to liturgical tradition, gave way to a language in line with modernity, a language in which bare did not mean un-sublime.

It is under this modern tradition, precisely, that we must situate the projects which today are giving religious architecture an overhaul, as much in spatial and material terms as in the attention given to the requirements of creeds that, by the way, are no longer just the Christian ones but also the other great religions and even the faith, paradoxically, of lay transcendence.

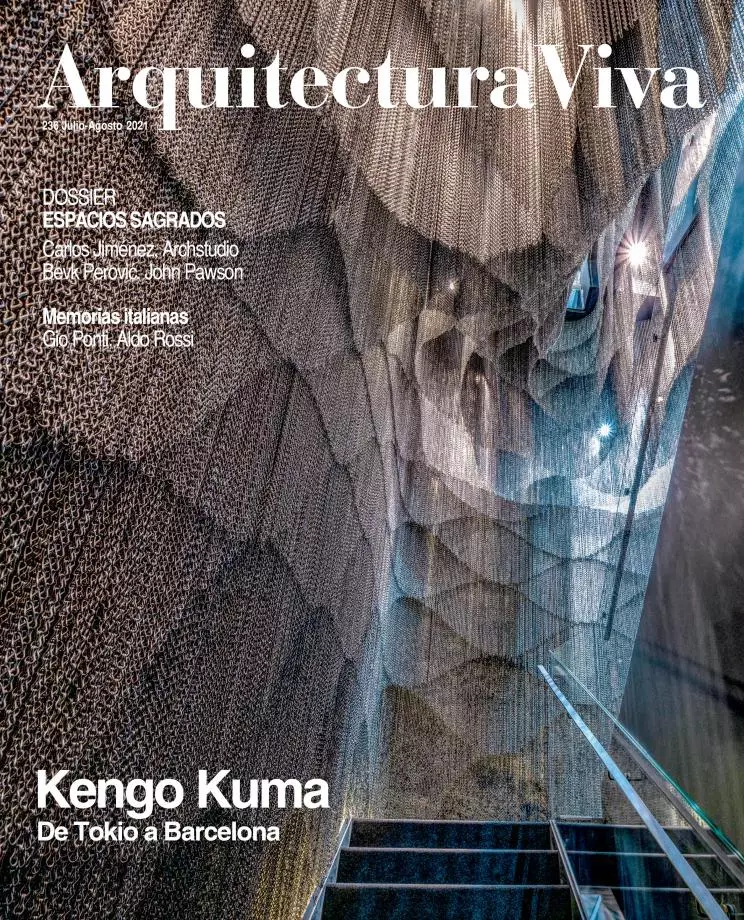

The variety is illustrated by the four works selected for this dossier: Carlos Jiménez’s essential and domestic Won Buddhism Temple in Houston;

Archstudio’s telluric and haptic Buddhist Shrine in Tangshan (China); Bevk Perović’s at once Cartesian and metaphysical Islamic Religious and Cultural Center in Ljubljana (Slovenia); and John Pawson’s Wooden Chapel in Unterliezheim (Germany), which is totemic in its radical way of inserting itself into the landscape, and atmospheric in its intimacy and openness to climate phenomena.

Eduardo Souto de Moura, Capilla del Vaticano para la Bienal de Arquitectura, Venecia (Italia)