In Praise of Calmness

The photo by Paul Hester of the interior of Carlos Jiménez’s Red Studio of 1983 neatly summarizes Jiménez’s architecture of the last thirty years. As the projects in this monograph demonstrate, the square plane, the rising diagonal, volumetric recession (both shallow and deep), and the application of color are the building blocks of Jiménez’s architectural imaginary. For more than three decades, he has explored the potential that these affects possess to construct spatial experiences. Additionally, Hester’s photo documents a spatial condition that no longer exists since Jiménez’s reconfigurations of his workspace have altered the original. In this respect the photo surreptitiously introduces the factors of time and change to consideration of Jiménez’s architecture.

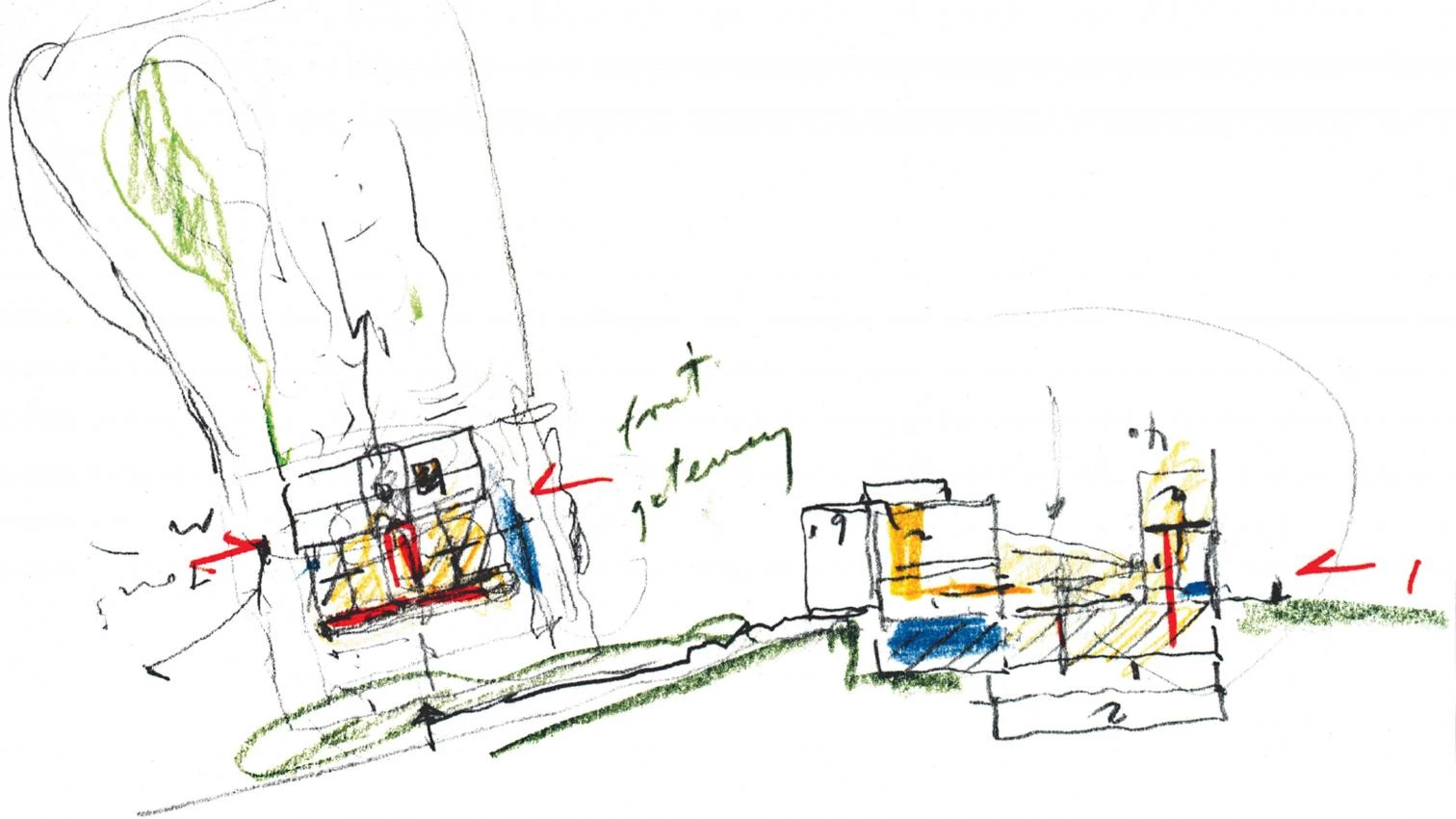

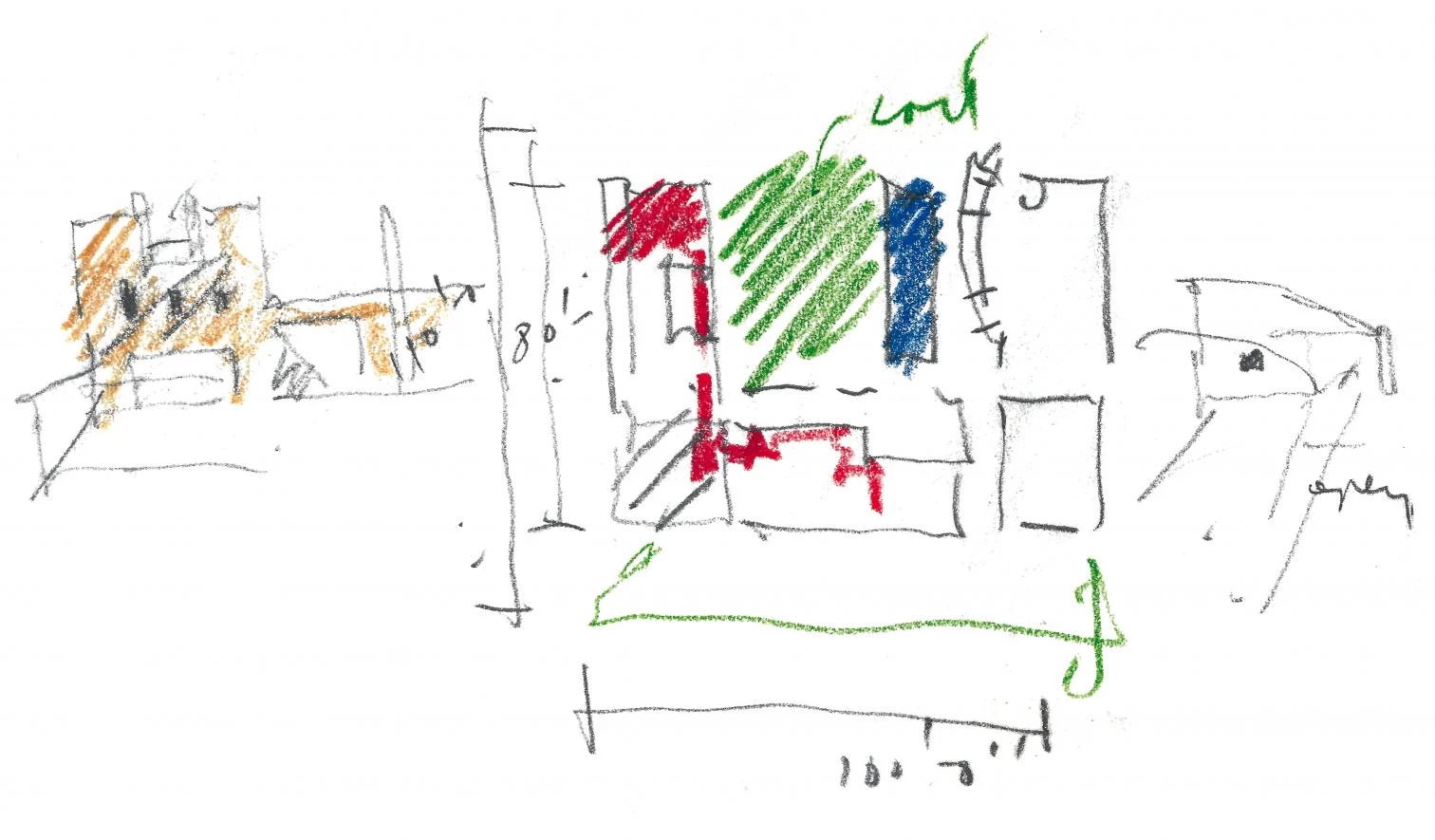

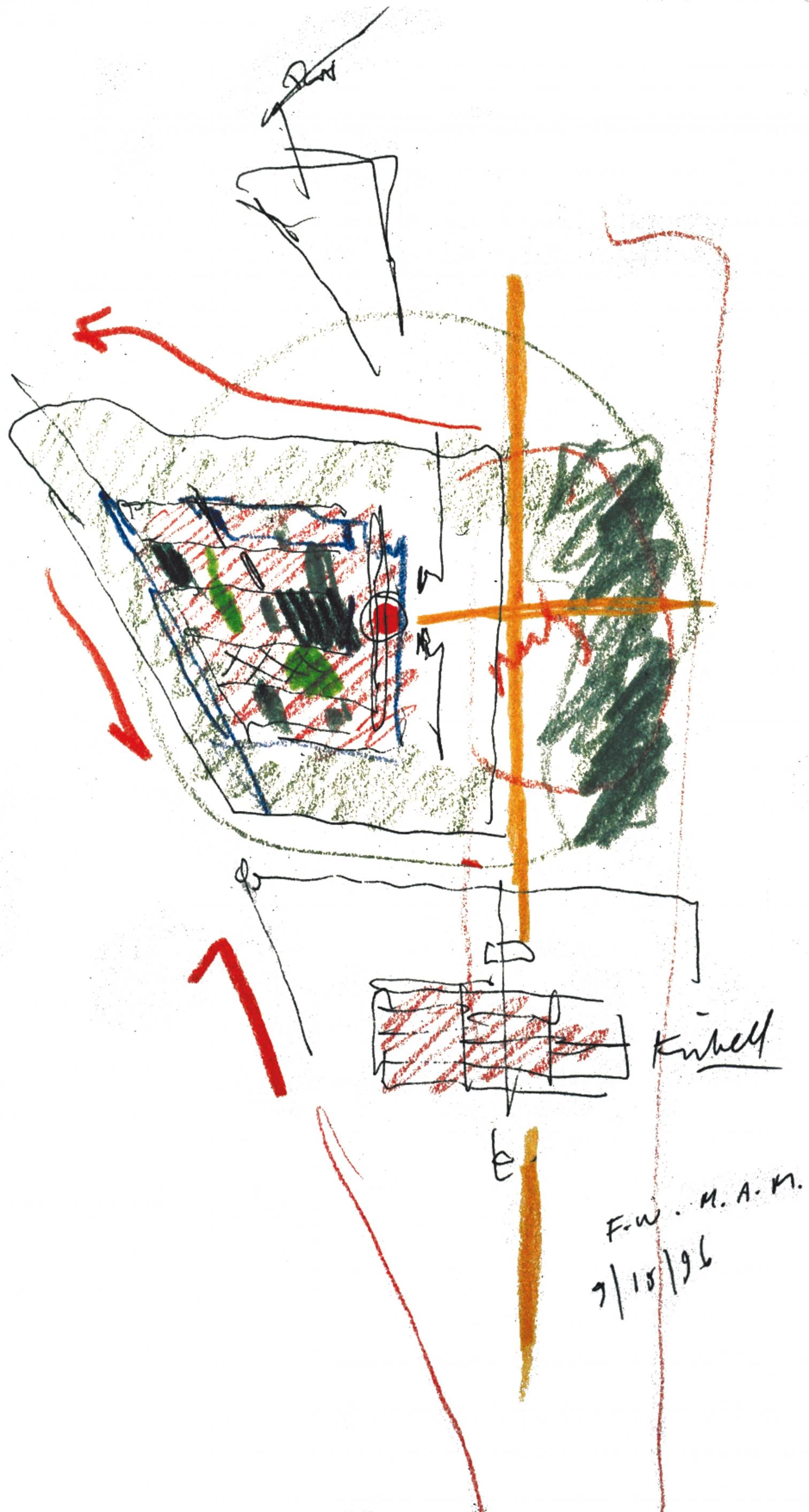

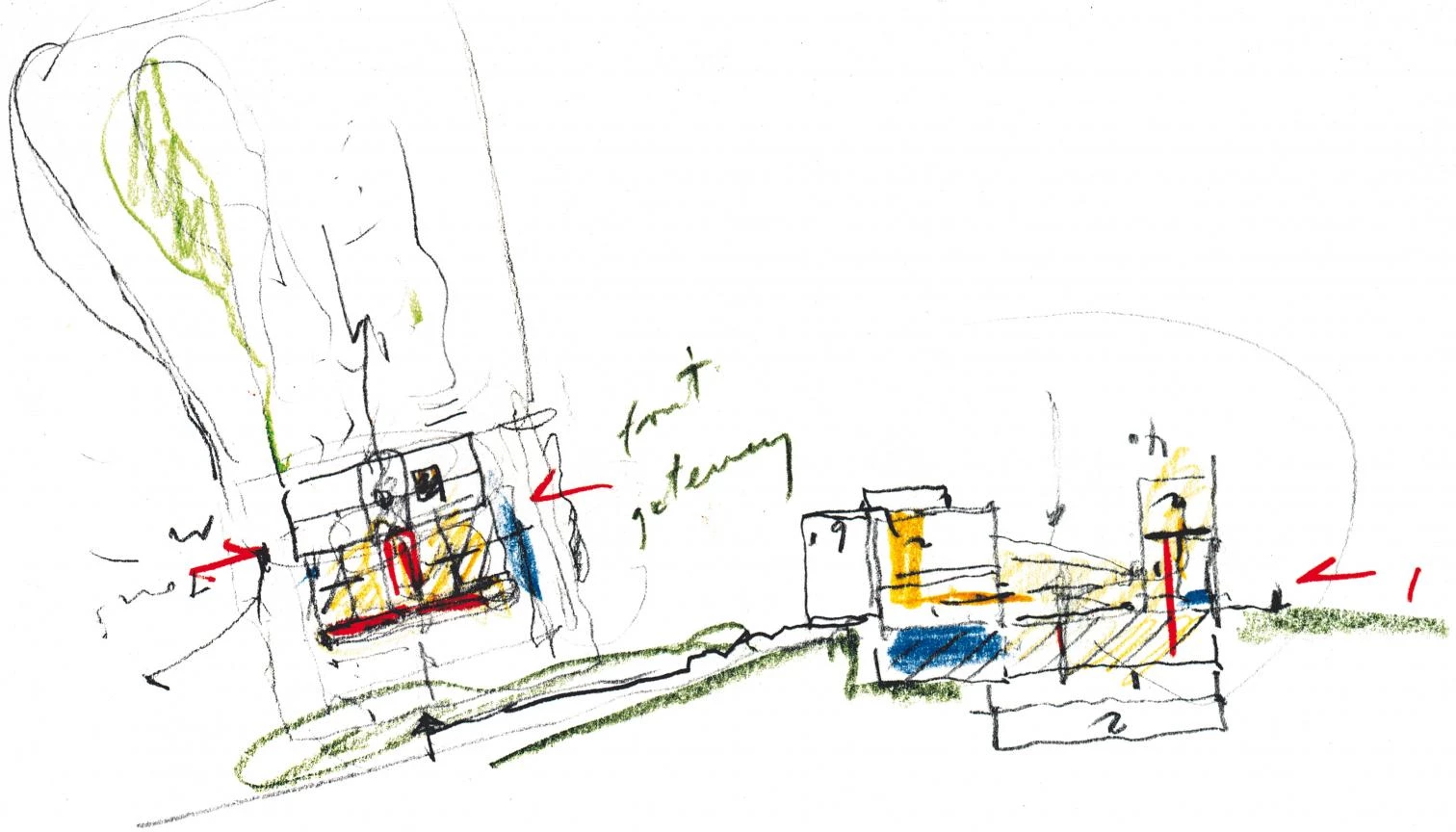

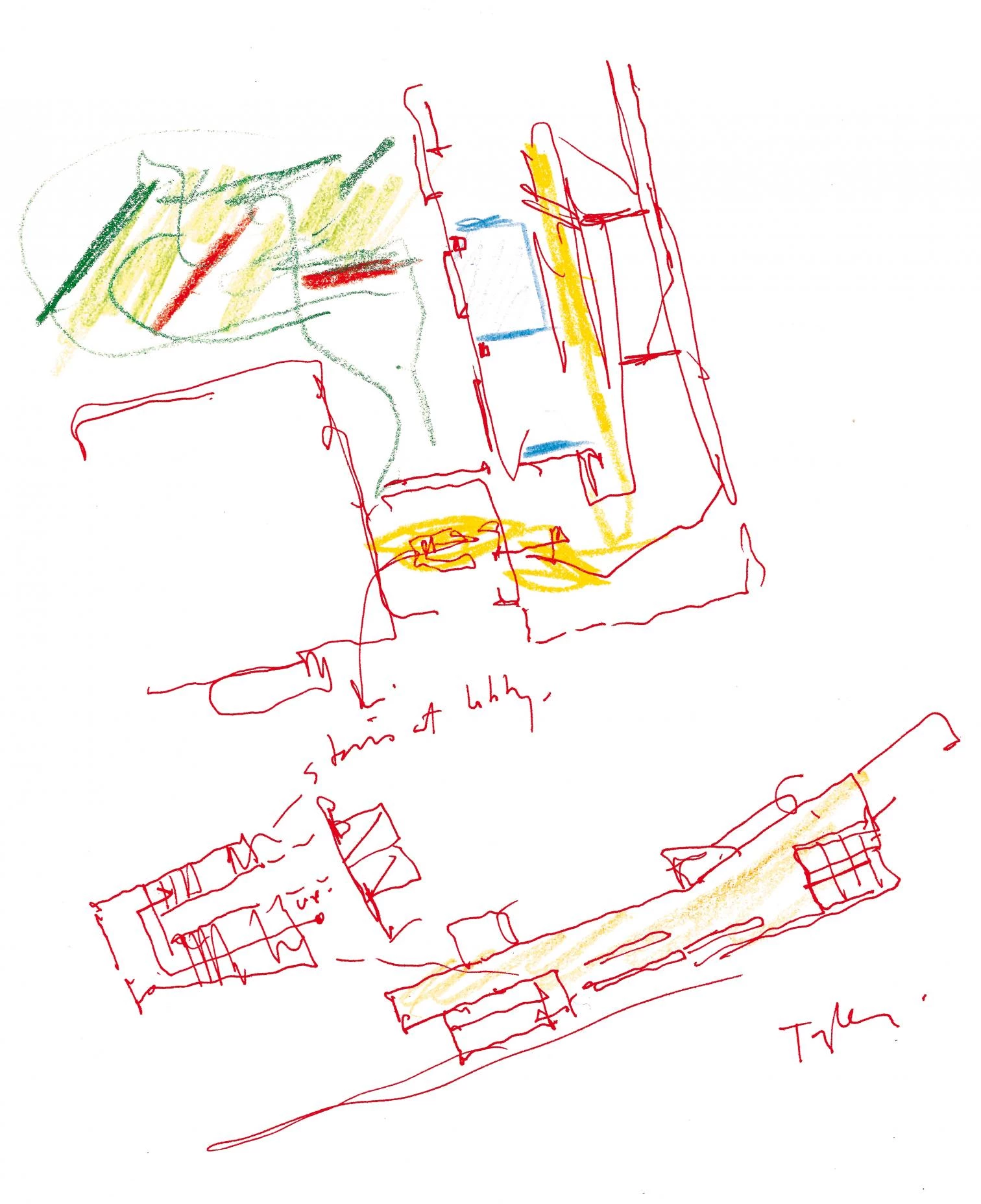

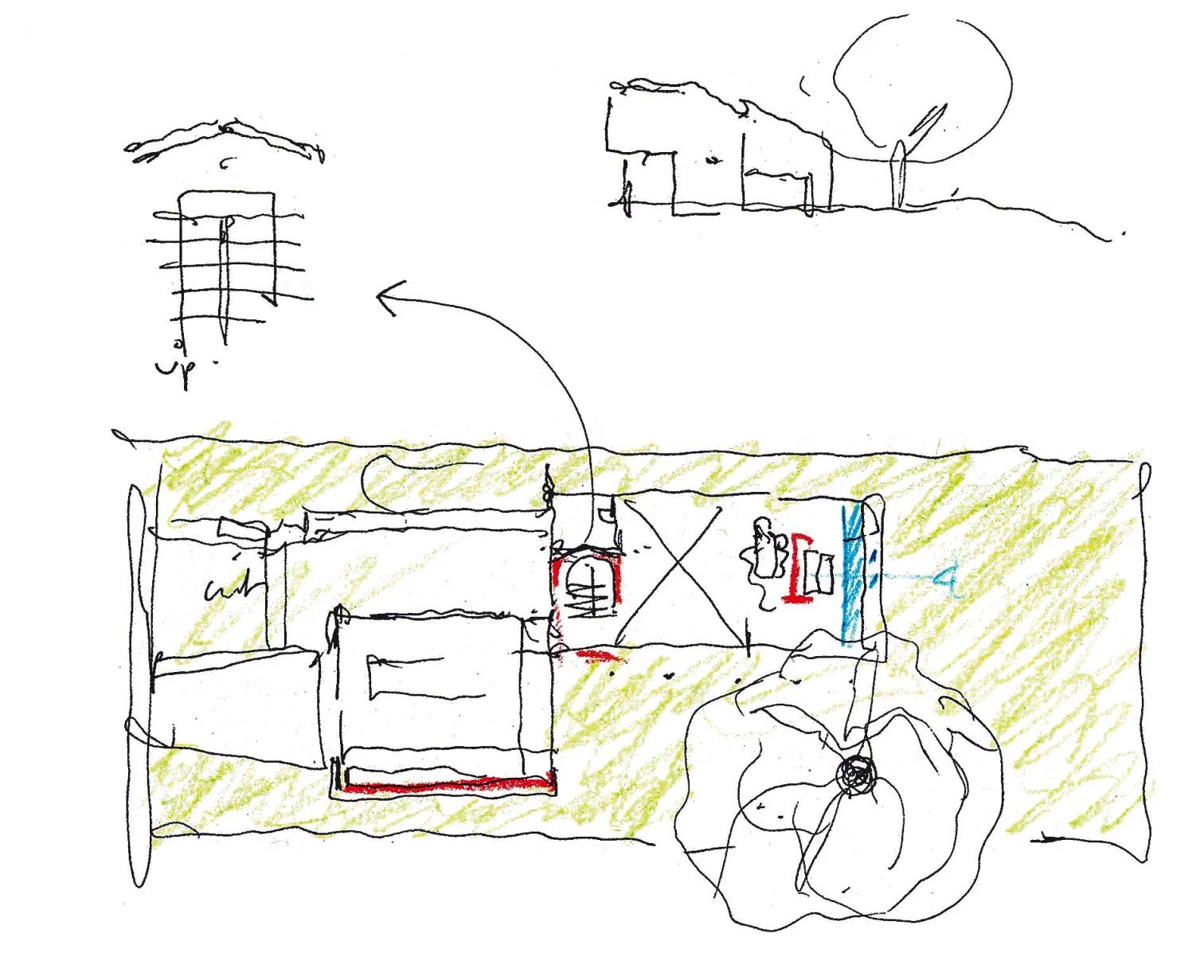

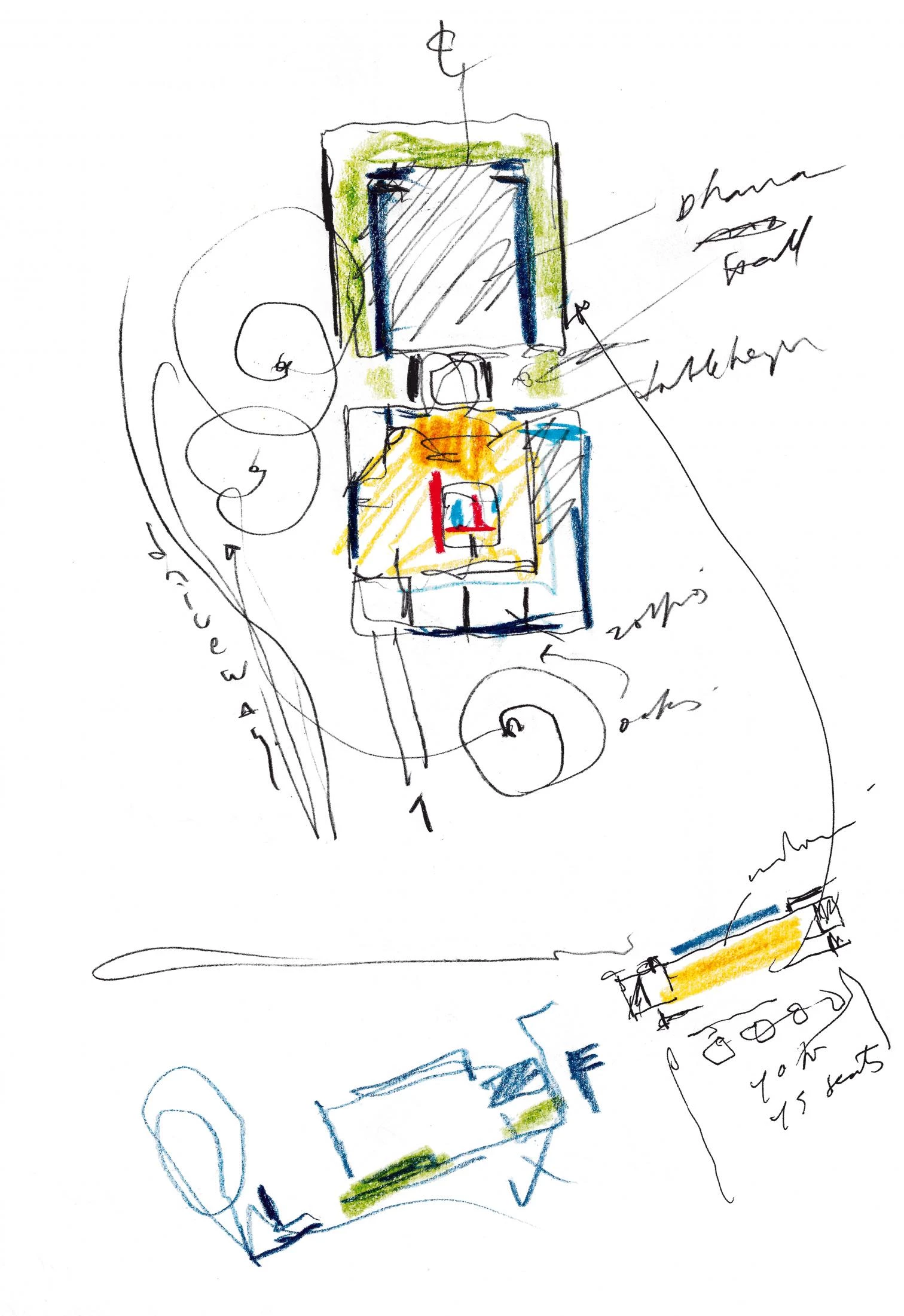

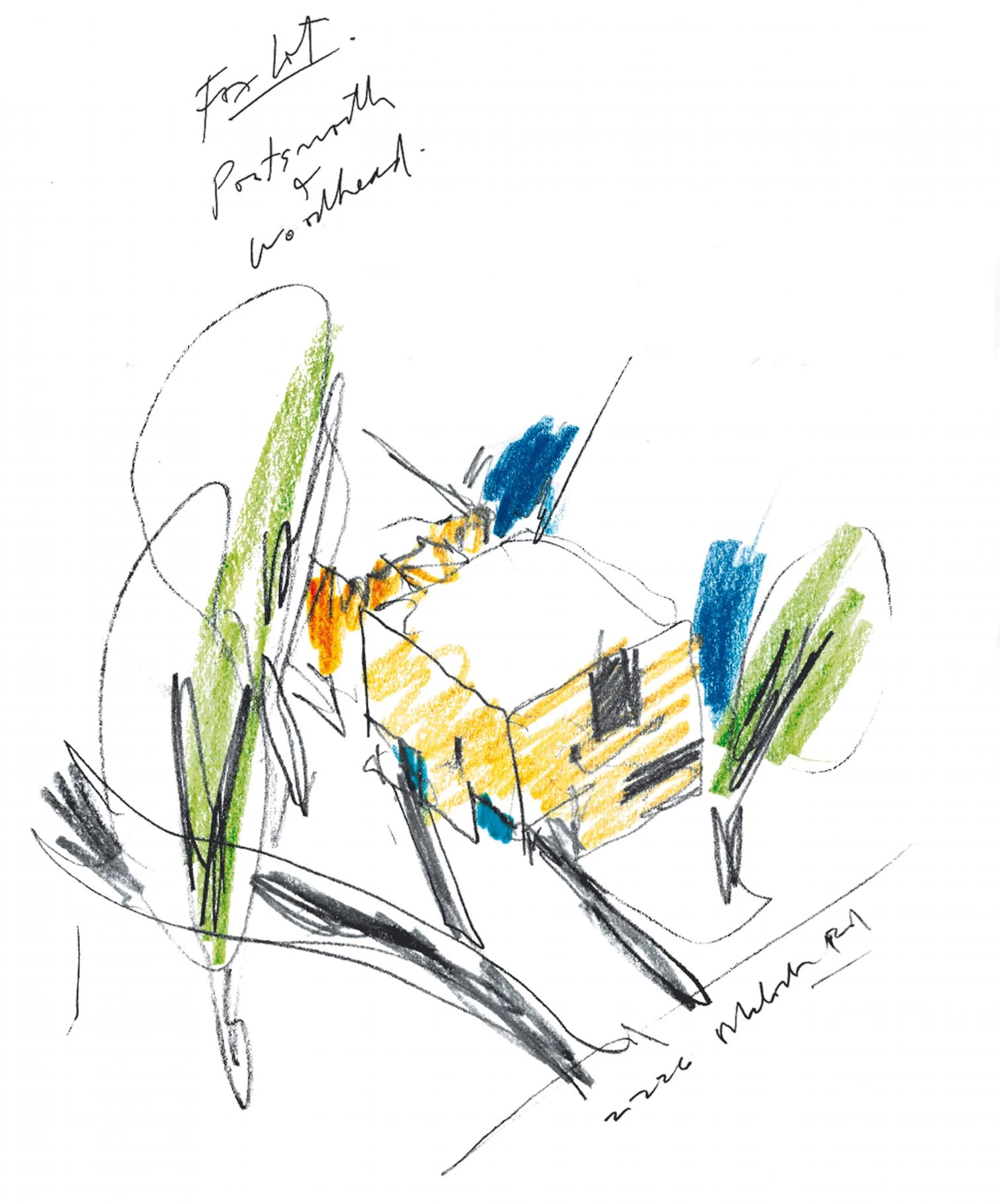

The economy with which Jiménez presents the buildings in this publication speaks to his search for order, clarity, and composure. Site plan, floor plan, an elevation, and, or, a section describe his methodical exploration of external surroundings, light and orientation, spatial program, and construction processes and materials. Colored sketches from his notebooks indicate how he uses drawing to focus his awareness on site relationships, spatial organization, and construction details. The chronological sequence in which the buildings are organized enables readers to see how he investigates architectural preoccupations across a series of designs. This linear manner of presentation also makes readers aware of how consistent Jiménez’s architecture has been over thirty years and how he has worked out his ideas without being distracted by cyclical shifts in the discourses of architecture since the 1980s.

Carlos Jiménez is not isolated from these discourses. As a member of the selection committee for the Pritzker Prize in Architecture between 2001 and 2011, he traveled the world to meet architects, visit their buildings, and engage with them in lively discussions about architecture. He is a professor of architecture at Rice University in Houston and he delivers lectures, speaks at symposiums, and participates in architecture school juries as well as architectural design competition juries globally. Yet while conversant with contending theories, practices, and personalities, Jiménez adheres to his personal architectural convictions with modesty and assurance. The confidence and radiance that his buildings emit contrast with the aggressive eccentricity associated with the buildings of so many global star architects of the early twenty-first century. Jiménez’s architecture is distinctive, as this compilation of works demonstrates. But it doesn’t seethe with unrestrained formal ambition. Jiménez does investigate the use of what might be described as “strange-making” devices in some of his buildings, perhaps to ward off a simplicity that might otherwise become too ingratiating. Austerity is an integral component in the economy of Jiménez’s architecture, but so are ingenuity, wit, and luminosity.

Over thirty years of work, Jiménez has stayed faithful to an efficient yet calm and poetic architecture, one that sets fashions and eccentricities aside.

Early Works

Like the interior of the Red Studio, Jiménez’s early buildings display affects he continues to explore. The Blue Studio (which began as an addition to the Red Studio) brings the color of the sky down to the neighborhood in uncelestial Houston where Jiménez has worked and lived during his whole career. At the Houston Fine Art Press, Jiménez devised an ingenious sectional organization that resolves everything that is problematic about the press’s site; the pink-painted stucco facing intimates the flush of enthusiasm that ensued from this discovery.

Jiménez used the L plan of an existing house to configure outdoor space when he remodeled the Beauchamp House; he then introduced contoured ceiling planes to shape interior volumes. He qualified the planar simplicity of the Chadwick House by incising the voids of the porch and windows into its wood clapboard wall; the cockeyed stacking of square windows cleverly mobilizes the static wall plane. At the Lynn Goode Gallery, he introduced shallow planar recession by differentiating the primary wall plane of orange stucco from the inset wall plane of ribbed and coated steel paneling. Within, square upper windows bring surrounding live oak trees into the gallery.

Jiménez shaped the Neuhaus House in an L plan to enclose its rear patio. He framed one end of the street front of the house with an asymmetrical flattened curve whose leading edge gives the house its dynamic profile. At the Central Administration and Glassell Junior School Building of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, he adapted the L plan to an institutional building in order to define a reciprocal rear patio. Additionally, Jiménez used curved and diagonally inclined roof profiles externally to differentiate the building’s internal uses, and he shaped an ethereal interior that makes working in this building a sublime experience.

At the Saito House, Jiménez preserved yet reinterpreted an existing house by juxtaposing window openings to articulate his reorganization of interior space. With the Lott House, he introduced the affect of ambivalent symmetry as a method of asserting, then qualifying, centrality as an ordering device.

Already in his early works like the Red Studio or the Neuhaus House, Carlos Jiménez resorted to abstract planes, squares, diagonals, and color fields that have become so characteristic of the architect’s work.

Jiménez produced an architecturally reserved building for the Spencer Studio Art Building at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts; he configured the building in a J plan to contain diverse program spaces. The sobriety of the exterior of the Spencer Building is matched by the ethereality of interior spaces, which engage the building’s surroundings with subtlety.

The Jiménez House, located across the street from Jimenez’s studio complex, grew into an L plan arrangement with his addition of a rear wing. The L plan is Jiménez’s preferred plan configuration for single-family houses. The introverted attitude of the Jiménez House, with big window openings on the upper floor (or looking only into the rear patio on the first floor), is characteristic of buildings Jiménez has designed for his own use.

In Praise of Modesty

At the Irwin Union Bank in Seymour, Indiana, Jiménez employed ambivalent symmetry to give presence to a building located amid the suburban sprawl typical of American towns and cities. The rising diagonal of the canopy shading the bank’s drive-in stations mobilizes spatial buoyancy to enhance the visibility of the little building.

The essential quietness of Jiménez’s architectural approach is evident in his entry to the invited competition for the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. Designed to be built adjacent to Louis I. Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum, Jiménez’s proposal attests to his determination to design buildings that respond to a client’s site and program rather than resorting to spectacular assertions of formal bravado. Jiménez’s sensitive interpretation of the museum’s rolling site, his use of gallery wings to enclose interior courtyards, and his provision for lighting the galleries with skylight demonstrate his attentiveness to the spatial condition in which works of art are exhibited.

In addition to the Irwin Union Bank in Seymour, Jiménez has designed a building in nearby Columbus, Indiana, a town made famous by the program begun in the 1950s by J. Irwin Miller and the Cummins Engine Foundation to commission the foremost architects in the United States to design buildings in Columbus and surrounding communities. The Cummins Engine Company was Jiménez’s client for the Cummins Child Development Center, a one-story pre-school and kindergarten located on the bank of Haw Creek near Cummins’s major plant and office operations. In this building Jiménez experimented with the juxtaposition of window openings and steel panels that contrast in texture and color with the gray brick walls to effect scale differentiation. He emphasizes the continuity of horizontally aligned windows that scale the center down to the size of its students.

Works like the Peeler Art Center, the Fort Worth and Nelson Atkins museums, and the Tyler and Spencer arts schools show how the architect manages to blend civic vocation with poetic sensibility.

A second commission from the Cummins Engine Company for a diesel engine sales and service building prototype was built in the corporation’s Southern Plains Division alongside a freeway in Houston. Jiménez applied the company’s colors to concrete tilt-wall panels, which incorporate the rising diagonal of a leading edge, in a plan based on programmatic differentiation. The difference in expectations and resources between a commercial building and a purpose-built institutional building is evident in contrasting the Cummins Engine building with the Peeler Art Center on the campus of DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana. The space-shaping floor plan, contoured profiles and inflected wall planes, and a contrast between the normative and the iconic (the windows illuminating the painting studios) subtly emphasize the Peeler’s programmatic complexity and Jiménez’s effort to reinforce community and campus space in Greencastle with its design.

Ethical Minimalism

Jiménez’s ability to put meager budgets to work was tested with The Peavy, his design for an affordable house prototype devised for an exhibition organized by Michael Bell in 1998. Here Jiménez treats minimalism not as a decorative style but as an ethical imperative in order to craft a spatially ingenious, environmentally sustainable single-family house.

Jiménez’s competition entries for expanding the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City and transforming Booker T. Washington High School in downtown Dallas into a high school for the performing and visual arts display his penchant for responding to complicated programs on constrained sites with self-effacing straightforwardness and clarity. As his drawings and studies demonstrate, Jiménez’s competition entry for One Museum Place in Atlanta was designed to absorb the pressures exerted by surrounding buildings and landscapes.

In Houston, Jiménez made the two-story Girouard House both spatially simple and perceptually complex by the way he pivoted its offset wings. It is the first building to which he applied saturated shades of green to evoke the intense verdure of Houston. The L plans and green walls of the Marvil-Smyth House, the Hanneman House, and the Photography Studio in Houston expand on this investigation. The Whatley Library, in the suburbs of Austin, contains a personal library, serenely unified beneath a contoured ceiling. The little building is marked by ambivalent symmetry: it is centered on a ground-floor void, a “dogtrot,” through which cars can drive, Jiménez’s concession to the preoccupations of Austin’s architectural community with Texan regional vernacular traditions.

Built within low budgets and completed with simple and rigorous details, Jiménez’s houses alter the traditional isolated type around a courtyard to establish an open relationship with the outdoors.

Jiménez based the Crowley House in Presidio County, Texas, near Marfa, on a Z plan configuration in order to frame multiple patios and to make the big house seem compact inside. He treated interior spaces as observatories for surveying the stunning atmospheric effects and long-distance vistas of the Texas Trans-Pecos region.

In the Indianapolis suburb of Fishers, Indiana, Jiménez designed his first, freeway-side speculative office building, constructed and occupied initially by the Irwin Mortgage Company. The bluntness of this four-story, slab-shaped structure and the dissonant syncopation of its curtain walls are strange-making affects that identify the building with infrastructure as much as with architecture, Jiménez’s newly formulated strategy for building amid the landscape of American suburban sprawl. Jiménez pursued this infrastructure proposition in his design of two buildings for Rice University, both essentially warehouses: the Library Service Center and the adjacent Primary Data Center. Both are constructed of concrete tilt wall panels painted deep green. Jiménez had their tilt walls cast with diagonally flared profiles to enhance the effect of sun and shadow on what would, otherwise, be flat wall planes.

Jiménez’s third art school building is the Tyler School of Art at Temple University in Philadelphia. Built on half a city block in North Philadelphia that it shares with other buildings, the Tyler School of Art is configured in a J plan to frame an interior courtyard. Austere externally, it is enlivened by brick walls scored into big scaled panels, glass curtain walls threaded with horizontal bands of blue glass, diagonally inclined leading edges that rise to contain tall, north-facing, upper-level studio windows, and public interior spaces suffused with color.

Color also figures in Jiménez’s first high-rise building and first European building: the seventeen-story, eighty-three-unit Résidence Ambre, constructed as social housing in the center of the French new town of Évry, Essone, a suburb of Paris. Jiménez faced the vertical voids in which he stacked balconies with amber colored precast concrete panels, playing off the sobriety of the gray terra cotta panels that clad the exterior faces of the tower. What was to have been Jiménez’s second European project, a commemorative space, community center and social housing complex, represented an intricate intervention in the Beniopa neighborhood of Gandía, Valencia, Spain.

Spaces for Life

Jiménez’s most recent work stems from a single client, the Houston lawyer Tim Crowley, who divides his time between Houston and Marfa. Crowley is the client for Jiménez’s addition to the Crowley Theater (formerly Bewley’s Big Bend Feeds store) in Marfa, radical alterations and additions to the one-story Childers Building that have transformed it into the four-story Hotel Saint George, the design of the adjoining Saint George Hall and of a one-story office building on E. El Paso Street in Marfa. The Hotel Saint George, raised atop the Childers Building, is a thick, block-like presence, a departure from the thin sections characteristic of Jiménez’s buildings. The hotel’s new upper floors, constructed of light steel framing faced with stucco panels painted two shades of radiant white, are articulated with horizontal and vertical joints, mitigating the building’s bulk and enabling it to reflect the brilliant daylight of the Trans-Pecos region.

The adjoining Saint George Hall, a freestanding, steel-framed shed building containing the hotel’s event spaces and a walled and planted patio, is aligned with the railroad tracks that slice through the center of downtown Marfa. The hall is faced with ruddy blocks of clay tile, a material commonly associated with industrial construction. Jiménez incorporates a split section into its roofline to bring skylight down into the interior of the hall. Jiménez also leaned on this sectional strategy when he added a sidebar of service and support space to the Crowley Theater. The office building, which stretches out along the railroad track behind Saint George Hall, is an exercise in precisely proportioned horizontal alignment, shallow planar recession, and ruddy coloration (it too is faced with clay tile block). In Tim Crowley, Jiménez has found a client who values simplicity and understands that architecture is not about adding “style” but shaping generous spaces to contain life.

Jiménez concludes this survey with the temple complex for Won Buddhism of Houston, located in the Spring Branch section of Houston. Wedged between the truck yard of a steel erection company, an auto-parts store, a mini-warehouse, and remnant single-family houses from the 1950s shaded by immense live oak trees, the temple sits in the midst of a landscape that summarizes the contradictions of Houston the rustic metropolis. Jiménez layers space on the flat site, where, to comply with municipal parking requirements, he had to surrender substantial open space to on-site parking. Preserving existing live oak trees, Jiménez positions the dharma hall behind the community building and minister’s residence, wrapping the hall with an external wall to enclose a shallow garden, visible from inside through low-set windows rising from the floor. The dharma hall is a unified volume. Daylight is filtered through upper-level window slots. A suspended ceiling plane, contoured with a crease, will distribute skylight within the hall. Jiménez’s ability to communicate spiritual calm and ethereal luminescence through simple diagrams derives from the ways one experiences his existing spaces, making it possible to predict the sensations embedded in these line drawings.

Architecture of Emotion

Carlos Jiménez has based his approach to architecture on the square, the rising diagonal, planar recession, and the infusion of color. Atop this foundation he has erected structures in which opportune sections, reciprocity between indoor and outdoor spaces, contoured ceiling planes that shape volume and distribute daylight, leading edges that become defining profiles, ambivalent axes that stabilize without centering, wall planes and voids layered to construct scale differentiation, juxtaposition of the iconic and the ordinary, extracting spatial cleverness from spatial discipline, subverting complacency with strange-making, and suffusing space with luminescence, ethereality, and silence are affects that compose an architecture of calmness, modesty, purposefulness, and serenity. If these virtues seem not so relevant in a world in search of the unprecedented and spectacular, they do lead to works of architecture that are consistently gratifying to inhabit.

While the Crowley House and Theater open up to the desert landscape of Marfa, other works like the Won Buddhist Temple in Houston are designed as compact volumes to generate more controlled and hermetic spaces.

Time and change have affected Jiménez’s buildings and practice. Transfers in ownership, demolition, bankruptcy, divorce, death, floods, competitions won by other architects, bland repainting: all serve to demonstrate that even an architecture of delicacy and refinement must be tough and resilient if it is to endure, especially in Houston where there is no consensus affirming the cultural value of architecture. As Jiménez’s teaching colleague Lars Lerup observes, Jiménez is optimistic, cheerful, and willing to solve problems. He works hard to construct simple spaces that are emotionally compelling.

The buildings and projects in this monograph reflect Jiménez’s constancy and dedication to architecture. They forcibly remind those who experience his buildings, whether in life or in print, that even in the everyday world architecture possesses the capacity to be an instrument of spiritual exhilaration.

Stephen Fox is a Fellow of the Anchorage Foundation of Texas

[+]