On sunday 12 March, a young president and an ancient pope lived the most beautiful day of their lives. From the balcony of his party’s headquarters on Génova street, José María Aznar celebrated an electoral victory that wraps up the historical cycle of 20th century ideological politics, once and for all banishing the shadow of the Spanish Civil War from national life. And in St. Peter’s Basilica, John Paul II officiated a solemn penitential rite that ushered the Catholic Church into the third millennium, culminating his pontificate with a public confession of the sins committed by Christians in 2000 years of troubled history.

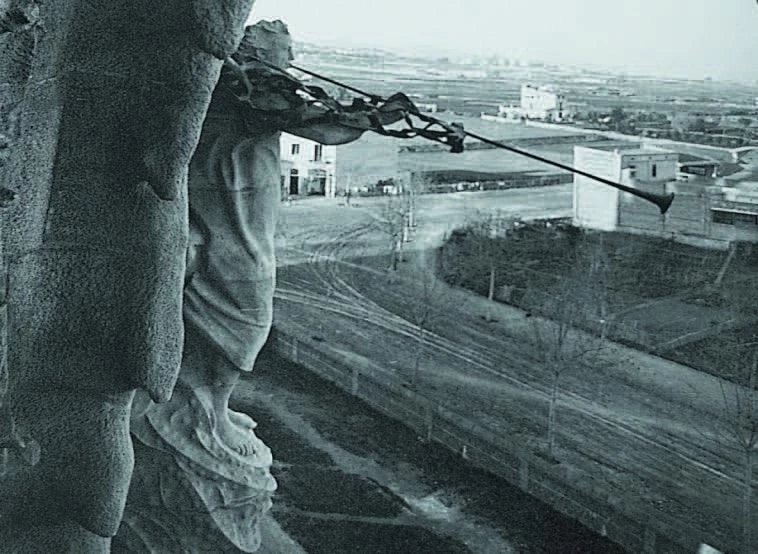

The Vatican has initiated the beatification process of Antoni Gaudí, the construction of whose Sagrada Familia church is illustrated by images such as the one below, showing the facade of the Nacimiento around 1908.

Embracing a wooden Christ, the fragile Wojtyla begged forgiveness and gave it in return, shaking the memory of a century that has seen religious persecutions, but also the Church’s complicity with ominous regimes and its ambiguous prudence in the face of the Holocaust. It was the hour, so to speak, for the millenary repentance of a Church triumphant. How ironic, then, that it should have coincided with a generous chain of canonizations of religious victims of the Spanish Civil War, precisely at a time when politics in our country is moving away from the ideological and confessional polar-ization that has made the century an open wound. New on this impressive roster of sanctity is the architect Antoni Gaudí, whose beatification process was authorized by theVatican on the eve of the great liturgical ceremony that congregated the Curia in a self-inculpating ritual circle under Michelangelo’s dome, around Bernini’s baldachin, invoking the “purification of memory” through the dolorous declaration of the seven deadly errors of the Church. All this while polls in Spain clamorously absolved the Right of its historical sins, the same merciful polls and the same ten million ballots that in 1982 had settled the Left’s debt to the past.

Free of the burden of memory and ideas, architecture can finally attain the fullness of its amnesiac hollowness. Reduced to a self-referring sign, it becomes a symbolic currency which, like Vaspasian’s taxes on latrines, non olet, reflecting in its odorless innocence the accidental condition of its origins. Arzalluz may go farther than Haider in his defense of ethnic identity, but this does not prevent him from adorning himself with the Guggenheim’s explosion of titanium; Fraga will never shed the stigma of having been a minister under Franco, but his intellectual sensibility allows him to welcome, for Santiago’s emblematic works, the Siza of the Revolution of the Carnations and the Eisenman who has gone through Bataille and Derrida; and Aznar will remain a routinary tax inspector, yet under him the Prado Museum and the Reina Sofía will be enlarged by figures like Moneo and Nouvel. The mythical genealogy of leftist modernity, sufficiently mutilated by Terragni’s fascism, Le Corbusier’s wooing of the Vichy regime or Mies’s flirtation with the Nazis, collapses altogether in the amiable and trivial society of spectacle.

Gaudí’s biography and the vicissitudes of the project and construction of the Sagrada Familia provide a revealing portrait of Catalonia in the turn-of-the-century. To the first years of the 20th belong the three photographs of the Nacimiento facade and the belfries, with Barcelona’s half-developed Ensanche in the background, as well as one of the best known drawings of the temple by Joan Rubió i Bellver.

Undoubtedly aware that architecture is the only survivor of the contemporary shipwreck of ‘sacred art’, as a run-through of the latest works in the recently renovated Vatican Museums inevitably confirms, the Holy See has chosen Jewish authors for its Jubilee churches, in a rare subordination of doctrine to language that suggests a growing liturgical eclecticism and whose superficial theological base is surely preferable to the solid foundations of an esthetic mediocrity like Madrid’s Almudena cathedral, a model we can only hope our cardinal Rouco Varela (one of the candidates to succeed the present Pope) has not incorporated into the mental instruments of his approach to Rome. But this light architecture of the diminishing piety that accompanies smug prosperity contrasts with the lethal or redemptive violence of illumined sects or religions in conflict, as the Pope knows only too well and may have had yet another chance to verify during his trip to the Holy Land, perhaps the last of many undertaken by this wanderlustful pontiff and surely the most touching given its nature as a return to origins. And it is in such archaic redoubt of hardened faith and the categorical dogma of century ends and beginnings that the most genuine and therefore least digestible architectures can be found.

This is the rare and terrible substance that makes the work of Gaudí, a brilliant architect possessed by the vertigo of building an expiatory temple, a believer and ascetic who was first portrayed in the press kissing the ring of a bishop, and an obsessive liturgist who erected the Sagrada Familia in the shape of the magic mountain dreamt of by Catholic Catalanism; a “Montserrat of the spirit” who would find his poet in Maragall, and lead the caustic Xénius to write: “...I am terrified at the thought of the fate of our people, forced as it is to bear upon its poor and precarious normality the weight, grandeur and glory of these sublime abnormalities: the Sagrada Familia, Maragall’s poetry...” Eugeni D’Ors would have nothing to complain about today. Packaged in a 13-episode TV series to be presented in the Cannes Film Festival starting April 4, and with a good chance of being beatified in time for the 150th anniversary of his birth in 2002, the pasteurized Gaudí of his memorial year will no longer be a sublime abnormality, but a spectacle of placid convention which these Lenten musings resignedly situate in the kingdom of this world.

A prolific bibliographical industry surrounds in any case God’s servant Antoni Gaudí i Cornet, whose already mentioned diocesan process of beatification has received the green light from the Vatican congregation for the Causes of Saints, but two recent reeditions in large format are worth mentioning as complementary works. Gaudí, el hombre y la obra (Gaudí, The Man and the Work) is a colossal volume of Lunwerg that reproduces the pious biography that his friend and confidant Joan Bergós, a fellow-architect, dedicated to him. First published in Catalan in 1954 and in Spanish in 1974, the work of this reverent disciple of Gaudí is an affectionate and colorful testimony of a life and oeuvre, succulently accompanied on this occasion by current photographs taken by Marc Llimargas, also an architect. Antoni Gaudí is a formidable study by the Barcelona architect and professor Juan José Lahuerta, originally published in Italian in 1992 by Electa, and now reprinted by the Spanish branch of the company with its usual quality. Lahuerta explores the “horrific and edible” architecture of Gaudí through seven interlocking episodes, offering a detailed and enthralling fresco of social, intellectual and religious life in the bourgeois Catalonia of the late 19th century, all narrated with rigor and illustrated with intelligence. Blessed Gaudí will never lack the devotion of architects.