I have always been intrigued by the Calatrava case. The work of the Valencian architect, engineer and sculptor enjoys a public acclaim that most of his colleagues do not deem him worthy of. From the very beginning, the extraordinary popularity of Calatrava’s constructions has been accompanied by reticence on the part of critics. Perhaps because he straddles disciplines, neither architects nor engineers nor sculptors consider him one of their own. Then, settling in Zürich makes him as foreign among Swiss as it renders him remote to Spaniards. Still, neither his interdisciplinary vocation nor his extraterritorial situation fully explains the extreme hostility he frequently arouses. I myself have been on many competition, biennial and award juries, and never have I noted as much animosity as that provoked by the projects and works of the Valencian from Benimamet. It is true that early success elicits distrust if not envy; true that most of his hagiographers, by insisting on likening him to Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, invite only derision; and true that the abrasive character of some of his controversies with clients, colleagues and disciples hardly helps to increase the number of his admirers. Nevertheless, at least where architecture is concerned, the reasons for the coolness toward his persona must undoubtedly be found elsewhere.

The vast Gothic structure of Valencia’s Museum of Science raises Calatrava’s stature among the general public, but does not dispel his colleagues’ mistrust, who tag him as a ‘genre architect’ and find his work too engineering-oriented.

In my opinion, the work of Calatrava is among the most important and representative of our times. To be sure, this judgment is not shared by the majority of my architect friends and colleagues in the university and publishing world. But when they censure the rhetorical colossus of Seville’s Alamillo Bridge, with its vain harp monumentalizing nothingness, I think of the weightless elegance of the Kuwait Pavilion at the Expo, its animated forest of palms and fangs culminating a decade of experiments with mobile and folding structures. When they ridicule the futuristic and naïf exhibitionism of the telecommunications tower of Montjuic, a design that hybridizes science fiction cartoons and gnomic treaties, I think of the formal intelligence of the Bach de Roda Bridge, a dazzling gesture that created an urban landmark in a dilapidated Barcelona zone while fabricating an emblematic image for Spanish modernity. And when they denigrate the unprecedented arch of the Mérida bridge by comparing it to the efficient severity of the Roman bridge crossing the Guadiana a few hundred meters upriver, I think of the parabolical slenderness of Bilbao’s Campo del Volantín footbridge, a harmonious feat of concrete, steel and glass that redeems a rough and anonymous estuary.

Surely it is not necessary to like the schematic and vulgar chromaticism of his watercolors to appreciate the firm line and trained hand of his sketches. One need not esteem the trivial constructivism of his sculptural pieces to admire the formal and rhythmical perfection of his immaculate models. And sharing his capricious disdain for structural optimization is not a prerequisite to lauding the technical meticulousness and professional exactitude of his detail drawings. When his work is discussed, the most immediate tendency is to dismiss him as a ‘genre’ architect: in the same way that filmmakers specialize in westerns or comedies, Calatrava is a specialist of engineering works, from bridges to transport buildings, where both the importance of structural spans and the protagonism of movement make his double training singularly appropriate. This would explain, for example, the success of his railway stations, from the topographic, landscapist rigor of the Stadelhofen in Zürich to the vitreous, Gothic luxuriance of the Oriente in Lisbon, passing through the symmetrical and winged eloquence of the station of Lyon’s Satolas Airport. It would also explain the architect’s scant fortune on the opposite end of the project range, residential works, where the cellular fragmentation of the brief allows few structural feats and the orchestration of uses calls for sociological sensibilities probably removed from Calatrava’s sculptural and symbolic ambitions.

His case in many ways resembles that of Bofill. The Catalan practiced architecture to enormous success and international recognition, closely attentive as he was to the mutations of taste, besides well seated in the theater of political and economic power. Nevertheless it did not help to surround himself, in his workshop, with a court of poets and philosophers. His colleagues immediately discounted him as “the Julio Iglesias of architecture” – an offhand denomination no one then suspected would be ironically endorsed by an ephemeral marriage of Ricardo Jr. to the singer’s daughter – and denied him all cultural legitimacy, expelling him to the outer confines of academic criticism. Still, very few today will deny that Bofill’s French urban designs and housing schemes of the seventies count among the most pedagogical and explicit manifestations of the postmodern esthetic, and this gives him a place, whether we like it or not, in the history of the architecture of our century.

The epithet most profusely assigned to Calatrava, in turn, is fallero, in double allusion to the Fal-las festival of his native Valencia and the figurative populism of his architecture, where anyone will easily recognize archaic forests and prehistoric skeletons, cetaceous bellies and Cyclopean eyes, spread wings, claws, beaks, feathers or ribs. Not even an excellent artistic and academic background salvages this Levantine descendant of Christian Jews, culminated by a doctorate at the ETH of Zürich; nine honoris causa doctorates from European and American universities; numerous solo exhibits of his work all over the world; and the host of recognitions he has received which hit a milestone last year with the Prince of Asturias Prize, a distinction heretofore granted to only two architects, the Brazilian Oscar Niemeyer and the recently deceased Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza.

On November 4, while his oeuvre is on display in the Palazzo Strozzi of Florence, Calatrava will be in Dallas receiving the Meadows Prize for the Arts, an award that includes $50,000 and which has in the past gone to figures like Ingmar Bergman, Arthur Miller and Robert Rauschenberg. This is another case where unanimous approval from the architectural profession is unlikely. But Architectural Record, the veteran magazine now linked to the American Institute of Architects, dedicates its July issue to the recent European burst of creativity that centers in two countries, the Netherlands and Spain, and two architects, Rem Koolhaas and Santiago Calatrava, testifying to the Valencian’s popularity in the United States, where he recently won the competition for the ‘time capsule’ of New York’s Museum of Natural Sciences, and where next year he is due to open a first building, an ambitious enlargement of the Museum of Art of Milwaukee, which shall spread the mobile steel wings of its gigantic brise-soleils on the banks of Lake Michigan.

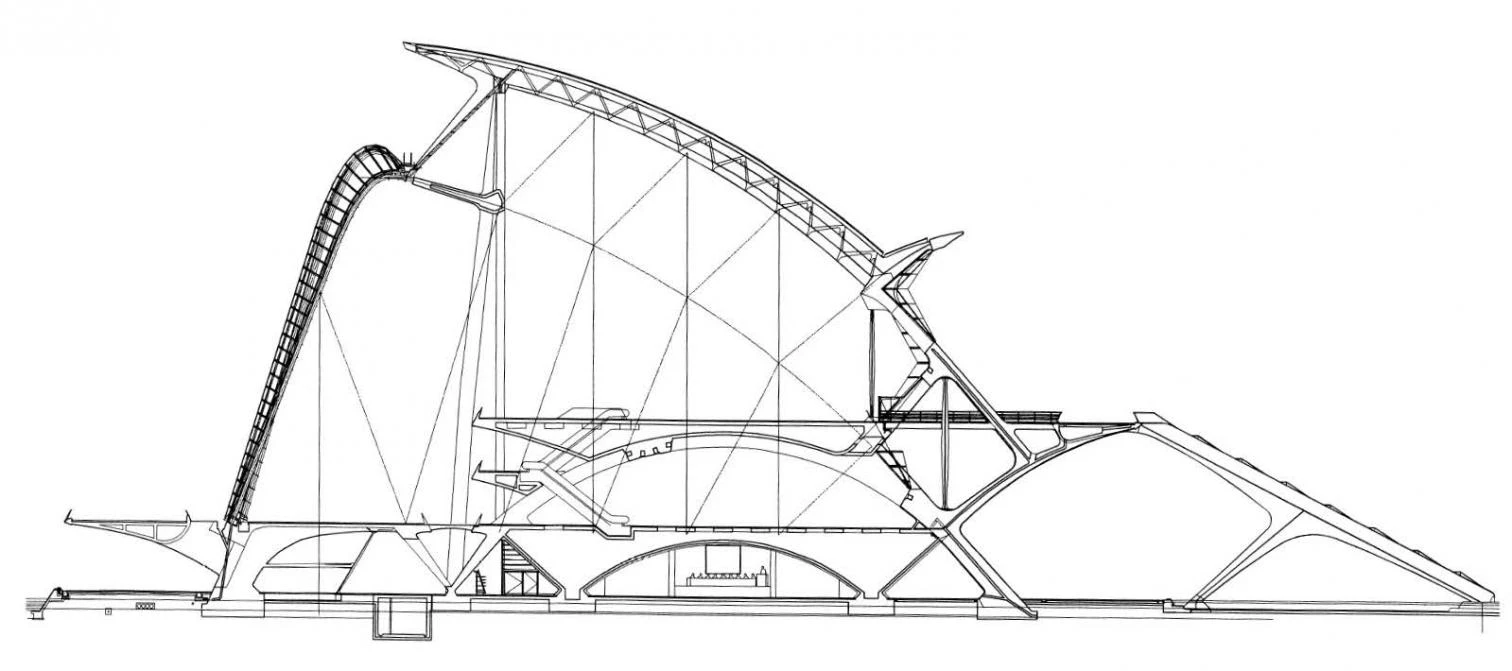

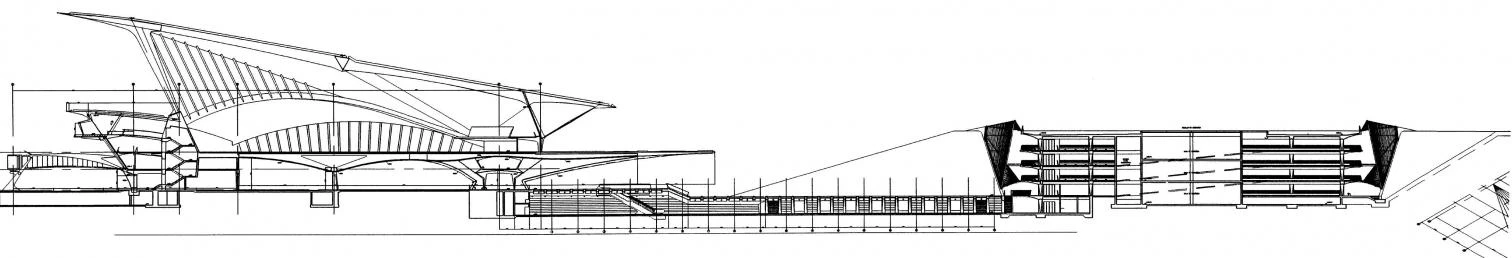

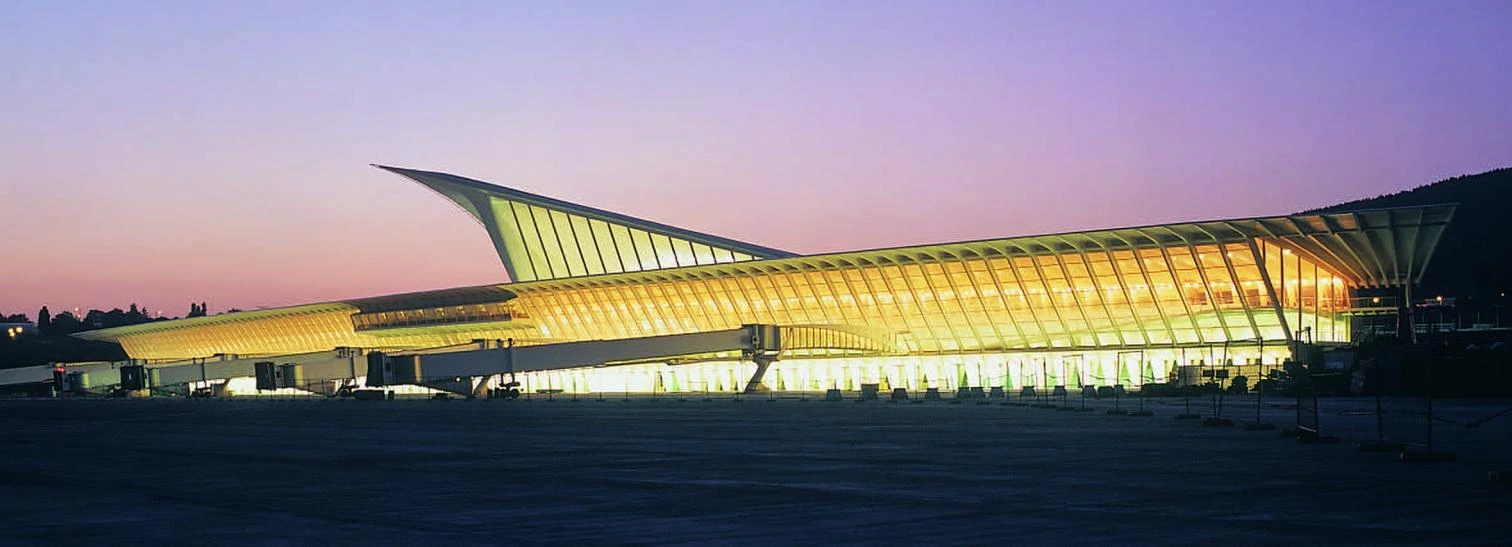

Bilbao’s Sondica terminal welcomes departing passengers in a luminous hall that extends a bird’s beak towards the runways, and houses the arrivals under rhythmic ribs, linked underground with the buried parking area.

Meanwhile, home in Spain, Calatrava wraps up two major works which will lift his stature in the eyes of the general public without dissipating the wariness of his critics. The terminal of Bilbao’s Sondica Airport – where he completed a sculptural control tower three years ago – is a large luminous hall of steel and aluminum that points, in the direction of the runways, a bird’s beak whose rising profile evokes those of surrounding mountains. The triangularly planned departures concourse, which welcomes travelers under the tensed curve of a glazed visor to then lead them to the projecting galleries of the boarding area, rises on a concrete plinth that accommodates arrivals under a rhythmical ribcage, connected by an underground pas-sage to an elegant parking lot dug into the land-scape. Here, the expected reference to Eero Saarinen’s TWA terminal in New York dilutes into a light and transparent construction, one recalling the optimism of fifties American architecture through slanted windows and the friendly edges of a slender and delicate frame.

And in Valencia, the colossal City of Arts and Sciences comes to an anticipated climax with the completion of the second of its three buildings, the formidable Museum of Science, which raises its mass of concrete ribs and glass spikes beside the magical eye of the planetarium, opened last year. Now begins the wait for the complex’s third element, the Palace of the Arts which in the final project replaced the initially contemplated communication tower. The museum – based on the multiplication of a structural module, following a logic of extruded sections that is very frequent in Calatrava’s architecture – presents to the north an accordion of glass that drops like an ice cascade from a vertiginous corbel sustained by five huge concrete trees, and lowers to the south like a spine bristling with pinnacles, needles and buttresses, forming a Gothic interior that evokes both a petrified forest and the secret worlds found behind water curtains in children tales. Valencia’s crystalline Niagara Falls embraces an oneiric and titanic universe that belongs more to the age of gods or heroes than to the age of men, and an infinite space that is more conducive to shock than to reflection; a place that seemingly will admit only an epic conception of science. No different, in the final analysis, from Calatrava’s vision of architecture; a heroic and sacred task which his admirers will find Homeric and his detractors chimeric, when in reality it may be no more – and no less – than the structural and sculptural crystallization of the contemporary urban spectacle.