Double Theater of the World

The new residence for Prince Felipe and the last installation by Juan Muñoz at the Tate represent the scenographic extremes of a diverse and divided Spain.

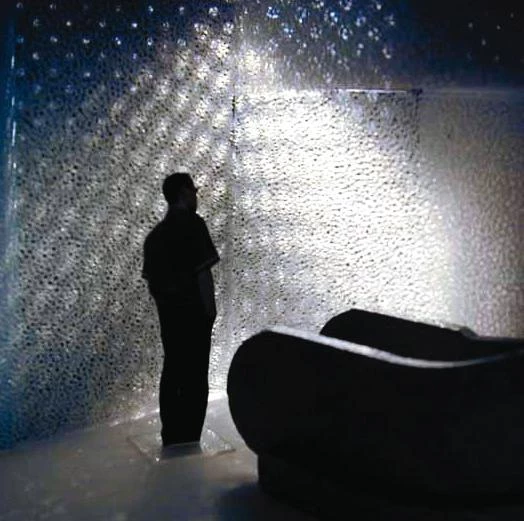

In Spain, the fall term began with Eva Sannum and without Juan Muñoz. The appearance of the Norwegian fashion model in Oslo’s royal wedding and the sudden demise of the Madrid artist in Ibiza wrapped up an August clouded by the tragic tides of African emigration and the grotesque revelations of Celtiberian corruption, combined with the usual savagery of terrorism and the Goyaesque death in Bordeaux of veteran actor Francisco Rabal. In May the model had accompanied Prince Felipe on a visit to the Madrid site where his new home is going up, and the constitutional debate sparked by the possibility of a marriage brought to the fore the first im-ages of what in future will be the residence of our head of state, instead of the modest palace currently occupied by the king and queen. And in June the sculptor had unveiled in the turbine hall of London’s Tate Modern a monumental installation with figures and architectural spaces – his most ambitious project and, after his premature disappearance, also the intellectual will of the most important Spanish artist of his generation. The house of the prince, scheduled for completion in the early months of 2002, and the installation of Muñoz, due for dismantling around the same time, provide two opposed icons of contemporary Spain: the stub-bornly symmetrical and traditional representation of power in its domestic version, and the ambigu-ous scenography of solitude, withdrawal and dis-tancing in a fragmented society.

The premature death of the Spanish artist turned the Double bind set-up into his intellectual and artistic testament, which serves to link the Baroque tradition of illusionist scenographies with the uncertainties of today.

The crown prince and his sisters have a relaxed attitude toward marriage that seems to suggest a modernization of the Spanish monarchy, but the new building in the grounds of the existing Zarzuela palace reflects the most rancid and formal traditionalism. It conceals the hygienic and athletic sensuality of the gymnasium or the Jacuzzi behind a stiff dressing more in tune with the prince’s uniform as captain of a corvette than with the gown worn by Eva Sannum in the Norwegian nuptials.With its volumes arranged in an innocuous symmetry – more eighteenth-century than beaux arts – to which the ceramic slope of the roofs, the palatial stone-framed openings, the vernacular windows and a battery of small chimneys are all subordinated, the mansion tries to reconcile its residential and representational functions through a hackneyed classicism that inevitably recalls the historicist tastes of his distant cousin, Prince Charles: another heir to the throne who has decided to indulge in the small pleasures of the manie de bâtir during the interminable wait for his turn on the throne.

Unlike the Prince of Wales, however, the Prince of Asturias is building his house out of state funds and on land belonging to the National Heritage. This makes the absence of public debate on the project censurable. Recently an object of controversy for having accepted the Spanish firm Porcelanosa’s gift of a fountain for the ‘Islamic’ garden of his country house of Highgrove, the Windsor heir hasfrequently been criticized for his attempts to impose his conservative aesthetic preferences on British society. In the Spanish case, the construction of what will be the head of state’s residence has proven a forfeited opportunity to collectively decide what architectural language must be presented to the world by a young democracy and an old monarchy in the process of aggiornamento. A building of this nature is the inevitable stage and backdrop of political pro-tocol and state visits, and we can only lament that such representation of Spain has not first been properly discussed by Spaniards.

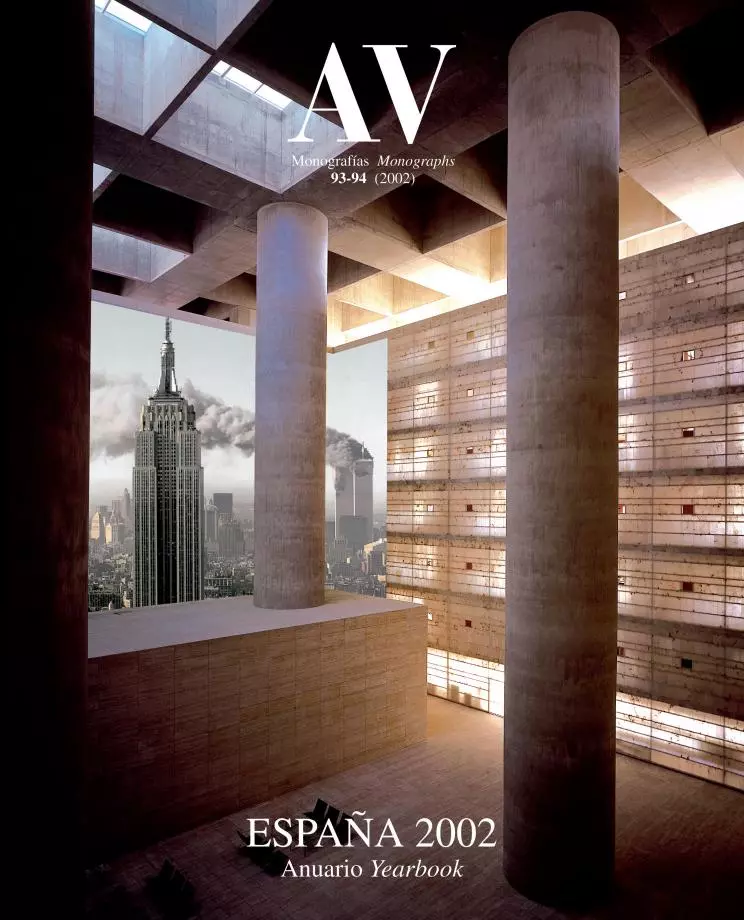

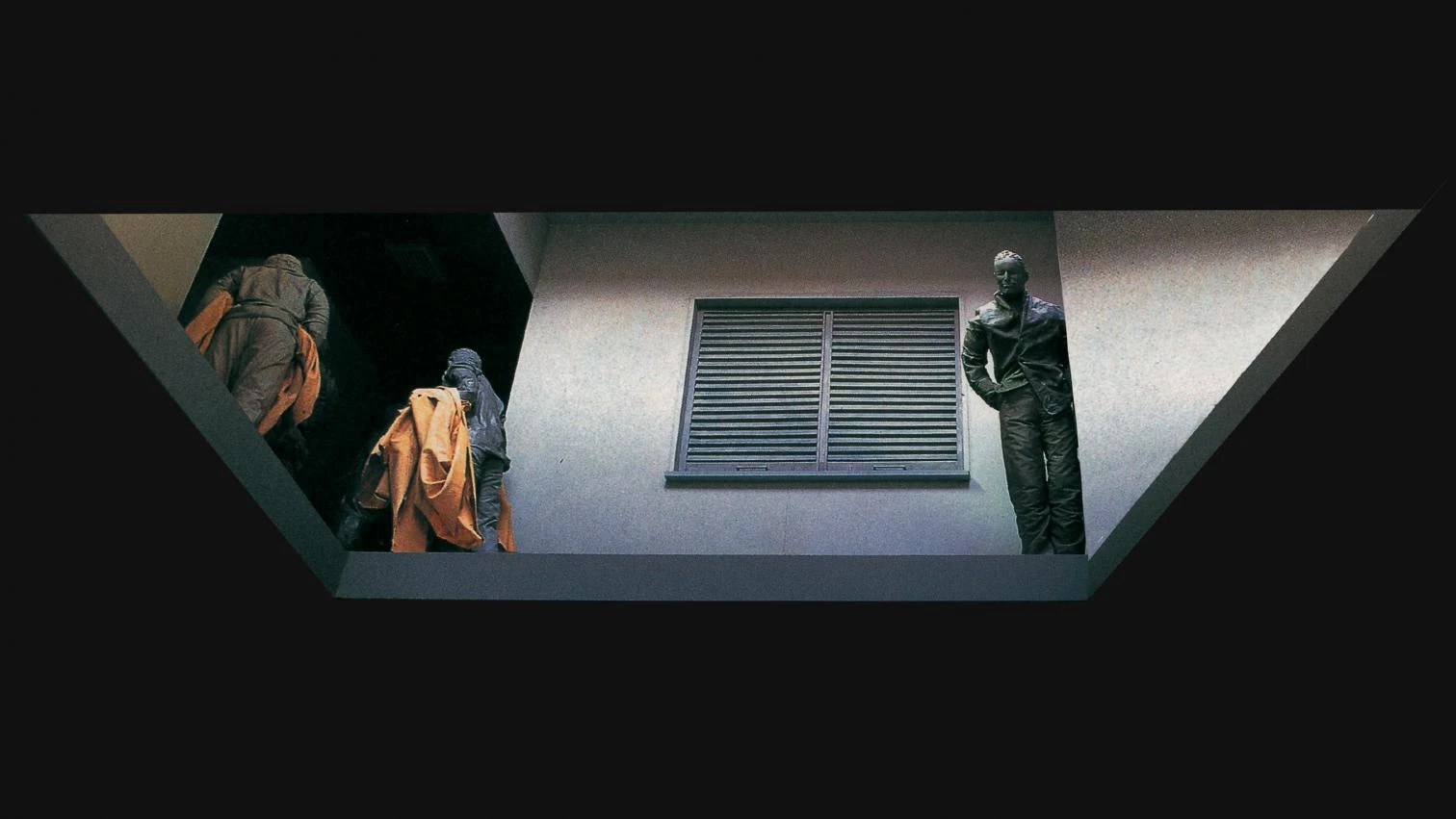

Installed in the building remodelled for the Tate by Herzog & de Meuron, the work of Muñoz recalls the searches of architects like Rem Koolhaas in his projects for the firm Prada (top) or the house in Bordeaux (below).

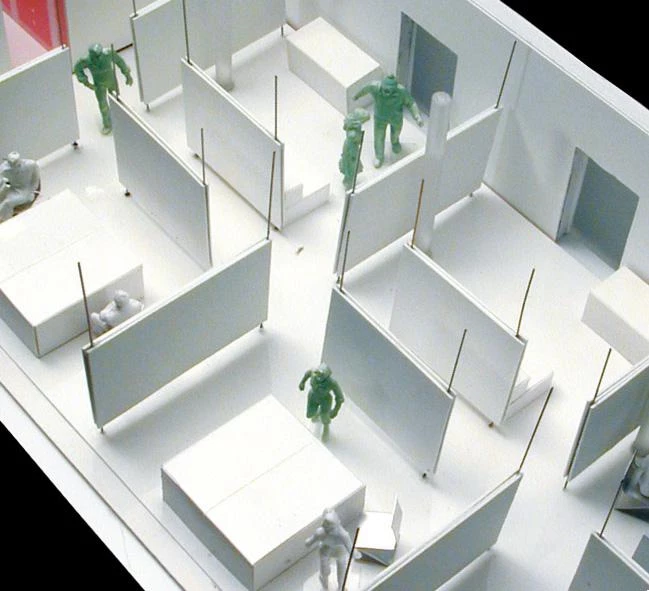

On the opposite pole, both artistically and symbolically, is Juan Muñoz’s installation at the Tate Modern, a colossal masterpiece of an artist who is celebrated more in the international arena than in the Spanish scene, yet represents the country’s impatient vitality better than the run-of-the-mill stiltedness of Felipe de Borbón’s residence or the archaic daintiness of the Porcelanosa Connection. With the illusionist architectures and enigmatic figures through which Muñoz provides a sculptural metaphor of schizophrenia and a spatial image of our dislocated societies, the Baroque scenography of Double Bind is an effective summary of an artistic career that has now sadly been interrupted, a layered and silently speculative reflection about contemporary anomy, and a successful confrontation with the dimensional and multitudinarian challenge of today’s spectacle-museums. With its empty elevators in constant motion, the geometrical trompe l’oeil, its desolate rooms and indifferent persons, the work of Muñoz bangs on our intelligence and sequesters our emotion even more efficiently than his Plaza of 1996 (the famous “installation of the Chinese” in Madrid’s Palacio deVelázquez) and with a better understanding of the Tate’s huge foyer than his predecessor in The Unilever Series, the sculptress Louise Bourgeois.

Admirably in dialogue with the building refurbished by the Swiss partners Herzog & de Meuron, Juan Muñoz’s installation refers as well to the architectural explorations of another hyperactive cosmopolite, the Dutch Rem Koolhaas, with whom he shares an ambitious penchant for the large scale, a theatrical way of manipulating sections, and the ambiguity of working in the critical cracks of art and commerce.Whether the translucent floors of the Rotterdam’s Kunsthal, the mobile platform of his Bordeaux house, the wide pit of the Guggenheim of Las Vegas or the immobile labyrinths of the projects for the fashion firm Prada, the spaces built by Koolhaas are inhabited by a multitude of foreshortenedcharacters that are not difficult to relate to the self-withdrawn figures of Muñoz, closer to the anodyne anonymity of the boxes of figurines constructed at the scale used by the architect in his models, than they are to the social-realist severity of George Segal, the painstaking lyricism of the Madrid artists Antonio and Julio López or the sensationalist provocation of the Chapman brothers.

Installed in the building remodelled for the Tate by Herzog & de Meuron, the work of Muñoz recalls the searches of architects like Rem Koolhaas in his projects for the firm Prada (top) or the house in Bordeaux (below).

The schizoid spaces of Muñoz and Koolhaas portray a dislocated society, but are at the same time scenes of a collective hallucination that one is hard-pressed to look straight at. After all, it is easy to write that with the disappearance of the sculptor the art of our times has lost a singular protagonist, and architecture a privileged interlocutor. But eightdays before Muñoz passed away, so did the British astrophysician Fred Hoyle, to whom we owe the knowledge that we are made from the dust of dead stars, and this scientific evidence echoes in the four photographs in which the artist in 1995 staged his disappearance to fabricate a consoling metaphor. Split between metaphysics and spectacle, the same country that begins the schoolyear resumes the soccer league. Zidane has said that he is having trouble playing up to par, and suddenly we understand what our problem is. We are having trouble playing up to par. And so are the architects of princes. Only Juan Muñoz, dissolved into star dust, has finally attained his level, absent and exact in the immobile figures of his mercurial, illusory architecture.