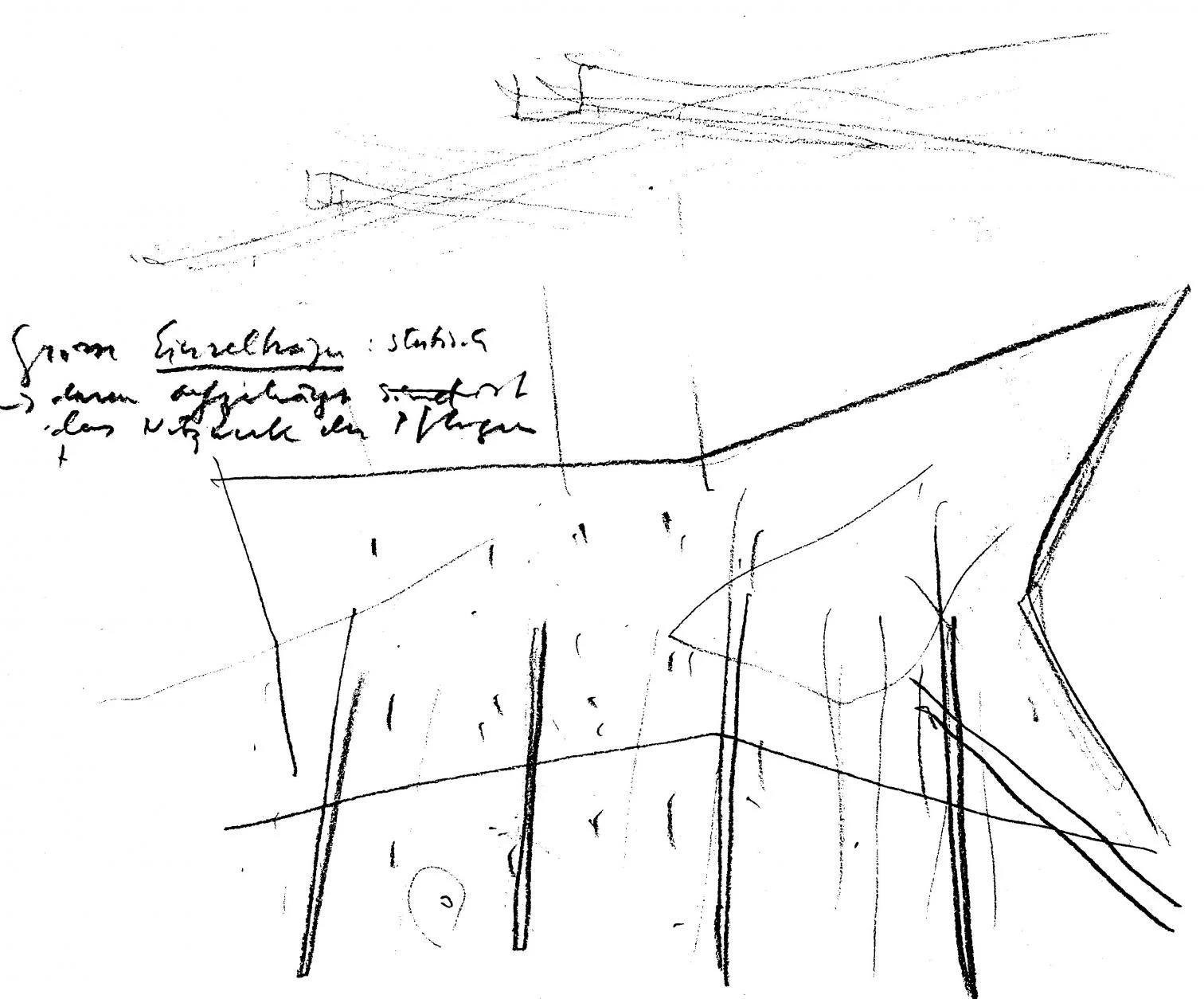

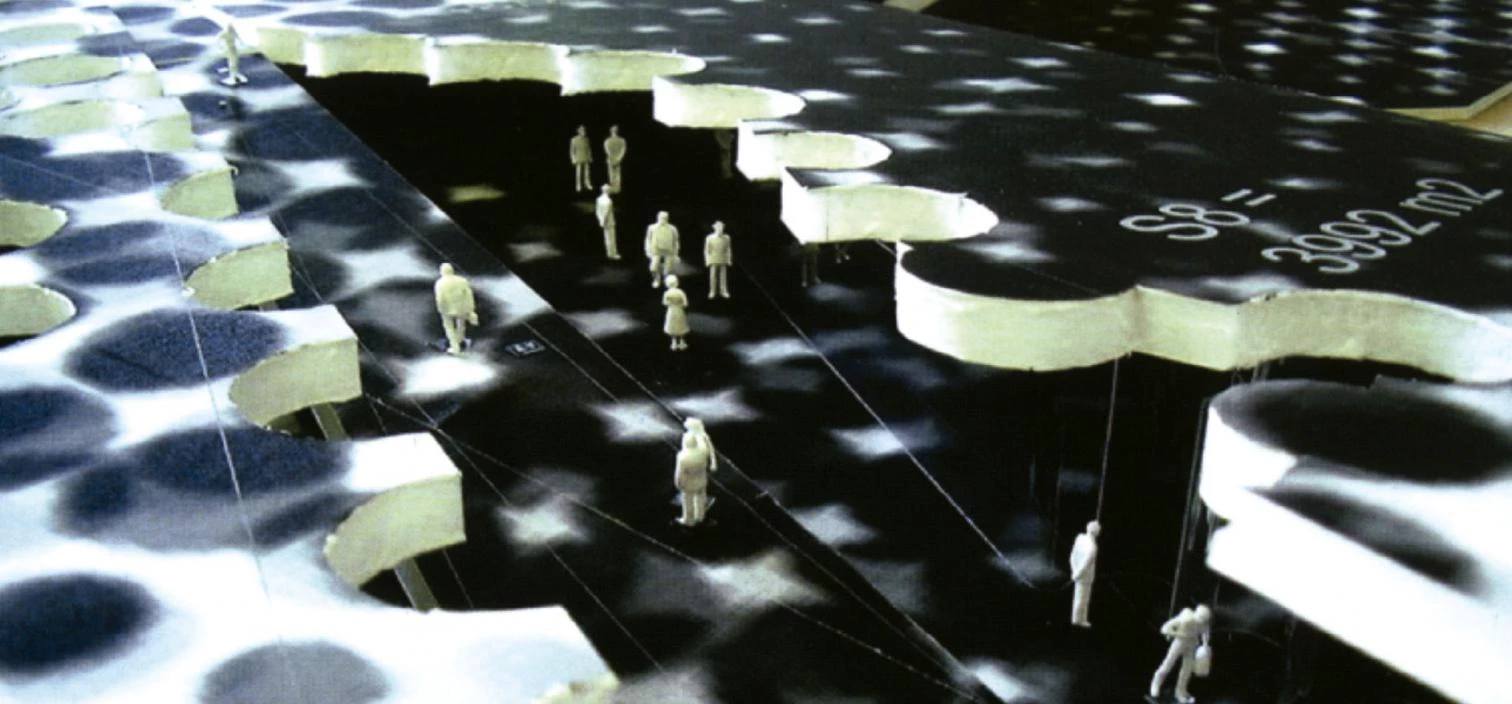

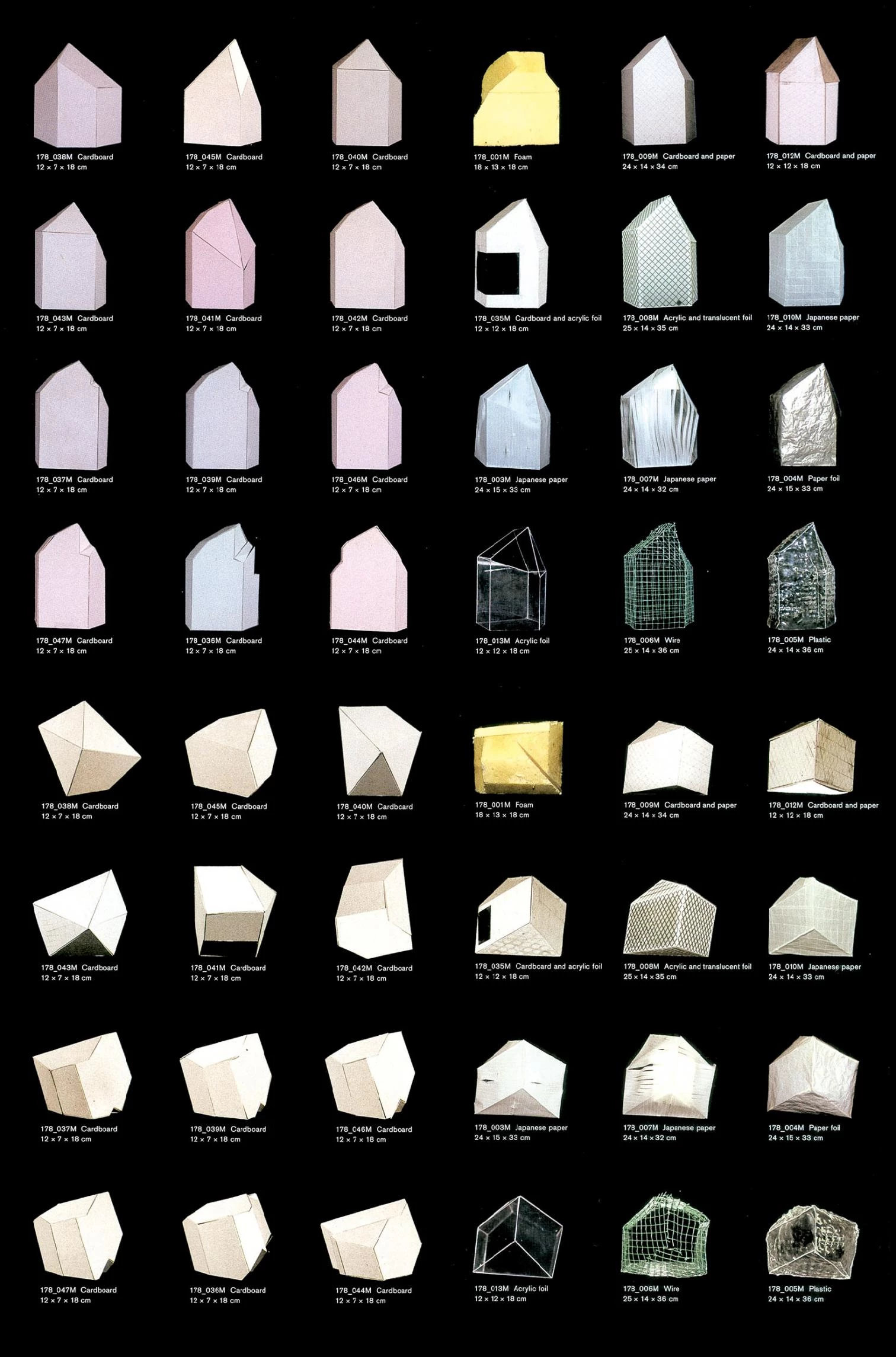

The catalog is entitled Natural History, but the work of Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron presents itself in Montreal like nature without history. Unlike the accelerated time of general history, the slow time of the natural world composes a still landscape: geological foldings and the evolution of the species occur so gradually as to provide an almost timeless backdrop to the convulsive shakings of human societies, and this is what gives an oxymoronic perfume to the archaic term ‘natural history.’In the exhibition of the Canadian Center of Architecture (CCA), over eight hundred models from the Basel studio are interspersed with fossils and insects, Chinese rocks, ethnographic objects, photographs and daguerreotypes, toys, product catalogs, sculptures, and paintings, forming an enor-mous Wunderkammer that tries to create the atmosphere of curious fascination that characterized Renaissance and Baroque chambers of wonders, and the fervor for encyclopedic collections that was typical of 19th-century museums.

At the end of the nineties, the vitreous and vegetal star of Ricola’s marketing building in Laufen was a turning point in the evolution of the practice.

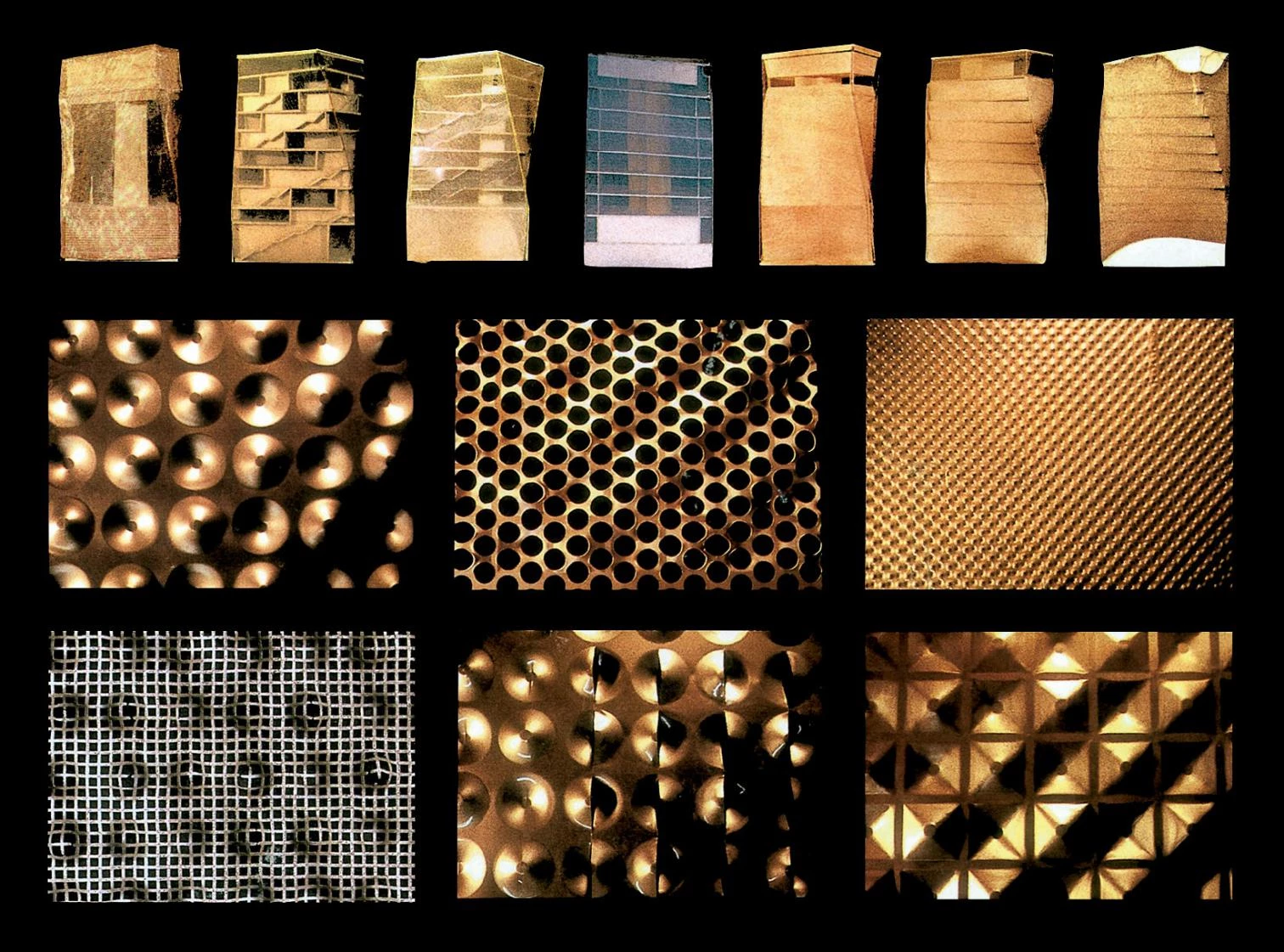

In dialogue with contemporary works of Beuys, Federle, Giacometti, Judd, Richter, Smithson or Warhol, but also in visual conversation with paleontological and entomological pieces, the models of Herzog & de Meuron – ranging from the small preliminary proofs to enormous fragments of final mock-ups – are so diverse in materials and shape that they must be contemplated like a generous heritage of formal experiments capable of nourishing a whole generation of architects. Whether serigraphed concrete panels or copper bandages, basalt gabions or convex glasses, each expressive innovation of theirs provokes a progeny of emulations. As with the mature Le Corbusier – to whom they have gradually gotten closer, with the objet type giving way to the objet a réaction poétique – the extraordinary fertility of their formal imagination has made the Basel partnership a formidable artistic engine of the architectural scene.

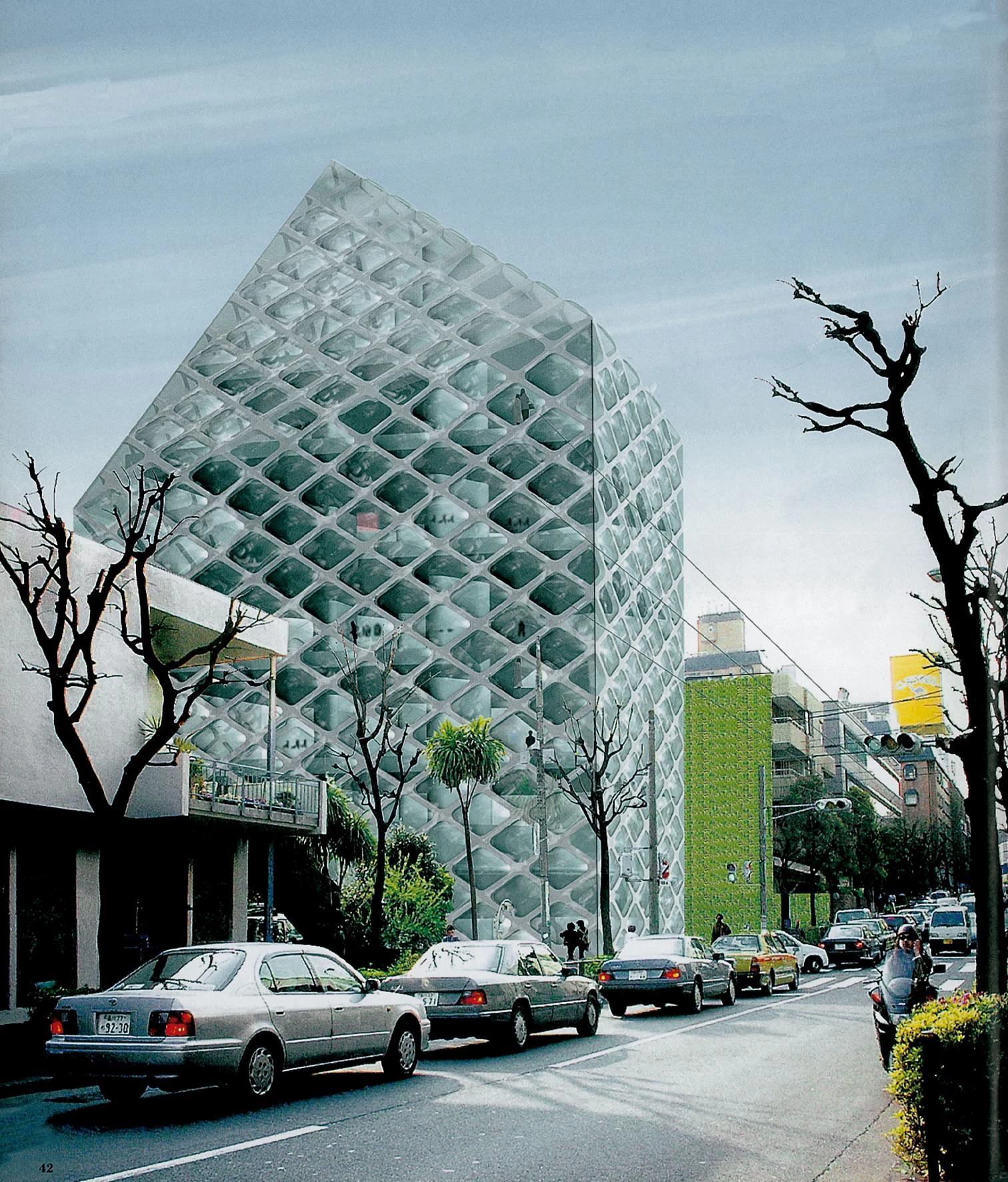

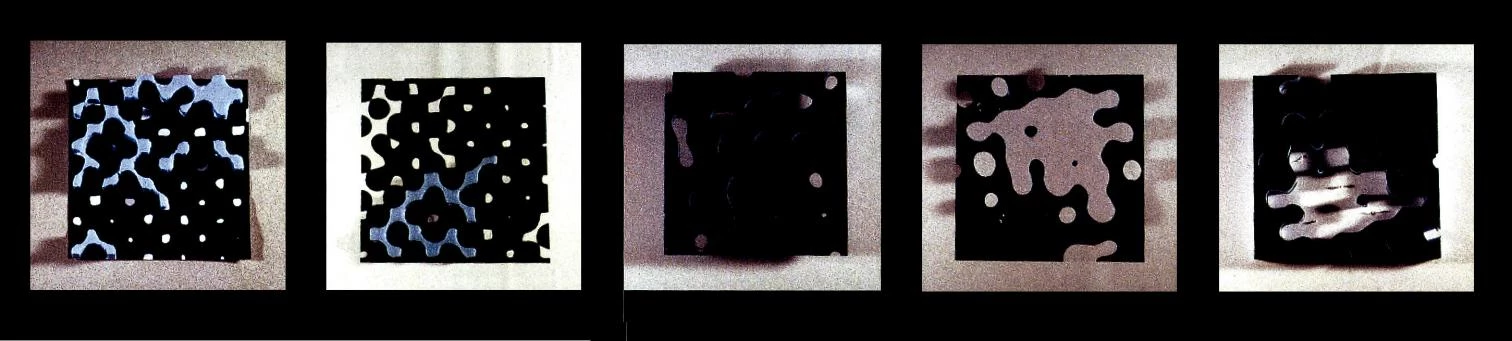

The pierced slab of the Santa Cruz de Tenerife quay blends images of geological strata and blemished skins; and the crystallographic prism of the Prada Tokyo shop recalls Taut’s utopias and Hugh Ferriss’s visions.

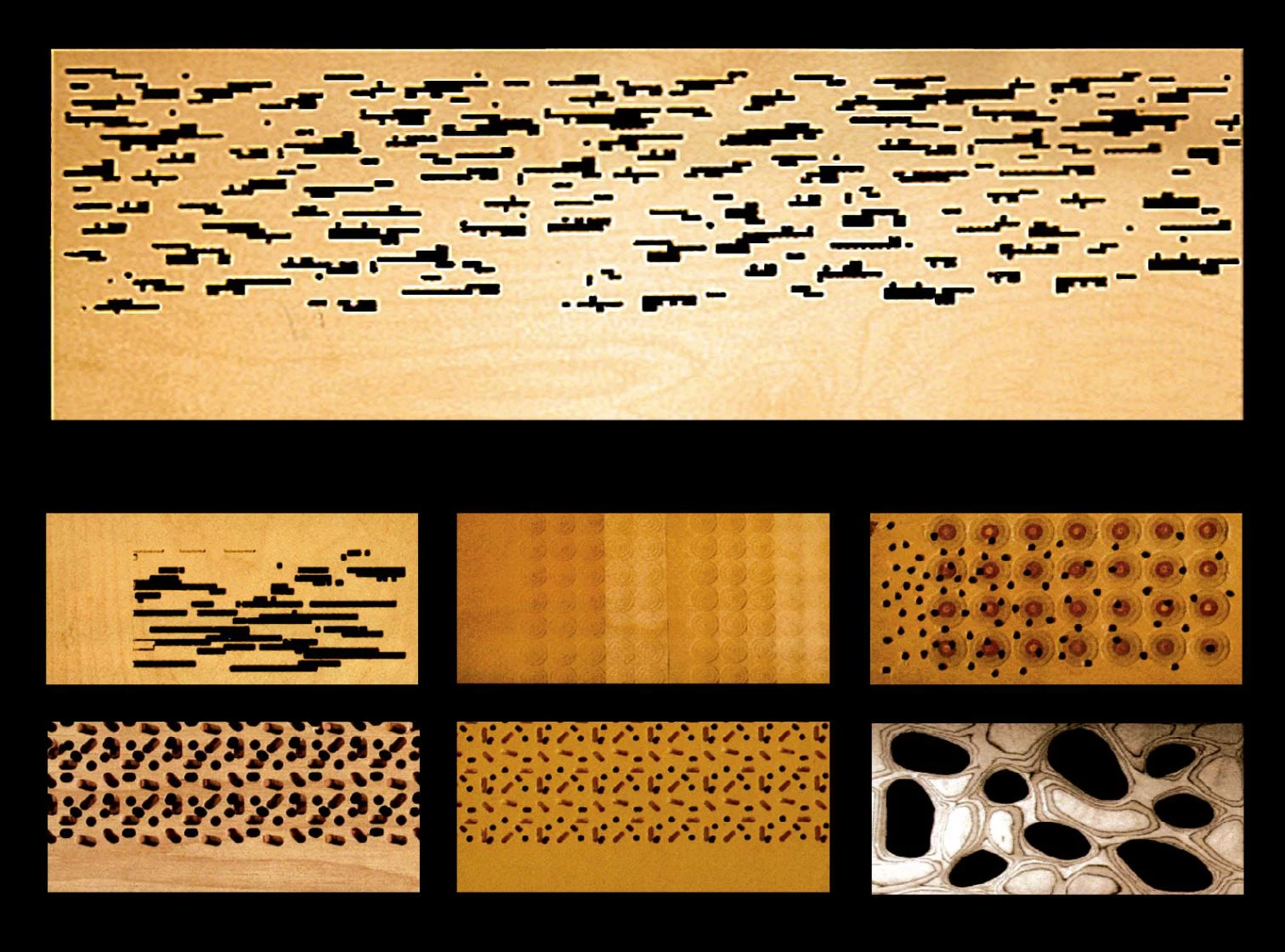

More alchemic than organic, and grouped with equivocal taxonomy in an encyclopedia of objects closer to the laboratory than to the archive, the projects are juxtaposed with nature but with the caution of one who fears the vacuous simulation of the amusement park or theme zoo, with its rocks and trunks of painted plaster. Thus the earth strata are given geometric perforations, the crystals are softened with jewellers’bubbles, and the wrinkled pelts are tattooed with pixelated images, somehow in the manner in which pop art used dots. This volcanic explosion of geological and biological references avoids literal analogy by dyeing nature with the artifice of invention, but it cannot avoid a palpitation of romantic empathy vaguely derived from Louis Sullivan’svegetal ornaments or BrunoTaut’sAlpine architectures. Objets trouvés revealing ‘the hidden order of nature’ and manufactured objects eloquently expressing the deliberate order of making, this pharmacopoeia of forms ends up offering poèmes alpestres where Goethe mixes with Rudolf Steiner’s anthroposophy, and where Novalis joins the visionary dances of Monte Verità.

The hundreds of models displayed at the Canadian Center for Architecture are presented in taxonomical sequences that evoke the boxes of mineral rocks or insect showcases of the collections of natural history museums.

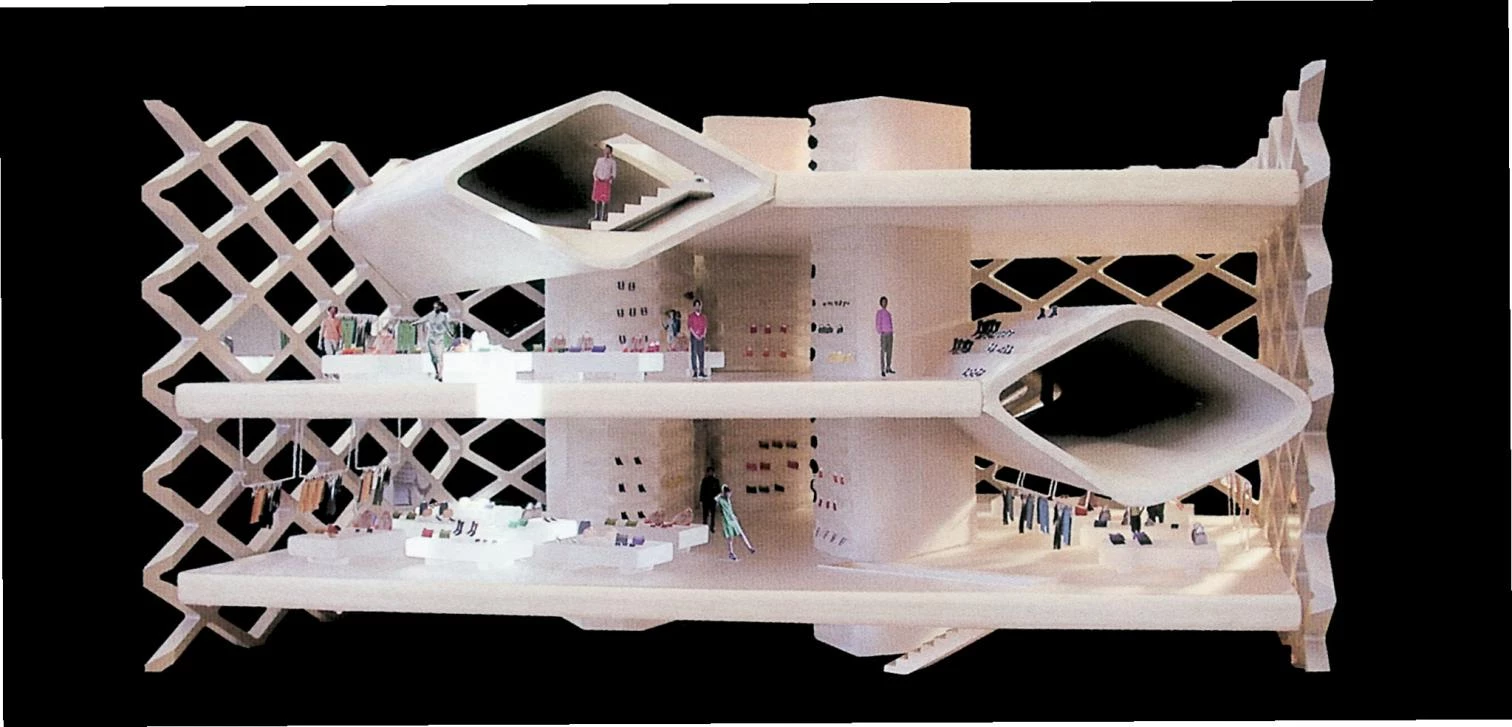

With sensual violence and rough lucidness, the work of Herzog & de Meuron has gone from minimum to maximum without faking solutions of continuity, ever so naturally pulling the thread that connects Ricola’s soothing herbal candies to Miuccia Prada’s bags and shoes, without changes of context and dimension interrupting the consistency of their emotional exploration. In the wake of the office building for Ricola – a glass star that dissolves in reflections to fuse with the vegetation that covers and surrounds it – the Swiss partners have yielded a flood of disturbing forms that subject the retina to a hypnotic abrasion. Some, like the nearly finished Prada store in Tokyo – a crystallographic prism, geometrically defined by urbanistic guidelines, that combines the Utopian splendor of Taut’s glass pavilion with the somber expressionist edges of the skyscrapers imagined by Hugh Ferriss –stretch the elemental language of their master, Rossi, to a scale that makes it necessary to wrap the building with a tight rhomboidal mesh which holds the glassy mass in place like a painful corset, halfway between the wire cages in the stone gabions of the Dominus winery and the tense cords oppressing the feminine torsos of Hans Bellmer’s pho-tographs. Others, like the new wharf in Santa Cruz de Tenerife – a plaque perforated by the aleatory sequence of a photograph translated into a scheme of dots – fabricate rare landscapes that merge the geological echoes of arbitrary layers with the exact wounds of circular cuts and the dark fuzzy stains that, closer to a skin disease than to a feline fur, blemish the epidermis of the square.

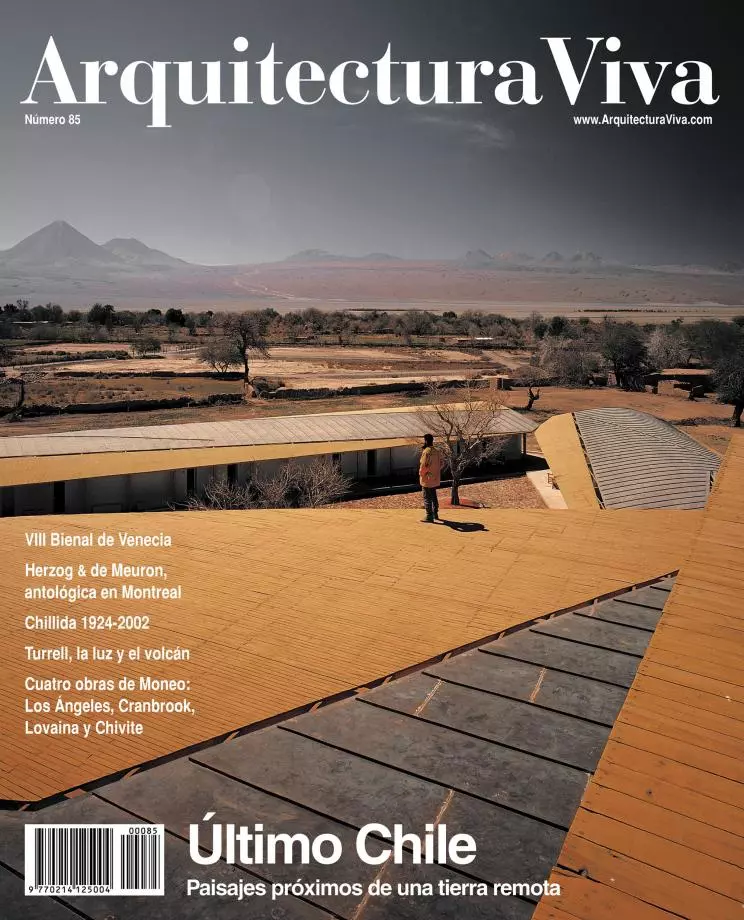

The New Link Quay, Santa Cruz de Tenerife

Of course some will see the Prada building as nothing but a capricious and mediatic bijoux at the service of a fashion multinational, cushioned with the repeated bulges of a wall of screens in a store selling TV sets, undecided between an opulent, gem-incrusted jewelry case and the blinking installations of Nam June Paik, theatrically luminescent like the Basel stadium, and as ethereal as the evanescent halo of Munich’s. And there are also those that will judge the Tenerife dock as an anecdotal wink at Lichtenstein or Vasarely paintings, at once pop and op art, that with the ironic use of the processes of mechanical reproduction is able to recreate the is-land’s volcanic topographies through a gruyère of cartoon craters not too different, to be sure, from the large, floating, worm-eaten slab of Barcelona’s sculptural Forum of Cultures. Nevertheless, as much in the Tokyo blisters as in the Tenerife punches shines a dark light that situates these projects under the sign of Saturn, and illuminates their interpretation of nature with a silent, melancholy gleam, carving out of natural history a nature deprived of history and time. In Basel one can see The Crucifixion of Mathias Grünewald, a visionary and somber canvas that, in his poetry book Nach der Natur, the late W.G. Sebald chose to juxtapose with the Arctic adventure of the enlightened naturalist George Wilhelm Steller, a researcher of the Siberian flora who perished in that empty and frozen immensity: the cold vertigo of art and science from nature illuminate with lucid darkness the building from nature that these architectures rehearse.

Museum and Cultural Center, Santa Cruz de Tenerife

New De Young Museum, San Francisco