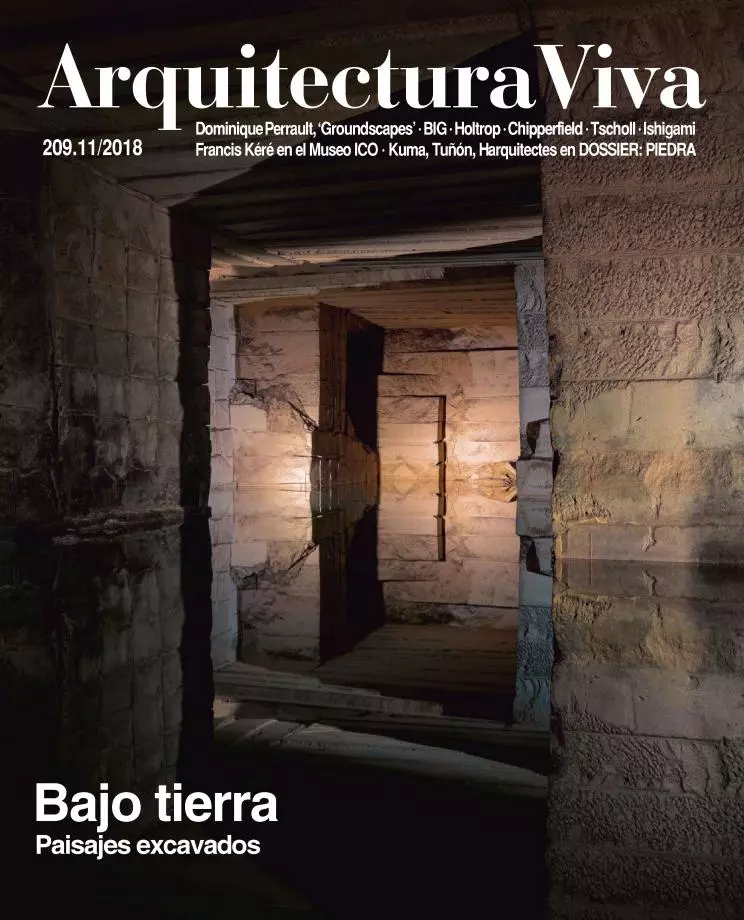

The dark light of hidden spaces is fascinating and confusing. On one hand, it is hard not to succumb to the oneiric attraction of enigmas, and the descent to the depths of the earth is a symbolic itinerary of initiation that captures us with its mineral magnetism, turning crypts and basements into primeval caves that hide and reveal what is secret. On the other, the rationalist approach of modernity tries to chart those cavities without being captured by the fuzzy fog of a perception altered by the shadows of myth, and describes catacombs or bunkers as necessary shelters from the violence of the world, extreme precincts rather than redoubts of charm. The negative space of excavated architecture is both theatrical and ominous: stage in penumbra of ceremony or ritual, and dark refuge that protects from persecution or calamity.

The neologism that lends this note its title gathers an extraordinary variety of cases, including the functional adaptation of geological accidents, abandonded quarries, or obsolete fortresses, as well as the fresh excavation of the ground for the construction of subterranean architectures. Inspiration often comes from primitive or vernacular traditions, which have left us many examples that respond to necessity, but also from the classical repertoire, be they Roman cryptoporticoes or mannerist caves, where the type range encompasses from the spaces created by the infrastructural logic of foundations and retaining walls to the fanciful recreations of the forms of nature for spectacle or for leisure. What we have proposed to call cryptoarchitectures are therefore not so much a type, but rather a very large family of subjects.

Though each case deserves its own approach, and many of these architectures are admirable in their concept and hypnotic in their aesthetic, the popularity of buried constructions as ecological alternatives must not set aside their drawbacks. If in the urban context growing downwards is often more advisable than growing upwards – and indeed more than growing sidewards –, in rural areas the integration in the landscape and the thermal inertia supplied by excavated architecture must necessarily be counterbalanced by the indelible traces it leaves on the ground and the alteration of the water table. In many instances light constructions are more sustainable than buried ones: those that sit on the land like insects rather than those that drill into it like moles. And still we are carried away by the dark light and nutritious warmth of that fertile womb.