Nasty Comparisons

Parc Güell by Antoni Gaudí

Harold Bloom maintains that critical judgment boils down to better, worse, or equal. What if we were to apply such criteria to the match between Madrid and Barcelona? At the risk of charicaturizing, here are some nasty comparisons.

Cerdá or Arturo Soria? According to Françoise Choay, Ildefonso Cerdá founded a discipline, urbanism. Any contender pales beside such credentials. To boot, Barcelona’s Eixample is more intelligent and more generous than Madrid’s Salamanca quarter. Yet the Plan Cerdá does not differ much from the contemporary Plan Castro of Madrid. Although we must acknowledge the reach of his Teoría General de la Urbanización, Cerdá was more a systematizer than an innovator. In contrast, even granting that it came much later, Arturo Soria’s Ciudad Lineal was an intellectual adventure whose enlightened avant-gardeness is a forebear of the British garden-city and Soviet dis-urbanist utopias. And its eventual failure denoted the foretold ruin of modern dreams.

Gaudí or Palacios? In this department Barcelona wins the day. Granting Gaudí’s exceptional and archaic genius puts him on a different plane, even Domènech i Montaner is a more stimulating architect than Palacios. Modernismo as a whole has a candor not to be found in the academic rhetoric of Madrid. Antonio Palacios was a quarter of a century younger than Domènech, yet his architecture was older. There is more daring in the interior of the Café-Restaurant – built when Domènech was not yet modernista and Palacio was but a child – than in the entire oeuvre of the Madrid – based Pontevedran. If Domènech had not had so many political and social interests to take his time, if he had been as devoted to architecture as Gaudí, perhaps we would now not know which of the two Catalans was the greater architect.

Sert or Zuazo? Encyclopedias allot more space to the former, and maybe with reason. But the Barcelona city planner, architect and pedagogue Sert has the advantage of a long American career. In a close examination of his work, the stubborn veneration of Le Corbusier can become exhausting. From the canonical rationalism of early Republican projects to the Mediterranean modernity of his mature works, the radical Sert now seems orthodox in his disciplined fidelity to novelty. Working class and bourgeois housing may not be comparable, but the schematic plan of Casa Bloc blurs beside the typological intelligence of Casa de las Flores. Though fifteen years the Catalan’s senior, Zuazo tackled the building and the city with a more contemporary rigor. If on the scales we add the engineer Eduardo Torroja’s concrete American career. In a close examination of his work, the stubborn veneration of Le Corbusier can become exhausting. From the canonical rationalism of early Republican projects to the Mediterranean modernity of his mature works, the radical Sert now seems orthodox in his disciplined fidelity to novelty. Working class and bourgeois housing may not be comparable, but the schematic plan of Casa Bloc blurs beside the typological intelligence of Casa de las Flores. Though fifteen years the Catalan’s senior, Zuazo tackled the building and the city with a more contemporary rigor. If on the scales we add the engineer Eduardo Torroja’s concrete shells, the balance tips in favor of Madrid’s brick rationalism, which has a gravity that Barcelona’s white modernity lacks.

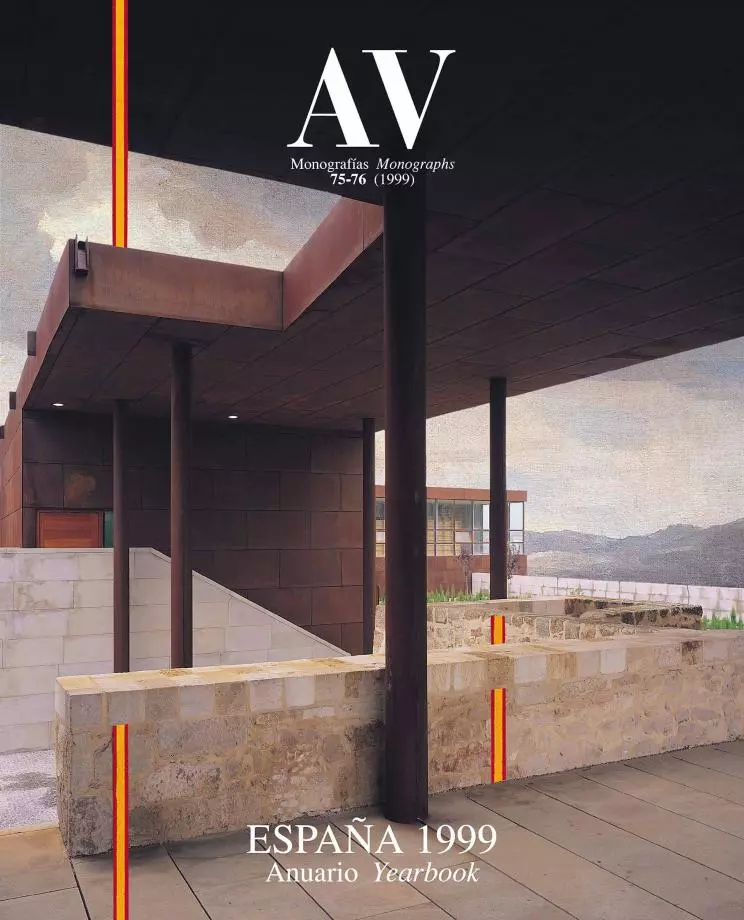

The extreme and archaic genius of Gaudí (above, Parc Güell) and the historical awareness of Moneo (below, Merida’s Roman Museum) are the chronological extremes of the dialogue between Barcelona and Madrid.

Merida’s Roman Museum by Rafael Moneo

Coderch or Sota? José Antonio Coderch had a privilege which Alejandro de la Sota did not: the advantage of diffusing his work through photographs by Francesc Catalá-Roca. It is known that the critical fortune of many architects rests in their photographers, and for an entire Barcelona generation, Catalá-Roca was a happy luxury. In any case, Coderch undeniably stands out among his Catalan contemporaries. The panorama around him, however, was leveled by the circumstances of the Spanish Civil War, whereas Sota’s Madrid scene bristled with talent, from Cabrero and Fisac to Oíza or Molezún. In this context, Sota stood out as a seductive personality who fascinated students with his laconic defence of the most extreme functionalism: his myth was built by disciples, not by photographers. If Coderch left images, Sota’s best legacy are words.

Bofill or Moneo? True to the delocalized character of contemporary practice, the most cosmopolitan of Barcelona’s architects and the most international of Madrid’s have each carried out significant works in the city of the other. Rafael Moneo transformed the School of Barcelona during his teaching stint there, and has given the Diagonal a colossal block that is a masterly lesson on urbanity. Ricardo Bofill, in turn, has endowed Madrid with a convention center that is the most important work ever to be carried out by its Town Hall, which has also contracted him as a soother for the city’s urbanistic malaises. Bofill’s intuitive self-confidence cannot be easily compared with Moneo’s cultivated approach, and many critics would simply refuse to put them on the same plane. However, the fact that Barcelona – without generosity – has known how to use Moneo’s talent, while Madrid – without criteria – has only known how to tap Bofill’s aplomb, says much of the current situation.

In this last comparison, all the more nasty considering how the splendid achievements of Olympic Barcelona have highlighted the coarse mediocrity of recent Madrid, the different statures of the architects eloquently illustrate the opposed moods of the cities. As the capital of Spain, Madrid is better able to attract talent from far beyond, as the provincial origins of so many Madrid architects prove. But perhaps because it belongs to the Castile that makes and unmakes men, or because of the uprooting inevitable in crowded metropoli, Madrid will never learn to make as much from its human resources as a better woven and more domestically knitted Barcelona.