Mastership too comes in tones. Although our late-romantic upbringing makes us prefer major masters, minor masters are more interesting when it is times, not so much persons, that we wish to comprehend. Lacking ego, minor masters are better at striking the tone of the age. Luis Bellido was a minor master. Trained in the pragmatic times of eclecticism, he had no style or language of his own. Like many architects then, he connected function to character and character to ornament, so every building of his, without ceasing to be exceptional, abided by the demands of decorum. Such stylistic flexibility was the result of a compliance with codes that architects now find hard to understand, indoctrinated as we are in the modern yet archaic idea that architecture is necessarily the fruit of innovation. That is why we feel so far from the type of architect represented by Bellido: talented professionals who had extremely fertile and important careers.

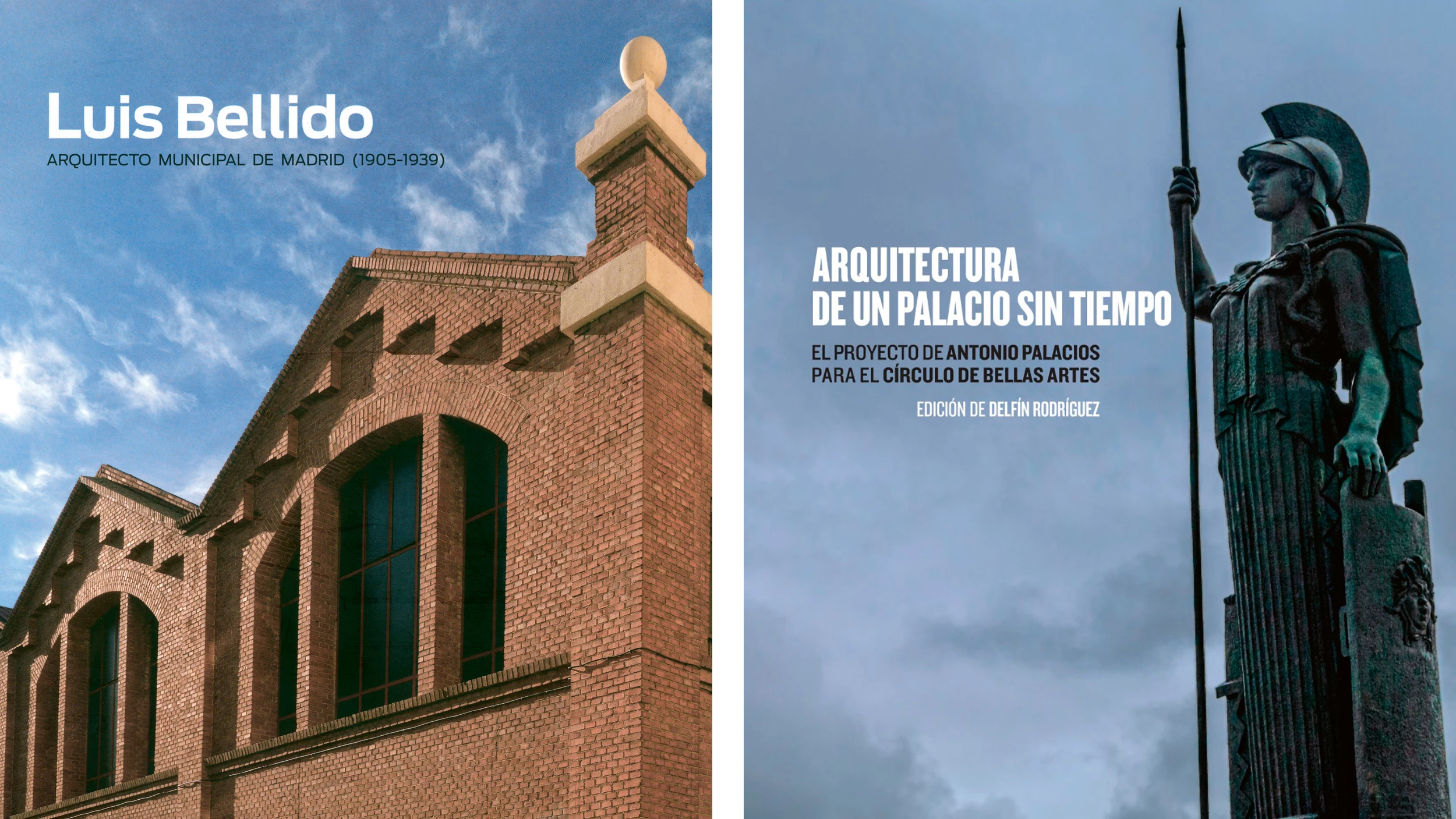

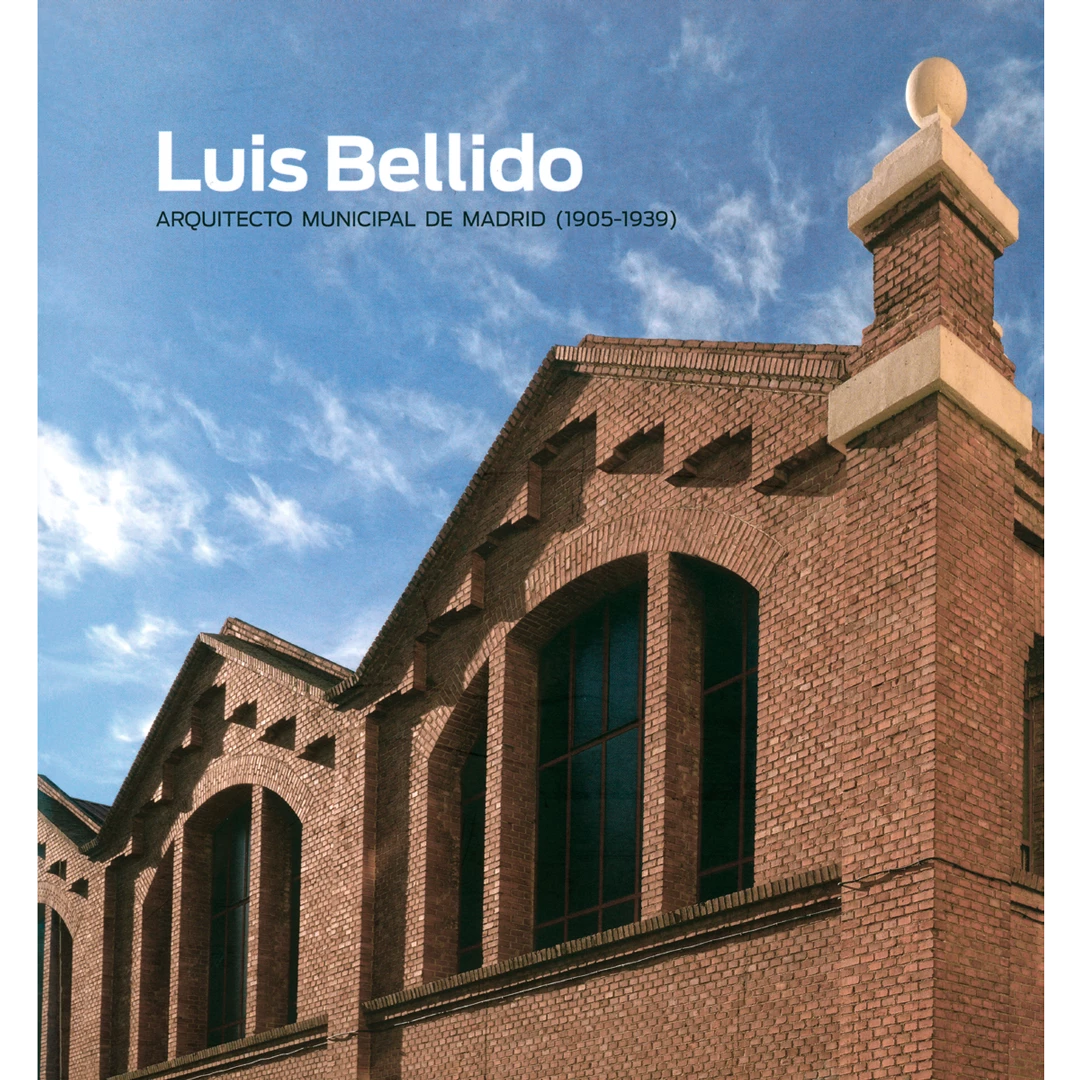

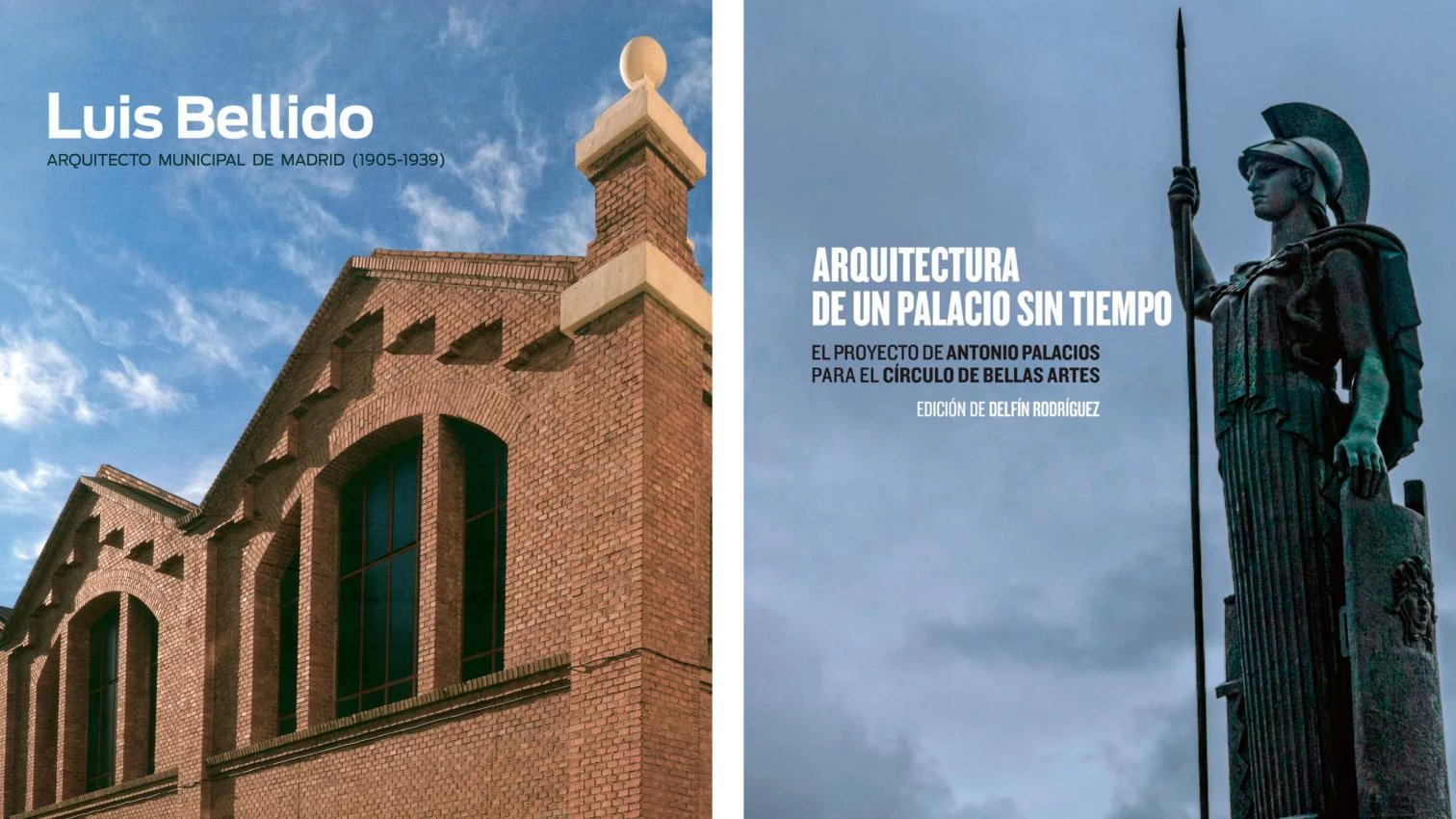

Taking stock of Bellido’s importance is the purpose of ‘Luis Bellido: Municipal Architect of Madrid (1905-1939),’ an exhibition on view at the Conde Duque Cultural Center, in the Spanish capital. It comes with a catalog bearing the same title. Abounding in original documents and featuring splendid essays, it is the most complete monograph on Bellido to date.

The book not only leads us through the personal life and career of the architect born in 1869 – his years in Galicia and Asturias, his professional anointment in the capital, his induction into the Royal Academy of Fine Arts – but also gives us the heartbeat of the period, particularly the pulse of the city he served as municipal architect for years: a growing Madrid eager for renewal as well as for monumental representation and hygiene reform. Here were two aspirations Bellido successfully met: bourgeois monumentalism through buildings in the city’s gridded extension, with their mix of Parisian and Spanish references; and hygiene reform through more utilitarian constructions, where the architect materialized a Mudejar rationalism, stripped but decorous, whose quality is vouched for by projects like the Tirso de Molina Market and the Abattoir.

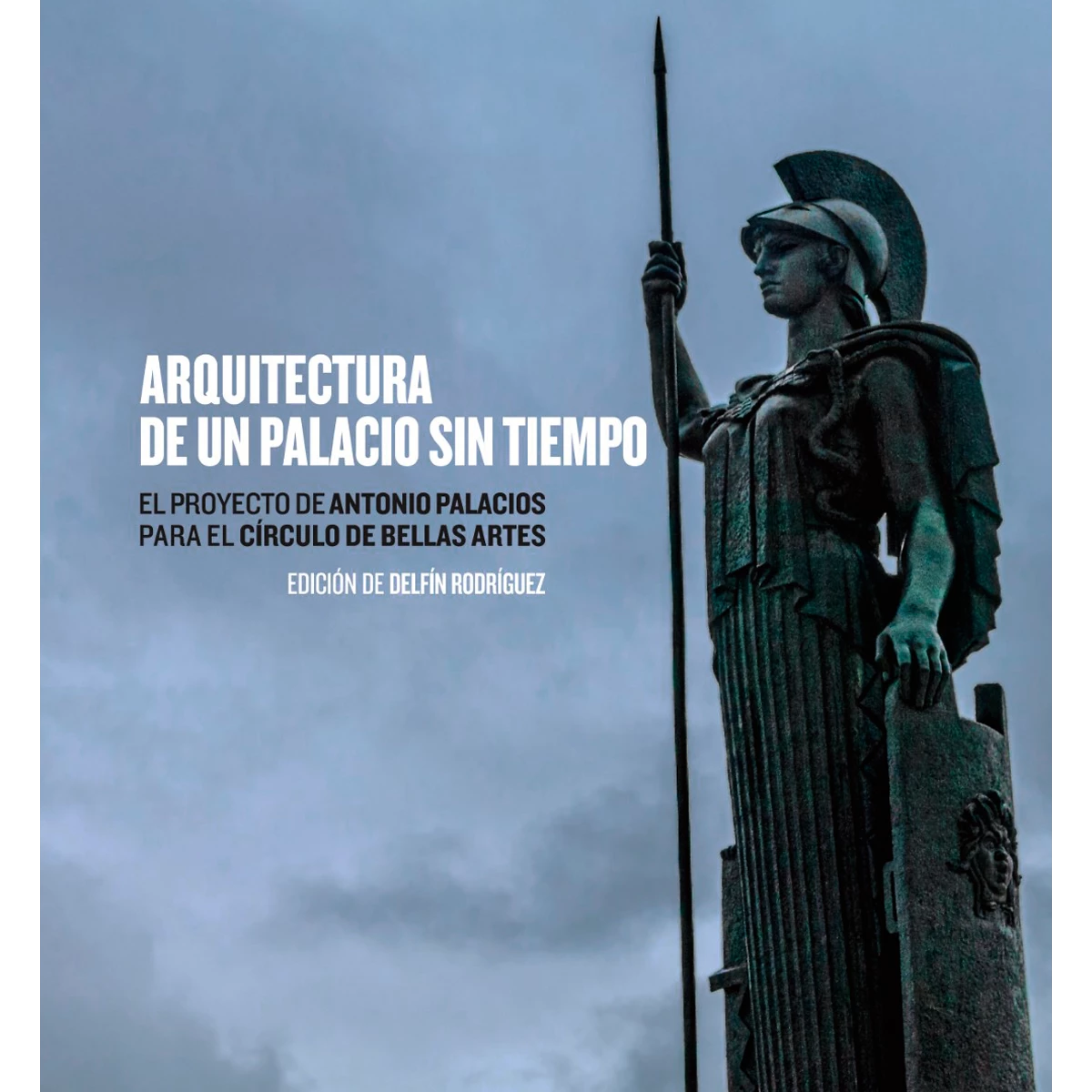

In the bustling capital of the early 20th century Bellido coincided with a younger talent, a major master whose language would stand out for a long time: Antonio Palacios. If Bellido’s contribution to Madrid was important, even more so was that of this architect in possession of an astonishing knack for forms and a rare ability to connect with the bourgeois spirit. Palacios did this especially through edifices along the Alcalá-Gran Vía axis: the Communications Palace, the Río de la Plata Bank, and the Fine Arts Circle.

The latter is the subject of a volume produced for its centenary. It tells the story of the competition and the subsequent development and execution, also digging into specific aspects, from the building’s symbolic role in the context of a rising metropolis to the iconography generated by a construction that was controversial from the start and to which, not in vain, Federico García Lorca dedicated a sonnet.