Art colonizes life, but life resists the violent invasion of art. The modern Utopia of everyday beauty has given way to the postmodern fiction of exceptional beauty, which is ill-suited to the placid landscapes of anonymous life. Yet contemporary architects, ignoring the silent nature of housing, choose to use the residential project to cry out in the name of art, and though it is impossible not to hear them, not everybody cares to listen. Shrill like the arias of Bianca Castafiore on the dreamy afternoons of Moulinsart Castle, the plastic screams of sculptural apartment buildings pursue beauty in inopportune settings, inducing us to follow Hergé’s Captain Haddock in his discreet flight from the diva. Opera has no place in the siesta, and a love for art does not require one to live inside an art object.

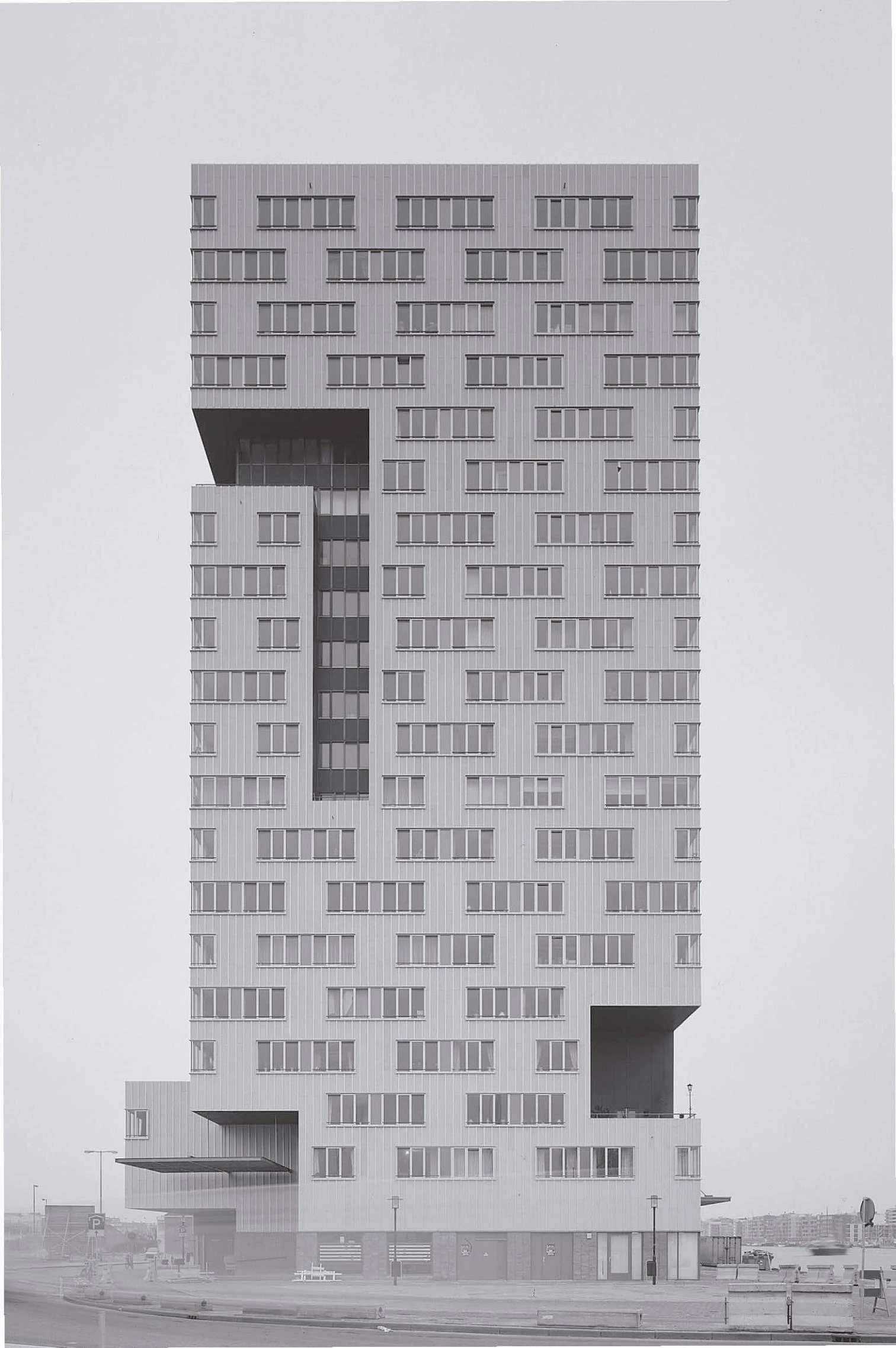

Bordering on the bay of Amsterdam, the tower designed by Jan Neutelings and Michiel Riedijk stands as an urban landmark, dominating a port area that is being transformed into a residential zone.

At best, these sculpted pieces serve as urban landmarks in desolate zones, or as singular residences where the facile poetry of form makes up for the arduous prose of density. It must be said that, of course, when they proliferate, the soloist voices inevitably become indistinguishable in the jubilation of a cacophonous, chaotic choir. But as long as this does not happen, the towers and blocks of the architectural haute couture manage to reconcile the modesty of their domestic purpose with the esthetic ambition of their authors, and rise on the confusing outskirts as self-withdrawn, enigmatic fragments of a more clear-cut world, in such a way that even the random disorder of their interlockings comes from a painstaking mathematical combinatorial analysis.

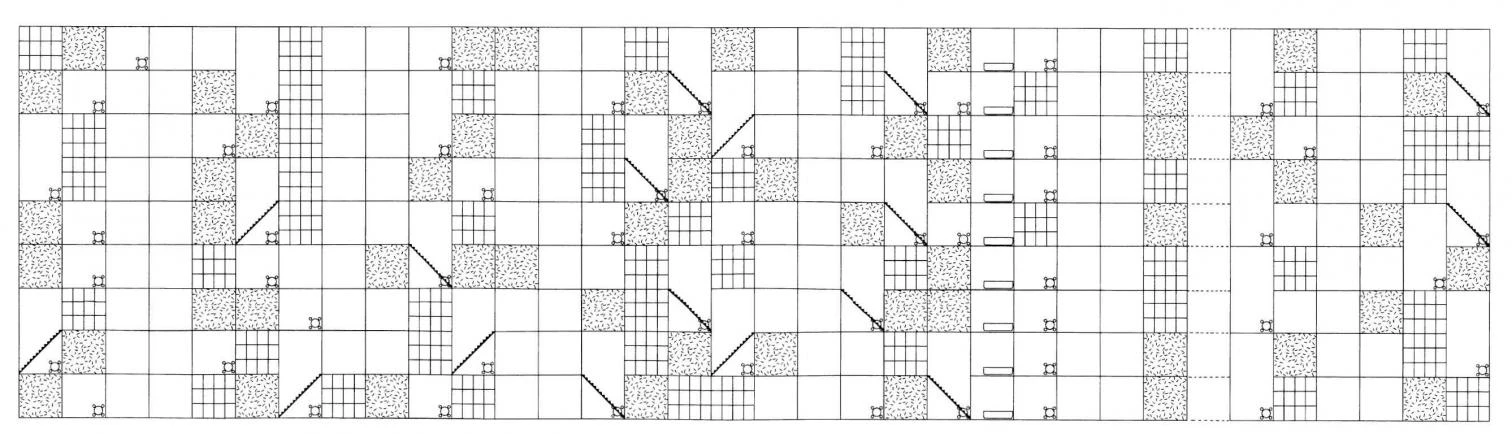

On the edge of the bay of Amsterdam, the 20-story tower erected by the Belgian Willem Jan Neutelings and the Dutch Michiel Riedijk acts as a monument in a dock area that is becoming residential. Working from their shared Antwerp and Rotterdam studios, the two young architects carve out arbitrary fissures in a tall abstract prism wrapped by aluminum-joined fibercement panels and bands of windows placed diagonally from one another. Inside this neutral-looking box, 68 dwellings of 20 different types are arranged in such a way that no two are alike, without such extreme variety doing anything to break the categorical and metaphysical aplomb of what is a hermetic monolith. Rainbeaten and windswept, in this gray and exact tower reside both the poetry of desolation and the anxiety of the existential.

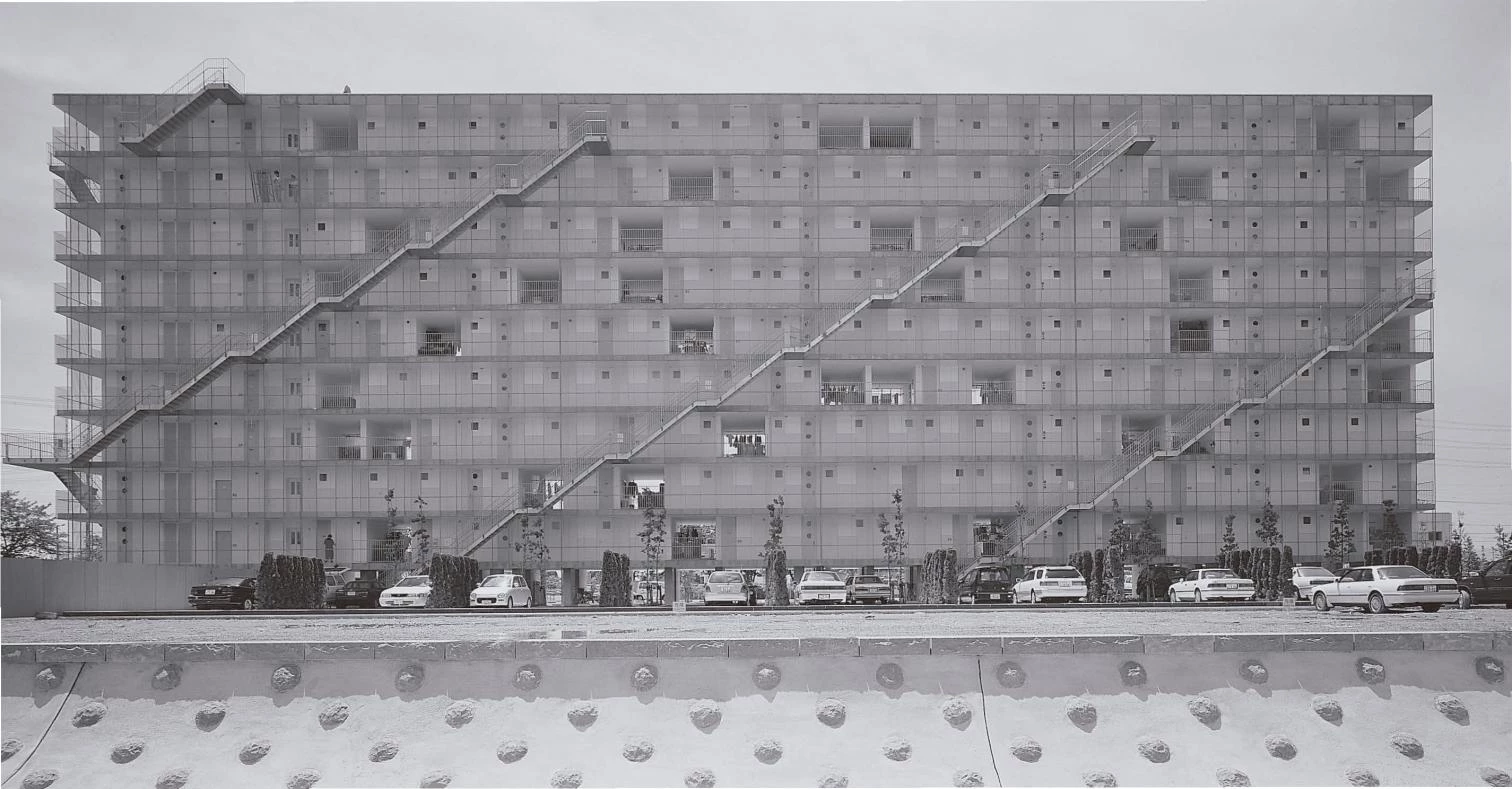

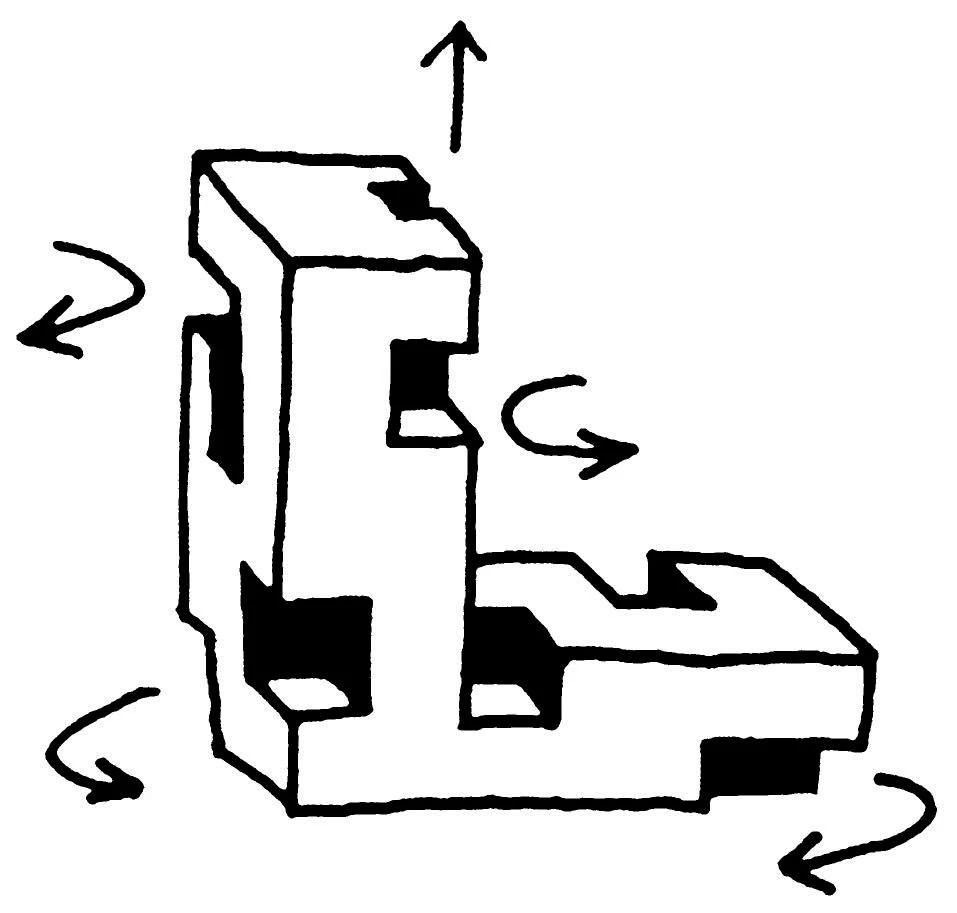

On the other side of the planet, the Japanese Kazuyo Sejima has subjected the conventional forms of housing to similar esthetic and geometric reflections. Within a complex of 420 social dwellings in the prefecture of Gifu, distributed by the veteran Arata Isozaki among four young women architects (the others being Elizabeth Diller of the United States, Christine Hawley of Great Britain, and Akiko Takahashi of Japan as well), Sejima’s project tries to relieve the functional misery of the colossal block of concrete, glass and steel through the same resources being used by her European counterparts: the abstraction of the image, the minimalist refinement of detail, and the selective positioning of voids. These gaps make for a large variety of unit dwelling types in the interior, while marking the facade with a musical rhythm that serves as a background to the psalmodic melody of the fire escapes stretched across the galleries with indifferent unanimity.

Large scale returns to residential architecture in towers like that of Claus & Kaan in Groningen (above) or of Wiel Arets in Amsterdam (below), breaking with the horizontal silhouette of Dutch cities.

The Dutch tower and the Japanese block resort to the sculptural fissure and the musical perforation, respectively, to mold powerful external images while orchestrating the inevitable diversity of apartment types inside. One alternates windows, and the other staircases, to create the diagonal composition needed to soften the all too predictable verticality or horizontality, as the case may be. And both take refuge in combinatory modules to create objects of extreme precision, abstraction and elegance. Never mind that we are being made to inhabit a sculpture or a music score. The occupants of these self-withdrawn, neutral buildings will use the speedy lifts and interminable corridors with distracted, gray indifference, but in the small cells of these huge geometric anthills, the tenacious disarray of life shall continue to represent episodes of the human comedy, removed from art and from its frigid fictions.

Eighty years ago now – in the small German city of Weimar, incidentally this year’s European culture capital – a group of artists and architects founded a school that would endeavor to reconcile art with life. At the close of the century we look upon this adventure of Walter Gropius in Weimar as a heroic and fertile failure, and contemplate the mythical dream of the Bauhaus with the tender irony that tends to be reserved for eternally pending revolutions. But Goethe’s aspiration to a “more beautiful humanity” is also still a pending matter, and that was even longer ago.

Between Art and Life

The nineties have witnessed the destruction of the taboo of the large residential development. During the boom of the sixties, huge apartment towers and blocks went up and gave rise to massive social problems having to do with overcrowding, the isolation of the individual and the anonymity of these new quarters, some of which had to be demolished.

The traditionalist reaction of the seventies was to arrest this metropolitan phenomenon through the avoidance of megatowers and macroblocks, now symbols of the inhuman city of savage capitalism or bureaucratic socialism. But the past decade has rescued the highrise apartment building for societies that are already irremediably fragmented anyway, societies which without nostalgia have given up on the ideal of a friendly residential community.

A good example of such historic inflection is provided by horizontal Holland, where public housing operations used to be careful to avoid the excesses of height and scale, but where apartment towers are now proliferating all around – legitimized, to be sure, by a sculptural refinement that renders them exquisite containers of self-withdrawn lives.

In Japan, Kazuyo Sejima turns to the abstraction of forms, the refinement of detail and the selective perforation of spaces in order to lend character to this block of social housing in Gifu (cover & below).