Magdalene College Library, Cambridge (United Kingdom)

The Irish philosopher Edmund Burke interpreted the spirit of England in the 18th century, and the Irish architect Níall McLaughlin has done the same in the 21st. Born in Geneva in 1962, educated at University College Dublin, and with an office in London since 1990, his search for timelessness through deference to context and material perfection has made him a favorite of the Oxford and Cambridge colleges, for which he has drafted numerous projects. Burke’s Whig liberalism preferred the continuity of habits to revolutionary ruptures, and his defense of “common opinions, common affecttions, and common interests” is well illustrated with buildings that blend modern excellence into historic campuses. In his Reflections on the Revolution in France, the philosopher expressed his political program with an architectural language – “I would not exclude alteration either; but even when I changed, it should be to preserve... I would make the reparation as nearly as possible in the style of the building” –, and this ‘guarded circumspection’ inspired by ethical principles rather than due to a weakness of character would serve well to describe the oeuvre of Níall McLaughlin.

While remaining attentive to ancestral Ireland – from the lyrical lightness of the cloistered garden for Alzheimer patients in Dublin, to the ceramic and muscular poise of the rugby center in Limerick –, the father of Iseult and Diarmaid has raised his perhaps most memorable works in the intellectual heart of England, and this circumstance seems appropriate for someone who reconciles practice and theory, as the Jencks Award recognized in 2016, which celebrated both the architect and the professor at the Bartlett, UCLA, or Yale. The exact drum of the Bishop Edward King Chapel at the Ripon Theological College is an elliptical enclosure that through stone, concrete, and larch is placed at the service of light, and the Sultan Nazrin Shah Centre extends Worcester College with an auditorium and dance studios that use limestone and oak to create a material still life in an arcadic landscape. But these Oxford works, like the contextually refined and urban Jesus College in Cambridge, are just a few of the many completed in these two mythical campuses, symbolically crowned with the Stirling Prize awarded in 2022 to the New Library at Cambridge’s Magdalene College.

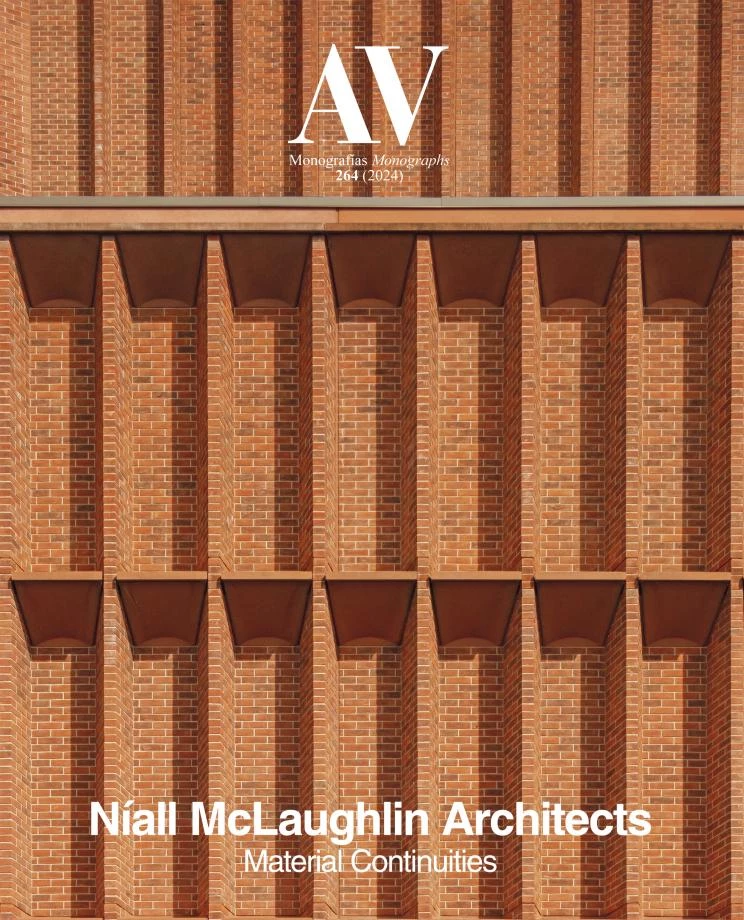

The ceramic musicality of this geometric forest of books, evocative of Tudor architecture with its pointed roofs and inspired by the Richards Laboratories of Louis Kahn in the rhythmic expressiveness of its chimneys, certainly deserves separate commentary, because its romantic classicism allows returning to Burke after exploring the territories of Semper and Ruskin. The political philosopher published in 1759 A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful, an aesthetic treatise where among other things he deals with the size, proportion, and function of buildings, as well as the light or the color in them, and I dare suggest that this ‘physiological sensibility’ is no stranger to the pleasure that comes from the exquisite construction, extraordinary palette of materials, and yearning for permanence of the works of McLaughlin. The Magdalene College Library shows a plaque with the Latin motto ‘Faber sum,’ and that classical reference to the one who makes or builds recalls the impossibility of separating the Homo sapiens from the Homo faber, and of dissociating concept and matter in the intellectual and sensitive work of this Irishman in England.

Bishop Edward King Chapel, Cuddesdon (United Kingdom)