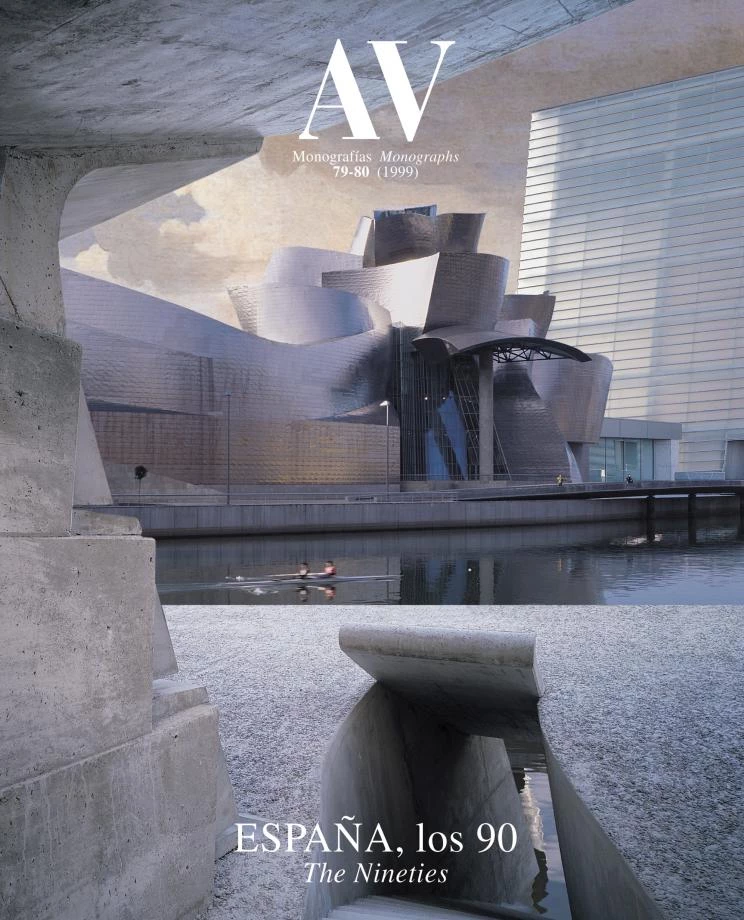

Barcelona’s Two Souls

By summoning foreign and local architects, Barcelona achieves a successful blend of the urban cultures of Europe and America.

Barcelona is Spain’s most European city. If it perseveres, it might also become the most American. Meanwhile, the city celebrates its two souls by simultaneously inaugurating a very European museum designed by an American and a very American marina built by Catalans.

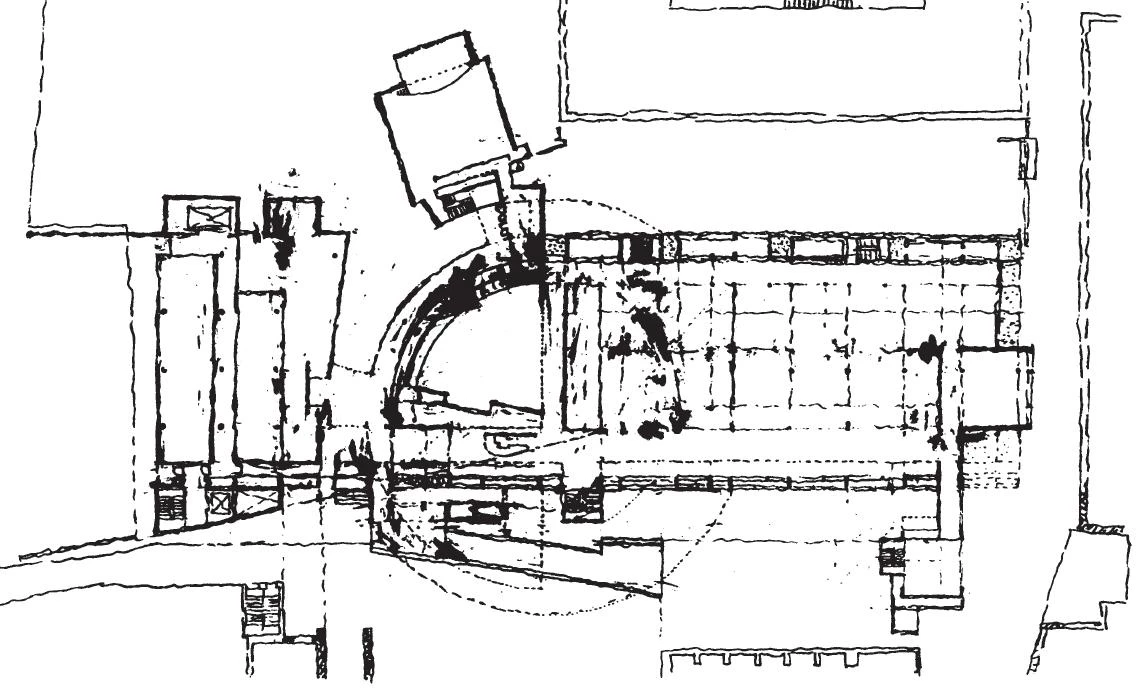

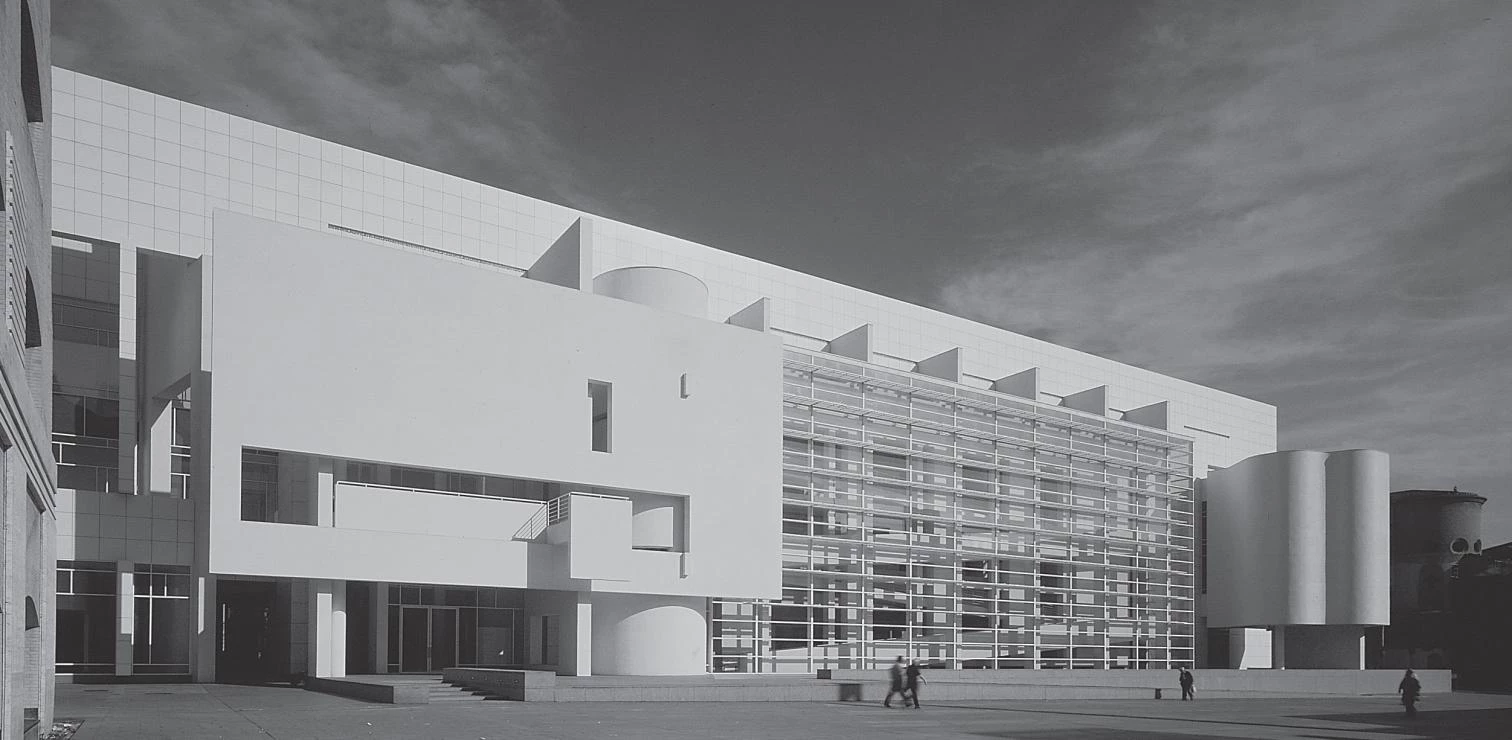

The Museum of Contemporary Art, a white luminous ship by Richard Meier in the ancient labyrinth of the Raval quarter – a deteriorated sector of the city’s historic core with narrow streets and decaying tenements, densely inhabited by an impoverished population of immigrants – was shown to the Barcelonese in April, to reopen definitively in November with the collection installed.

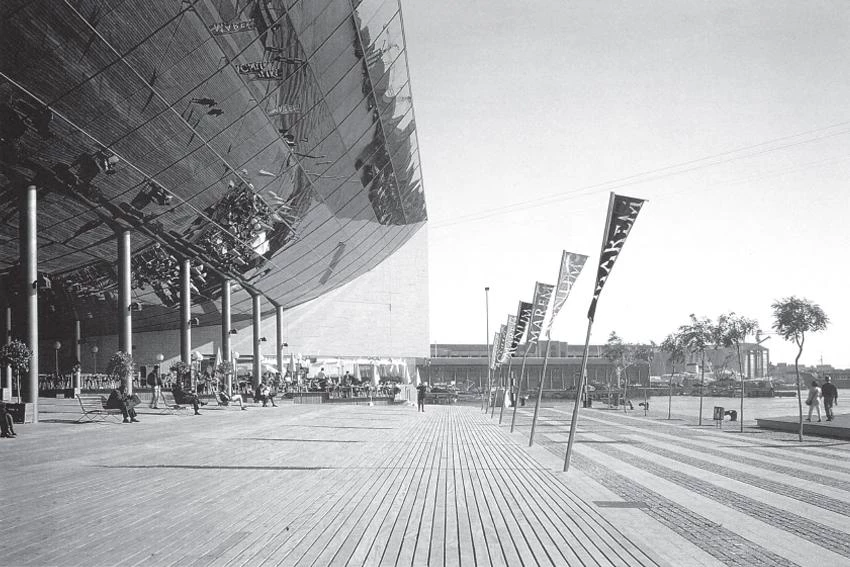

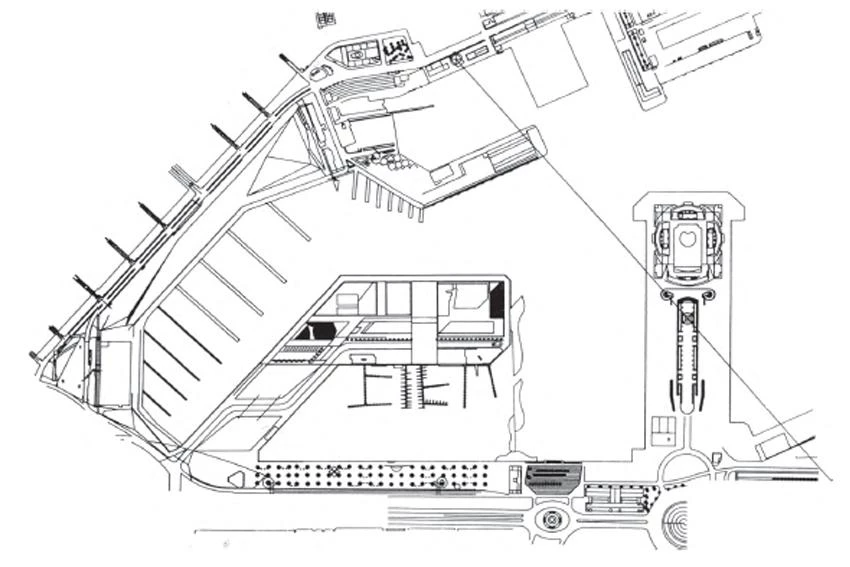

The commercial and recreation complex of Port Vell began to take shape with the opening in September last year of the controversial and lyrical footbridge designed by Helio Piñón & Albert Viaplana, which connects the Rambla to the Moll d’Espanya. Multicinemas and a huge commercial center – the `Maremagnum’ – by the same architects are now rising over this, besides an Imax cinema by Jordi Garcés & Enric Sòria and a giant aquarium – Europe’s biggest – designed by Robert & Esteve Terradas, whose forthcoming summer opening will wrap up the port complex.

Clear-cut volumes, legible circulations, careful execution and Corbusian language: true to expectations, the Museum of Contemporary Art of Barcelona is a dazzling Meier.

Two Complementary Operations

Meier’s museum is, above all, predictable. “I give what is expected of me,” the architect likes to say, and this is exactly what the people of Barcelona and Mayor Maragall – who commissioned him the project ten years ago over dinner in New York – have gotten; clear-cut volumes, easy-to-read circulations, meticulous execution and Corbusian language: the physical and symbolic clarity of a washing machine. Some critics have chided him for its dazzling interiors, for the blinding whiteness of its enameled skin, or for its excessive sculpturing; but this is surely what Barcelona was buying.

Similar to Paris’s Pompidou in its urban function – to refurbish a historic center through the regenerative influence of a great cultural center – the MACBA is European also in the purist formal language it uses: a tribute to the twenties avant-garde that Meier learned at Cornell University from his teacher Colin Rowe (winner this year, by the way, of the RIBA Gold Medal), to whom he has remained stubbornly faithful. Actually we could at this point consider Meier European, since with the exception of the artistic acropolis he is building for the Getty Foundation in Los Angeles, his latest buildings –the Canal+ headquarters in Paris, the City Hall and Central Library in The Hague, or the Stadthaus in Ulm – are all in Europe.

A complementary and symmetrical operation on the opposite end of the Rambla, the Port Vell complex is part of a dynamic effort to colonize the coastal fringe through the substitution of commercial or recreation uses for obsolete harbor functions, an undertaking which has been described in political rhetoric as the process of “opening Barcelona to the sea.”

In other places of the maritime edge the city has entrusted the design of new commercial buildings to American architects, and thus the interventions of SOM’s Bruce Graham, who was in charge of the slender cross-braced tower of the Hotel des Arts; the Californian Frank Gehry, whose glum fish rises at the foot of the same hotel; and I.M. Pei’s partner Henry Cobb, whose Trade Center has yet to be completed. But at the Moll d’Espanya, three Catalan couples – most particularly Piñón & Viaplana, authors of the masterplan, the footbridge and several buildings – are responsible for this new and disconcerting fragment of the city, which is American in its concept and relaxed volumetry and functional pragmatism, and European in the extreme avant-gardism and abstraction of its language.

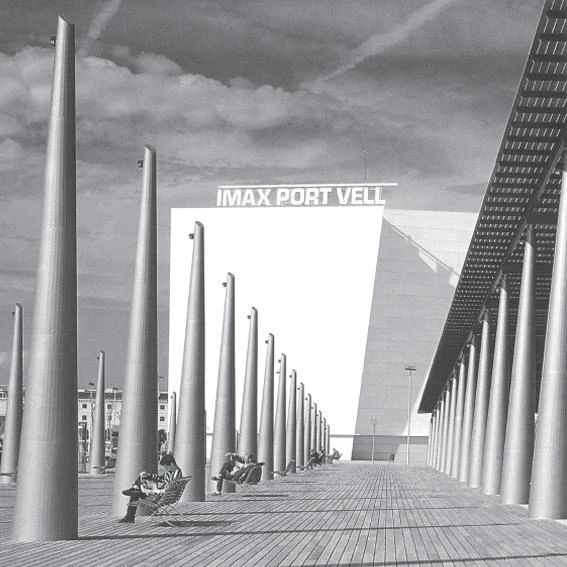

As at the Hilton Hotel of Barcelona, Piñón & Viaplana have transformed convention into exception, dressing the obese and vulgar body of commercial leisure with a smart suit, possibly with the peevish attention of a tailor forced to sew for boors, and definitely with a keen awareness of the schizophrenia of the matter. Thus, if in the footbridge-turned-wooden-beach discretion rules over necessity, in the huge commercial center and in the walkways if the dock and depured constructive aesthetic makes up for the massive triviality of their functions, using even the misfortunes and pentimentos of the construction process to dress a bulky merchandise with refined design. Similarly, Garcés & Sòria enclose their voluminous and spectacular cinema in a neat crisp box, its geometric whiteness shunning the futuristic figuration that is usual in these cases, and even the aquarium of the Terradas brothers hides behind austere and opaque concrete in a similar refusal to build the expected glazed replica of a submarine.

At Port Vell, Piñón & Viaplana have garbed the vulgar body of commercial leisure with an elegant suit. On the same site, Garcés & Sòria have enclosed the Imax cinema (below) in a crisp elegant box.

If the Raval museum avoids Gothic historicism or artisanal local color by rising like a nautical and radiant bride in the midst of a degraded quarter, Por Vell flees from fisherman or sailor picturesqueness by sprinkling the wharf with its bachelor origami, mechanical and light. The high culture of art museums and bookshops on one hand and the popular culture of Imax and shopping malls on the other, at opposite ends of the Rambla, provide the same Sunday leisure to flâneurs, tourists and families, in a happy crossbreeding that will eventually unite the bride with her bachelor friends.

European or American?

During the recent electoral campaign there was much discussion about the European or American nature of Barcelona’s urban project. The two models were presented as being mutually exclusive, with clearly negative connotations attributed to the American one. But in a process of modernization it is difficult to draw the line between continents. In the dawn of its democracy, Spain was a fervently Europeist as it was suspicious of the American friend; now, ten years after joining the Union and in the threshold of a Spanish presidency, enthusiasm for Europe has waned as much as mistrust toward the United States, and this has produced a set of attitudes which are more ambivalent and nuanced than ever.

Unlike Madrid, which imports everything American without digesting it – a posthumous and vulgar skyscraper by Minoru Yamasaki, the Picasso Tower; a frustrated hotel by Eisenman close to the Reina Sofía Museum; or two troubled leaning towers at the end of the Castellana by two partners, Johnson and Burgee, in terminal crisis –, Barcelona carefully chews the American experience, lining it with design and obligating it to keep up appearances: even the very Spanish El Corte Inglés – which like Galerías Preciados, its rival up to recently, brought to the peninsula, via Cuba, the north American concept of department-store sales – has had to don a cultivated skin in order to look on to the Plaza de Catalunya. What in Madrid is raw, violent and excessive becomes casual and placid in Barcelona, softened by the provincial prudence and educated traditionalism of a city that respects itself, a city which understands that in order to be very European it must also be a bit American.

Nothing can exemplify this rare hybridization better than the exhibition that Barcelona’s Center of Contemporary Culture is dedicating these days to James Joyce’s Dublin, where the literary and biographic itinerary of the author of Ulysses and Finnegans Wake is reconstructed with the friendly and figurative language of Disneyland attractions. Only a city like Barcelona could have dared to stage its own particular Bloomsday on a thematic key, interpreting the most hermetic avant-garde through the most trivial of languages. But this approach, when turned around, is precisely the methodological support of its own architectural and urbanistic activity, where the everyday is decked with the avant-garde, fertilizing the popular with the intellectual, and marrying life with art. Yes, in Barcelona the bride will eventually encounter her bachelors.[+]