New Synagogue, Mainz

The word reborn- Architect Manuel Herz

- Type Religious / Memorial Synagogue

- Material Ceramics

- Date 2010

- City Mainz

- Country Germany

- Photograph Iwan Baan

Few Jewish communities can surpass the one of Mainz in importance and tradition. During the Middle Ages the city was a major center of religious instruction, and this can be traced back to a series of influential rabbis, especially Gershom ben Judah, whose teachings and legal decisions had an impact on Judaism at large. His wisdom was deemed so great that he was given the name ‘Light of Diaspora.’ The new synagogue of Mainz builds on this tradition.

Even though the building site is the location of a previous synagogue, destroyed during the Nazi era, it was my intention that the new synagogue not reference the Holocaust. Fragments of the old synagogue had been placed there in the 1980s by a previous generation. I kept them there out of respect for that decision, but it would not have been my decision. For a number of reasons, it was my very intention that the destruction of the old synagogue not be the foundation of my new synagogue. First of all, there were several synagogues of Mainz before that war, across the city. Secondly, I did not want to make the Nazi destruction a ‘co-author’ of the new design. And last but not least, the city of Mainz has literally shaped the Jewish religion we know today. This positive force had to be celebrated in my design. The Mainz chapter of the Holocaust needs to be commemorated somewhere else.

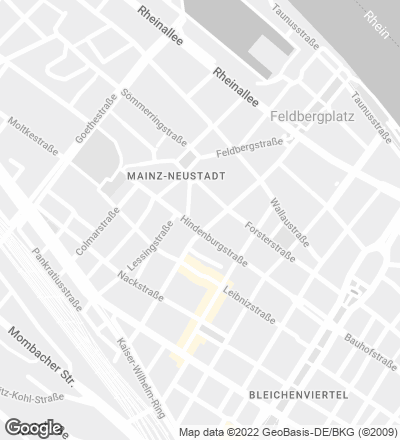

The site for the synagogue is located in a late 19th-century residential neighborhood, characterized by its perimeter block pattern. We chose to use this urban figure for the overall layout of the synagogue. The volume of the building is situated parallel to the streets and its facades are in line with the existing neighboring buildings, thus creating a contained street space. The use of the perimeter block typology for a sacral building is highly unusual, as one would usually expect a religious building to sit like a solitary volume, withdrawn from the street.

By orienting the part of the building containing the prayer hall towards the east, two squares or open spaces are created: an internal garden for the community offering room for recreation and celebration, and a public square in front of the main entrance offering an open place for the neighborhood within a densely built-up urban fabric. The absence of any kind of gating or barriers is what makes this square a truly civic space, used for everyday activities by the general public, which is rare for a religious building, especially for a synagogue, in Germany.

In the course of its history Judaism has never developed a strong tradition of building. Unlike other religions, it has not developed architectural styles that try to convey certain values and credos in spatial terms. Instead, there was text. In Judaism, writing can be seen as taking the place of spatial production. Specifically the Talmud, written after the destruction of the second Temple and the beginning of the Diaspora, can be viewed as a response to the loss of Jerusalem as Judaism’s central place, as an answer to uprootedness in general, and as an alternative spatial model. The theme of space traverses the whole Talmud, from the content of individual chapters to the dialectical techniques of the rabbis (their methods of arguing and debating), not to mention the very manner in which the text is written. Also, on the level of individual words and letters, an object quality is expressed in the writings. This object quality of writing, combined with the concept of the Talmud (which found its central place of learning in the city of Mainz) as a notion of space, informs the design of the Jewish community center of Mainz.

The facade shows the process of inscribing or carving a pattern, creating a three-dimensional surface formed with glazed ceramic tiles. The pattern is arranged concentrically around the windows, resulting in a perspectival play of dimensionality, in such a way that multiple perspectives with the windows as vanishing points emerge on the building’s facade. This spatial quality is enhanced by the green glazing of the ceramic tiles, which reflects the shifting light conditions of the surroundings by means of a wide array of hues and shades.

The interior surfaces of the synagogue are shaped by densely packed Hebrew letters forming an unreadable, almost endless, mosaic-like ornamented pattern. In certain areas this density of letters is reduced, and the text becomes readable. Piyutim (religious poetry) written by the rabbis of Mainz in the 10th and 11th centuries are carved onto the surfaces of the synagogue. In a very pure and beautiful language they tell of love for the Torah, alluding to the ‘Song of Songs’ or the events around the destruction of the community during the first crusades, and reference the central role played by Mainz in the history of Judaism. They celebrate the cultural production of Mainz, and by extension the creative power of the Diaspora...[+]

Obra Work

Sinagoga Nueva de Maguncia

New Synagogue, Mainz (Germany)

Cliente Client

Jüdische Gemeinde Mainz.

Arquitectos Architects

Manuel Herz Architects / Manuel Herz (socio partner); Elitsa Lacaze; Hania Michalska, Michael Scheuvens, Peter Sandmann (proyecto de ejecución detailed design); Cornelia Redeker, Sven Röttger, Sonja Starke (proyecto básico concept design).

Consultores Consultants

Mainzer Aufbaugesellschaft (gestión de proyecto project manager); Klaus Dittmar Architekt (dirección de obra site supervision); Harald Heims (paisajismo landscape); Arup (ingeniería estructural structural engineering); Niels Dietrich Keramikwerkstatt (fachada cerámica ceramic facade); K. Dörflinger (electricidad electrical engineering); House of Engineers (instalaciones MEP services); IBC Ingenieurbau Consult (física de las construcciones building physics); Ingenieurbüro Ingo Petry (protección contra incendios fire protection); Ingenieurgesellschaft für Technische Akustik (acústica acoustics).

Presupuesto Budget

6.000.000 €.

Superficie Area

2.500 m².

Fotos Photos

Iwan Baan.