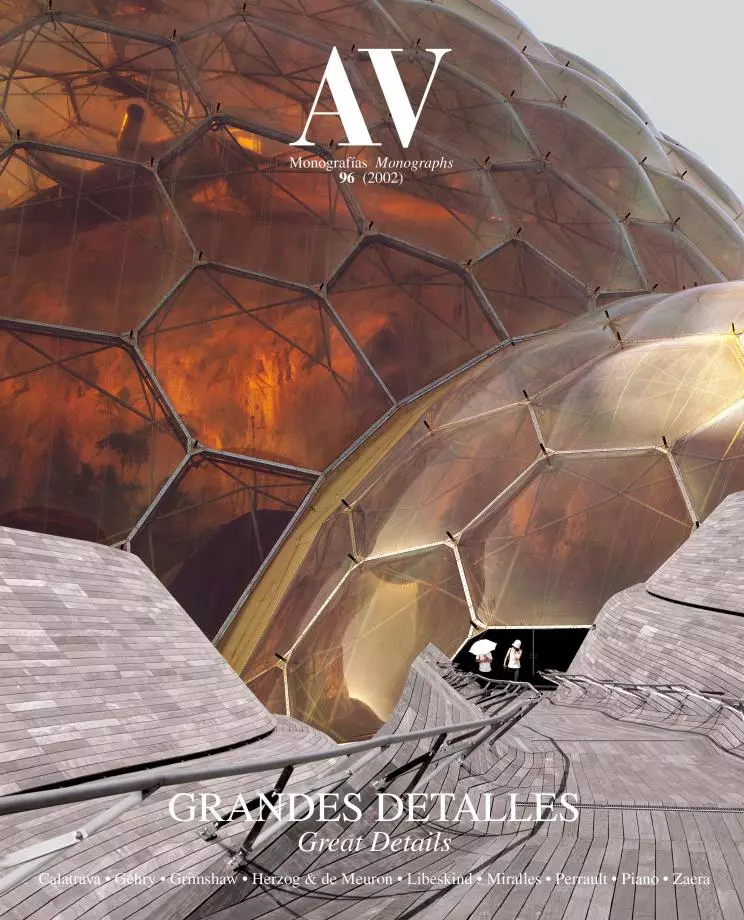

Imperial War Museum, Manchester

Daniel Libeskind- Type Museum Culture / Leisure

- Material Steel Metal

- Date 1997 - 2001

- City Manchester

- Country United Kingdom

- Photograph Hélène Binet Peter Cook

Deyan Sudjic

Manchester is a big, confident city, but an oddly shapeless one. It was the city in which Engels documented the living conditions of the world’s first industrial proletariat, the British working class, forged in Manchester’s explosive transformation from a small town into an industrial metropolis in the course of one single generation. But it ended up suffering the decline shared by many such cities in the wake of the collapse of manufacturing in Western Europe. And now, as if the whole city were set to default mode, that shapelessness is being faithfully reproduced in its struggles to fill the void left by its vanishing industrial past. Its big urban renewal projects are taking the form of isolated pieces of more or less distinguished architecture that appear lost in a sea of junk.

Salford Quays is a case in point. Manchester’s inland harbor, the terminal for the canal that linked city and sea in order to ship its production to the world, has gone from empty nothingness to busy nothingness in less than five years. It has acquired a tram link, a form of urban transport that Britain is still excitedly rediscovering; it has Michael Wilford’s colorful Lowry concert hall; and now it has Daniel Libeskind’s ImperialWar Museum North, an offshoot of a London Institution.

These are real achievements, yet they have brought with them some unexpected negative consequences: they have raised land values just enough to encourage private commercial development, but not enough for it to be development of any quality. Around these solitary cultural landmarks laps an aimless tide of car parking lots, designer shopping villages, business parks and themed restaurants which are so unsubstantial and so inconsistent that they could all blow away just as quickly as they have been so lovelessly dumped here.

Survival of an Idea

In sharp contrast, the Imperial War Museum is a real work of architecture, nourished by the quality of the ideas that have gone into it and also by the skills of the people who have built it. Startingly, in view of the enormous reputation that Daniel Libeskind has earned as the architect of the Jewish Museum in Berlin, the Imperial War Museum is only the third building of his career that he has completed. While it does not have the emotional punch of Berlin or its delicacy in the use of materials, it does demonstrate that the Jewish Museum was more than an isolated flash of brilliance.

The Manchester museum is the product of the conjunction of the London institution’s wish to establish a presence outside the capital and the desire of the local authorities to intitiate culture-led urban renewal. The Imperial War Museum conducted a beauty contest to find a suitable site. The Manchester location offered the greatest potential – and also a financial commitment. The next step was the international architectural competition won by Daniel Libeskind, who brought the project a high profile as well as a design with a sense of narrative that clearly appealed strongly to his clients. The museum was always going to have a tight budget, affording little more than an industrial shed. Libeskind’s designtookthat utilitarian shed and transformed it into a building charged with meaning. He addressed the potentially troubling issue creating a museum devoted to warfare, knowing full well that it could be perceived as trivializing to make entertainment out of full-on horror. It would be a dignified building, conceived as a globe shattered by the violence of war, from which a few shards have been salvaged and put back together in some chaoticform of more orless order. It convinced the museum immediately, and its poweras a conception has been able to survive both a one-third cut in the budget and the translation of the building from concrete to steel.

The museum is positioned on the edge of the canal basin that is the area’s only landmark. It is linked by an unnecessarily energetic new pedestrian bridge, one of the inevitable clichés of recent urban renewal, which connects it with Wilford’s Lowry Centre on the opposite bank. Libeskind doesn’t reveal all of its secrets at once. A curious collection of architectural fragments, it is set a little back from the water. Curved silver shapes float over murky grey wall whose dowdiness betrays the impact of a slashed budget. The entrance is a concrete tunnel that pierces the largest of the shapes, a curved tower that rises over the rest of the complex. Once across the threshold, you find that the imposing, apparently solid form is actually hollow. In fact, it is not even, strictly speaking, an interior space. Its walls are open to the wind. It provides a jolting pause, an unsettling reminder that this is a place where we are being invited to consider some of the more troubling issues that confront humankind. Crossing another threshold, you enter what feels like a subterranean lobby, full of the shops and cafés that are an inescapable part of the museum-going experience. On the wall you find a set of drawings of dissected globes, the Rosetta stone that Libeskind has provided to decode his architecture.

Libeskind takes his metaphors seriously. The black asphalt floor of the main exhibition is gently curved to reflect the section of the globe from which it comes, complete with a point marking the North Pole. Libeskind divides the museum into four shards – air, sea, land and water – reflecting the four theaters of warfare. It is organized around a spiralling circulation route, moving visitors up from that dark entrance space to two main exhibition areas, one for the permanent collection and the other for a programme of temporary exhibitions and then on to a restaurant looking out over the canal beyond.

This is the kind of museum that mixes objects (pride of place goes to a U.S. Marine Corps Harrier jump jet and a Soviet T=34 tank) with the paraphernalia of multi-screen projection. You can see the gun used to fire the first British shot in World War II, uniforms, propaganda and equipment. But there are also moving audiovisual displays that turn the interior of the museum into an Eames-like cinema. There is also a touch of phobia regarding the explanatory texts displayed by many contemporary museums. Captions are ultra-condensed in the condescending belief that this is all that we are capable of taking in. World War II, for example, is boiled down to a haiku 47 words long.

Thankfully, not all of the museum is organized in this frantic way. You can find yourself in front of a case full of the papers that regulated the lives of soldiers in World War II. A notebook filled with the names of next of kin of the crew of a destroyer. A fading telegram from the Admiralty commanding a young second lieutenant to be ready to leave the United Kingdom at 48 hours notice, “tropical uniform not required”. And you are left to ponder what it must have felt like to receive this invitation into the cold unknown on a breakfast table 62 years ago: it is the actual paper that sent a young man to war.

It leaves us to make our own conclusions rather than insisting on interpreting for us. Libeskind’s architecture provides an impressive, sober, yet unforbidding context for this intelligent strategy...[+]

Cliente Client

Imperial War Museum

Arquitectos Architects

Daniel Libeskind

Colaboradores Collaborators

Leach Rhodes Walker (arquitecto asociado associate architect); M. Aerni, W. James, M. Ostermann, S. Bisgard, S. Blanch, G. Brun, C. Duisberg, L. Fischer, L. Gräbner, J. Kuo, S. Milne, D. Richmond, A. Trumpf; Ove Arup (obra civil civil engineering); Gardnier & Theobald (gestión management); Mott MacDonald (instalaciones mechanical engineering); Event & Real Studios (diseño de la exposición exhibition design)

Fotos Photos

Hélène Binet, Peter Cook/View