Babyn Yar Synagogue, Kyiv

Life and darkness- Architect Manuel Herz

- Type Religious / Memorial Synagogue

- Material Wood

- Date 2021

- City Kiev

- Country Ukraine

- Photograph Iwan Baan

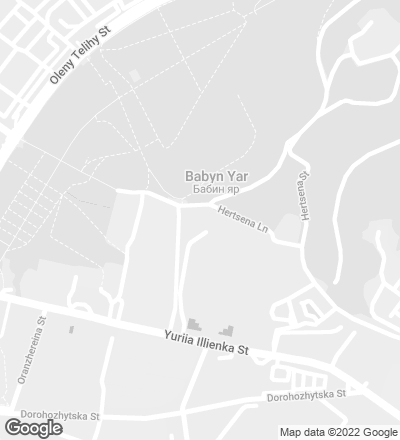

Babyn Yar is a wooded area with a deep ravine located in the west of Kyiv, Ukraine, that used to mark the edge of the city. It is the site of one of the worst massacres of the 20th century, when on 29 and 30 September 1941, approximately 35,000 Jews were shot and killed by German SS officers, their Einsatzgruppen, and other soldiers of the Wehrmacht, supported by local Ukrainian troops. Over the following weeks and months tens of thousands of additional Jews, Soviet prisoners of war, communists, Ukrainian nationalists, Roma, and patients of a nearby psychiatric hospital were murdered within the grounds of Babyn Yar. A ‘holocaust by bullets,’ it was one of the worst atrocities of our modern era.

The territory of Babyn Yar is marked by gorges and a strong topography. It was precisely this topography that the SS officers utilized, killing these tens of thousands of people without having to excavate mass graves. Through the mass killing, a new topography was created: a physical topography of death and murder. The very soil of Babyn Yar can therefore be considered sacred.

To build on land that has seen more murder and devastation than most other places puts the architect under immense responsibility. How do we respect the dead? Can we develop a response that is appropriate to the gravity of the site’s history? These questions were going through my head when I received the commission to design a synagogue on the grounds of Babyn Yar in October 2020. Of course the echoes of Yevgeni Yevtushenko’s majestic poem written in 1961 – “There are no monuments over Babi Yar” – accentuated my hesitation. Can we, or should we, build there at all? Isn’t the poem, and its extraordinary intonation by Shostakovich, the most profound commemoration we can imagine? While this is true to a certain extent, I also believe that architecture can bring a quality of commemoration to Babyn Yar that is truly different from other artistic disciplines, such as literature and music.

One might think that the appropriate response to this unbelievably inhumane massacre should be an architecture that is somber, minimalist, and monumental. The architectural history of Holocaust memorials is full of these. But I wanted to approach the project in a very different way. We will never match the monumental suffering of the massacre through a monumental architecture. Instead, I wanted to create a project that has a transformative dimension and establishes a new ritual on the site. In view of the site, which is literally and metaphorically drenched with blood, we cannot respond to the massacre bydesigning a building that imposes itself onto the ground and onto the narrative of history. The categorical and definitive message that a monumental and static building would suggest stands at odds with the tens of thousands of distinctive voices that perished in Babyn Yar. I was looking for a building that is polyvalent rather than demanding a conclusive reading. Hence, the idea was born to design an architecture that creates a new collective ritual, that has a performative and transformative quality, that is commemorative, just as it also creates a feeling of wonder and awe.

With the Jewish people often being referred to as the ‘People of the Book,’ the idea of referencing a book in the design is maybe not all that surprising. I was then thinking of the pop-up books that are so fascinating. From a flat, almost two-dimensional object, they unfold into three-dimensional volumes, often into scenographies with an architectural character. I believe no one can resist the temptation to open these books and see how a new and surprising world unfolds. In a certain way, this is exactly what happens when we come together to pray in a synagogue: we open a book together (either the Siddur, i.e., the Jewish prayer book, or the Bible). Reading this book in the collective of the congregation also opens a new world to us. A world of stories, of histories, of morals, of love, and of wisdom.

For the interiors of the Babyn Yar Synagogue, I wanted to reference the historic wooden synagogues of western Ukraine, dating back to the 16th century but all destroyed in the Nazi era. Their use of ornament and writing on the walls is fascinat ing. There was in particular one historic photograph of the Gwozdziec Synagogue that I had been studying which was strikingly beautiful, featuring also a text on the walls. Surprisingly, it is quite an obscure blessing involving the interpretation of dreams, to transform nightmares into good dreams. I immediately thought that there can be no better leitmotiv for the Babyn Yar Synagogue than this blessing that turns nightmares into good dreams. This blessing now occupies the main wall of the Babyn Yar Synagogue.

I started working on the Babyn Yar Synagogue just two weeks after my wonderful wife, Xenia, gave birth to our son, Max. Hence I was engaged in a topic of murder and unbearable suffering, and at the same time marveling at this new, tender human being. When I looked into the beautiful face of our little son, I saw his great curiosity and his immense joy of experiencing life. My son taught me that the Babyn Yar Synagogue cannot only be about commemorating the past, but must also be about opening up a new future. It needs to be a project that turns a nightmare into a good dream. A project that is not entrenched in death and destruction, but celebrates the beauty of life.

The Cruel Noise of War

As I write this, Babyn Yar is being attacked. The site of one of the worst massacres of the 20th century, where in 1941 tens of thousands of people were killed within a few days at the hands of the Nazis, has again become a site of war and killing. Five people died when a TV tower and a sports center located on the grounds of Babyn Yar, on the outskirts of Kyiv, were hit. Beyond the incredibly tragic loss of life, it represents a destruction of history, and a violation of all the over 33,000 victims who died there eighty years ago. Within a horrendous war, the looming destruction of a memorial site of this scale and meaning is another horrific chapter debasing our humanity.

When in October 2020 I was commissioned to design a synagogue for the site of Babyn Yar, I was extremely moved by the honor to build on this territory that represents one of the ‘Ground Zeros’ of European (or even World) history, and by the responsibility that this imposed on me as an architect. Of course one aim was to shape a building that commemorates the past. Even more, with its fragile wooden construction, transformative quality, and colorful painting, making it different from any other kind of ‘monumental’ and commemorative architecture known to me, I wanted to design a building in which Jews could pray, but also one that would be open to visitors and citizens of Kyiv. It was to be a place in which together they could celebrate the beauty of life. As the building was to open with the commemoration of eighty years since the massacre on 29 and 30 September 2021, the period of design and construction, taking a mere six months, was as intense as the practice of architecture can get. During this time, I got to know an astounding and deeply committed group of people in Kyiv who have since become close friends. Within only seven days of Russian invasion into Ukraine, they have been drawn into a bitter war, and many of them have become refugees.

On 1 March 2022, rockets struck just 150 meters from the synagogue. Only a few months after its inauguration, the synagogue is caught up in war, which only celebrates death. What is the point of commemorating history if the lessons to be learned are forgotten and ignored so easily? It leaves me speechless, numb, and powerless. Compared to other commemorative architecture that is mostly built of stone and concrete, the fragility of the wooden synagogue means that it must be cared for every day. This daily care, and its fragility, is precisely what represents actual commemoration. The synagogue needs its community, its audience, and its visitors. With the site now a war zone, it has been robbed of this community. I pray for the people of Kyiv and of Ukraine, that the savagery of the war end as soon as possible, and I hope that the synagogue can eventually regain its community, so that the lessons of fragility are not drowned out by the cruel noise of war...[+]

Obra Work

Sinagoga en Babi Yar

Babyn Yar Synagogue, Kyiv (Ukraine)

Cliente Client

Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Foundation.

Arquitectos Architects

Manuel Herz Architects / Manuel Herz (socio partner); Maxim Gabai, Ben Olschner, Isabella Pagliuca, Angeliki Giannisi (equipo team).

Consultores Consultants

Oleksandr Laptev (dirección de obra site supervision); Dmytro Pisarevaliy, Yaroslav Novitskiy (ingeniería engineering); Oleksiy Makukhin (gestión de proyecto project management); C.I.Form (pintura del techo ceiling painting); Galina Andruschenko (pinturas murales wall paintings).

Contratista Contractor

Budsok.

Superficie Area

150 m².

Fotos Photos

Iwan Baan.