Tadao Ando’s perfection is painful. His concrete constructions, austere and naked like luminous cells, attain such geometric and material precision as to hurt the senses with the cold cutting edge of their inhumane exactitude, and the excessive and essential discipline of his rough walls continues to sting one’s gaze. Former boxer and self-taught architect, educated through his travels and the observation of craftsmen, this Japanese born in Osaka in 1941, and who has already received every imaginable prize, is today a mythical figure in the international scene, where with religious fervor he has been propagating his demanding conception of architecture for over fifty years now. From the start, Ando’s career has been marked by an obstinate and penitent purity which has made him master and priest of a large congregation of people faithful to elemental geometry, sculptural concrete, and scenographic light.

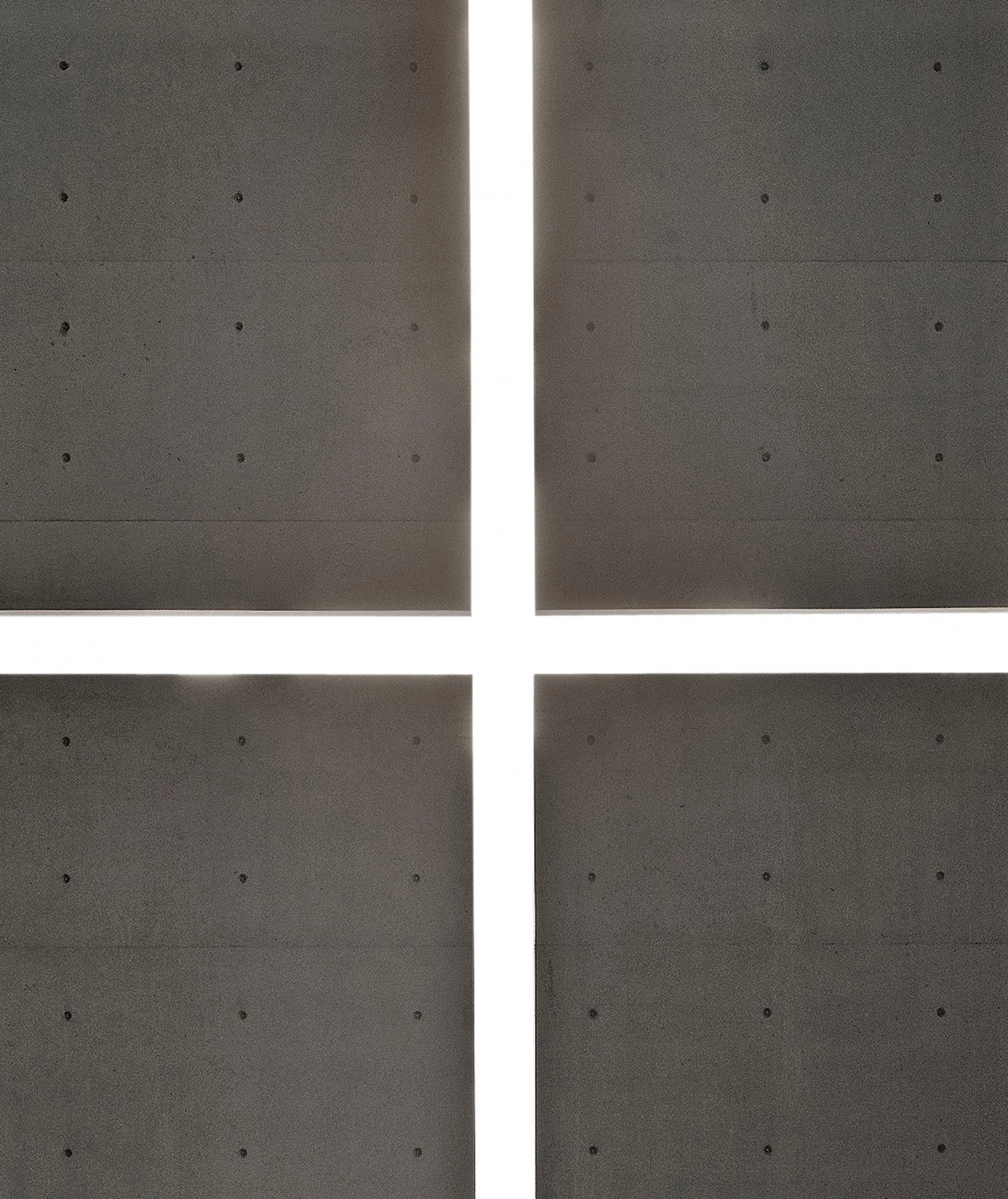

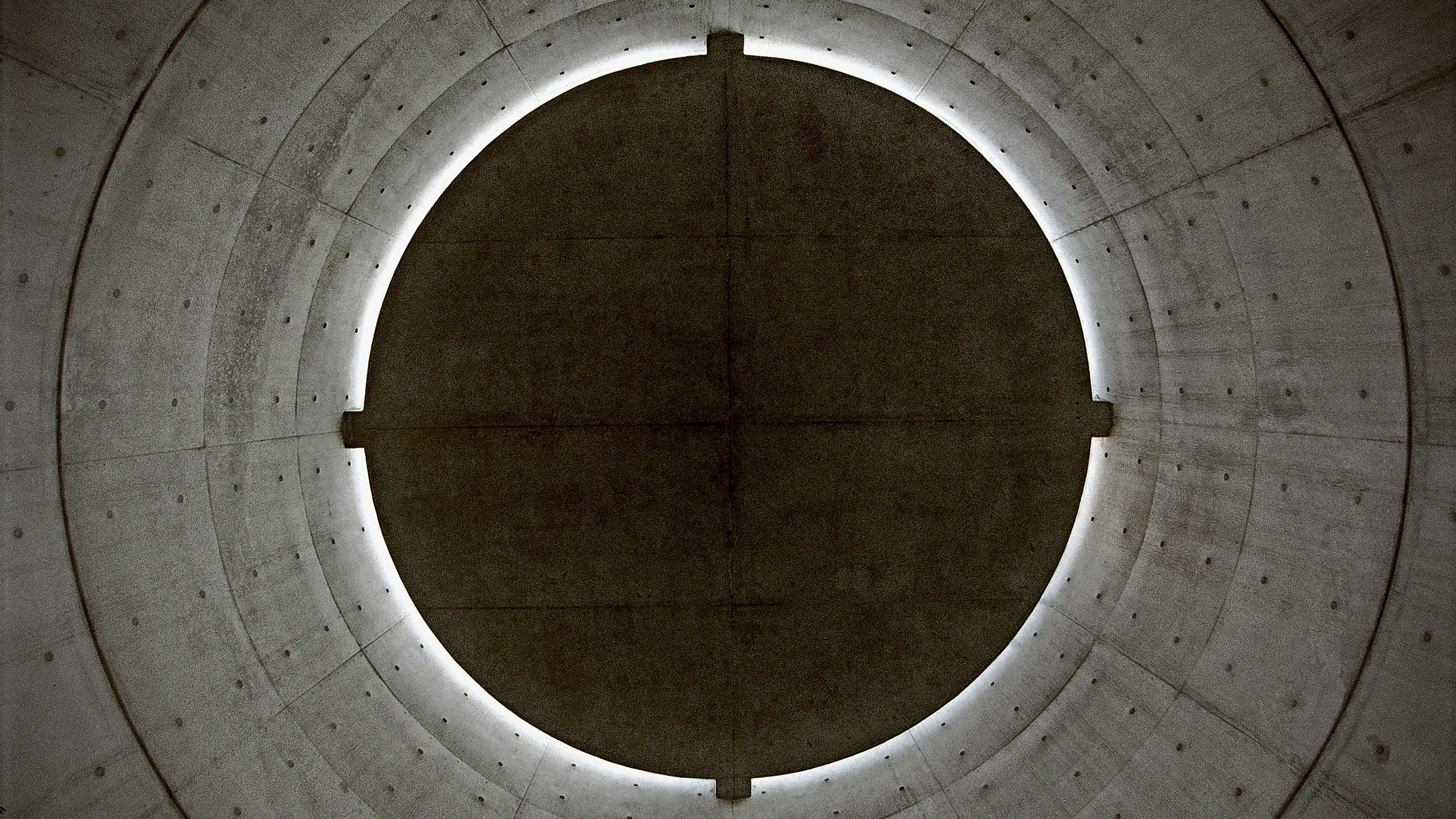

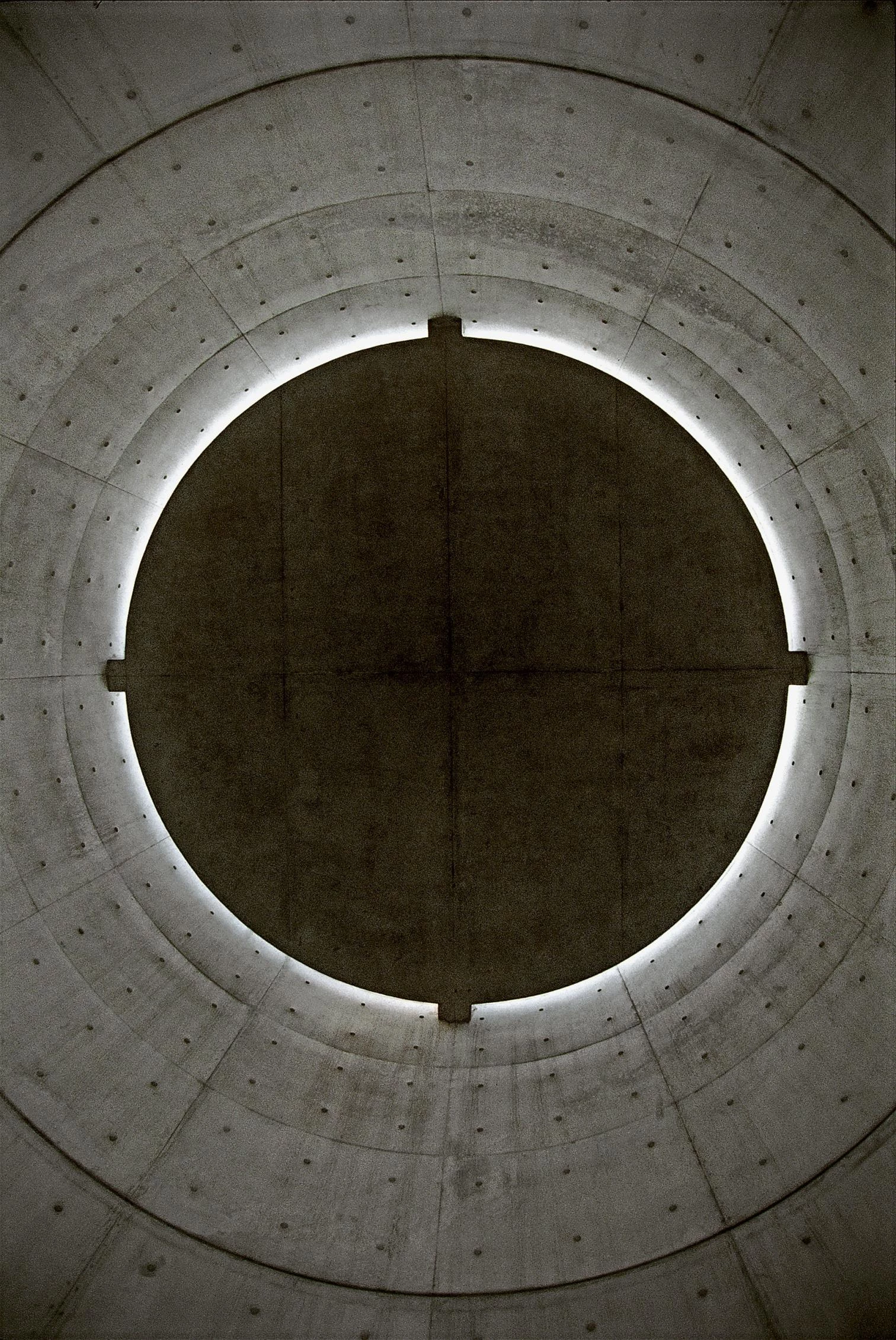

The compositional rigor, the constructional thoroughness, and the rhythmic and ritual orchestration of his itineraries produce a monumental architecture, abstract, silent, and eternal; a closed architecture indifferent to its surroundings, ignorant of comfort or function; a sacred and sadistic architecture, austere and autistic, virginal and violent. Exquisite concrete boxes with no other ornament than the geometric mark of plank molding sheets, with narrow slots for light to shine through, grazing the floor, or for people to enter and exit through, performing ceremonies and pretending to inhabit those nude and empty spaces. Huge sheets of glass, silent pools, glass block cylinders and forests of pillars, processional ramps, simple forms that intersect to generate musical complexities: whether offices or dwellings, commercial buildings or museums, his severe precincts are all temples of a minimalist cult to interior perfection.

Tadao Ando has come a long way from the dry radicality of the Azuma House or the brutal delicacy of the Koshino House to the articulated elegance of his religious buildings or the symphonic solemnity of his museums. A long but straight road: his three Christian churches of the second half of the 1980s – the Chapel of Mount Rokko, the Church on the Water, and the Church of Light – differ from the concrete houses of the 1970s only in the use of the cross as a symbolic element; his three major museums of the 1990s – the Children’s Museum, the Museum of Literature, and the Museum of the Forest of Tombs – use the same compositional instruments employed in his residential architecture and manifest identical material preferences, though transferred to places of greater interest in terms of landscape and program. Only his ephemeral buildings, from the Kara-za Theater to the pavilion in the Seville Expo, or his large-scale projects, all in love with the ovoid shape, follow different geometric and constructive logics.

The evident modern nature of Tadao Ando’s work – his debt to the purist geometries of his revered Le Corbusier, whose projects he insistently reproduced until becoming “imbued with his spirit” is as obvious as his debt to the monumental forms of Louis Kahn – has paradoxically impelled his critics to seek Japanese roots for his architecture, with the inevitable help of the author himself, who does not hesitate to suggest ethnic interpretations for unmistakably cosmopolitan buildings. Kenneth Frampton, who introduces his work in this monograph, elected him early on as an example of ‘critical regionalism’ – on a par with Mario Botta, another fervent follower of Le Corbusier and Kahn, and with whose elemental geometries Ando has more than one thing in common – and subsequent exegetes have sprinkled their texts with references to cultural syncretism, Shintoist rites, and the tea ceremony: any worthy critique on Ando is nowadays expected to mention the terms kabuki, haiku, and ikebana, and to present the architect as a perfect hybrid of Donald Judd and Zen master.

More convincing than the placid search for traditional foundations is the reading of Ando’s architecture in the split context of post-Hiroshima Japanese culture, profoundly westernized and dramatically uprooted and torn. The filmmaker Akira Kurosawa and the writer Yukio Mishima have been mentioned in line with Ando, but the epic dimension of their works is not present in the intimate and monastic constructions of the autodidact from Osaka; the painful beauty, contained violence, and disturbing nakedness of his essential architecture have more to do with Nagisa Oshima and Kenzaburo Oé, whose cinematographic and literary narratives take place in mythical spaces, the irreversible disappearances of which ignite self-absorbed nostalgia and silent ire. Ando’s buildings are sacred fables, which however no longer evoke a vanished transcendence but the perturbed pain of its absence. It is perhaps this introverted insurrection against the loss of meaning that helps one understand Ando’s frugal and severe stoicism as a quest for spiritual perfection, in a world that shuns the sacred.