The Construction of Continuity

Twenty-five years later, David Chipperfield stays put. The London boutiques are now buildings in four continents, but the architect sticks to his initial traits: sensual handling of materials, lively orchestration of uses and laconic elegance of language. In contrast with the experimentalism of the Architectural Association where he studied, and also with the technical leanings of the offices of Rogers and Foster where he worked, this uncommon Englishman found his third way in the rigorous and lyrical axis that joins Milan with Berlin via Zurich. After the Japanese episode, in which he used concrete prisms to explore the synthesis of Le Corbusier and Kahn canonized by Ando, Chipperfield seeked his tectonic, sober architecture in the Swiss and German extensions of the Tendenza, which turned the poetic dogmatism of the Italians into a contextual pragmatism devout of continuity.

Though during his already long career he has not ceased to experiment with learnt languages – from the nod to Siza in Corrubedo to the Aaltian gesture of the Ansaldo project or the expressionist plan of the Iowa library –, the core of this work is the Rossian revision of modernity, interpreted with the ascetic forms of the ETH?disciples of the Milan architect. The first work that earned broad recognition was the River Museum, stilted warehouses seen as neovernacular but surely indebted to Rossi’s fascination with anonymous sheds, and the same can be said about another British project of ten years later, the Gormley studio. For its part, the commission that marks a turning point in his career, Berlin’s Museum Island, uses a rigorist vocabulary that joins Döllgast and Grassi, and that abstract classicism extends to other German works, like the much praised Museum of Literature in Marbach.

Berlin marks the international launch of Chipperfield, and the last decade has witnessed an exponential growth of his office, with projects in Germany, Spain, Italy, United States, China and even Sudan. This productive reprise, which inevitably blurs the profile of the firm, still holds on to the thread that weaves empiricism and emotion within a postmodern discipline. Rossi used to name Mies, Loos and Tessenow as guiding masters, and probably Chipperfield feels at ease under the watch of the three:?Tessenow for the essential wisdom of tradition; Loos for the mix of critical austerity, tactile comfort and scenographic raumplan; and Mies for almost everything else, from the neoplasticist beginnings evoked in the sculptural ‘architectons’ or the mimetic tribute to the brick houses to the reinterpretation of the glass skyscraper or the exact horizontal articulation of the Coesfeld offices.

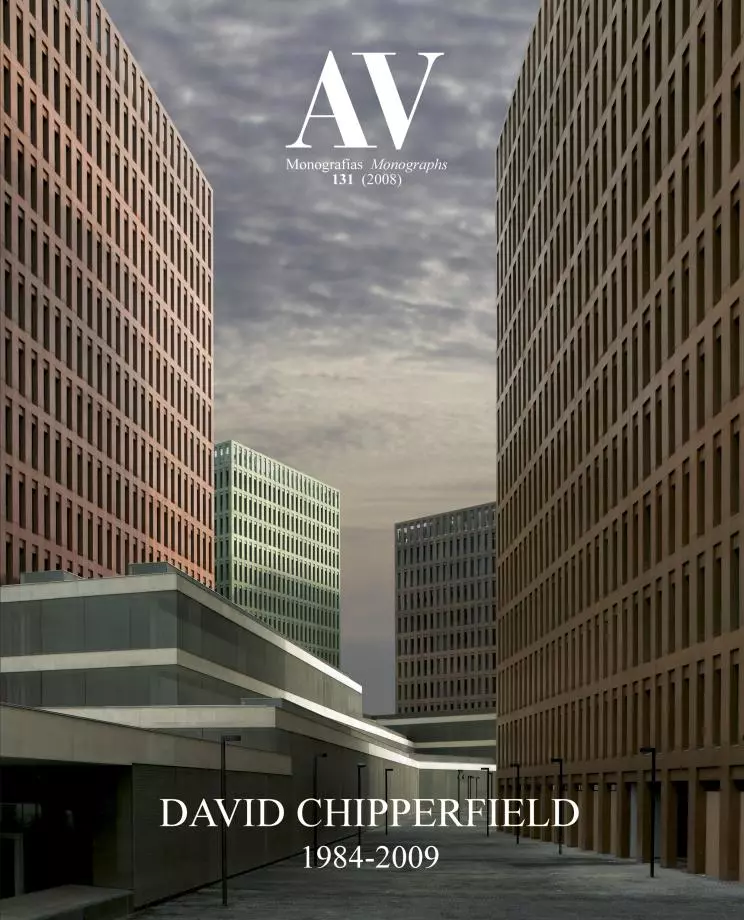

In this expansive period, the new urban developments – from the courtyards of the Venetian cemetery to the prisms for justice campuses in Salerno and Barcelona – keep the metaphysical taste of the Tendenza, though with chromatism closer to Morandi than De Chirico, whereas a gusto for musical randomness shakes the plans of Hepworth Gallery or Ninetree Village, using disorder or fragmentation as antimonumental devices rather than as references to the world’s convulsions. This mannerist sensibility, which is not incompatible with the dazzling ease of projects like those of Teruel or Valencia, colors in the work of the mature architect with a skeptic melancholy, perhaps because his desire to bring order into the confusion of cities and lives is marked with the stamp of useless passions. But it is precisely in this project of redemption through matter and memory that his humble and resistant grandeur resides.

Luis Fernández-Galiano