Valencia Gravity and Grace

The launch of the America’s Cup, which opened its icon building, a tragic subway accident and the Pope’s visit coincided this month in the booming Mediterranean city.

Valencia lived a summer of ups and downs: from the winds on the sails to the victims in the trains, and from there to the visit from the Vatican. In a matter of days it moved from the euphoria of nautical triumphs to the sense of total defeat caused by the railway ordeal, to then seek volatile consolation in the pastoral voice of a philosophical pope. In the first weekend of July, twelve boats from five continents took part in the world’s oldest competition, for which Valencia had won the bid to be a venue against nearly a hundred other candidate cities. The final regatta prior to the America’s Cup of 2007 served as occasion for the opening of the Foredeck, a lookout building designed and built in just eleven months by David Chipperfield and b720/Fermín Vázquez as center and symbol of the event. The following Monday, the underground station Jesús was the scene of the worst accident ever to happen in a Spanish metropolitan railway. Its over forty deaths switched the city’s mood into one of mourning, and not even the mass fervor of the pope’s visit the following weekend managed to dissipate the grief of so many desolate families.

The City of the Arts and Sciences by Calatrava was the backdrop of the Pope’s visit, while the new building by Chipperfield in the port was the stage for the inauguration parties of the America’s Cup preparatory races.

From 1934 to her death in 1943, the French mystic writer Simone Weil wrote a diary that was published posthumously, in fragments, under the title Gravity and Grace: two words that expressed the opposition of the heaviness of the world and the lightness of the spirit, but which also perfectly sum up the contrast between the solemnity of death that strikes as collective tragedy and the frivolity of the media event, be it sport-related or religious, that congregates masses around a spectacle or a message. Valencia shifted its attention from the immaterial hustle and bustle of breezes and boats viewed from a lookout, to the somber drama of human catastrophe in an underground labyrinth, closing the circle with the ephemeral architectures and winged words of a pious crowd that chose the aerial forms of Santiago Calatrava for backdrop. Gravity and grace are terms that express the changing mood of the city as much as they suit the contradictory nature of the America’s Cup building whose launcing party started this week of passions.

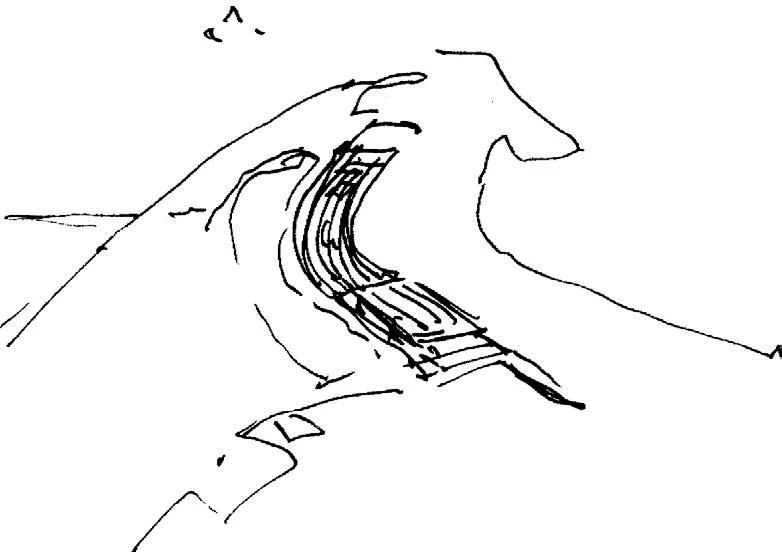

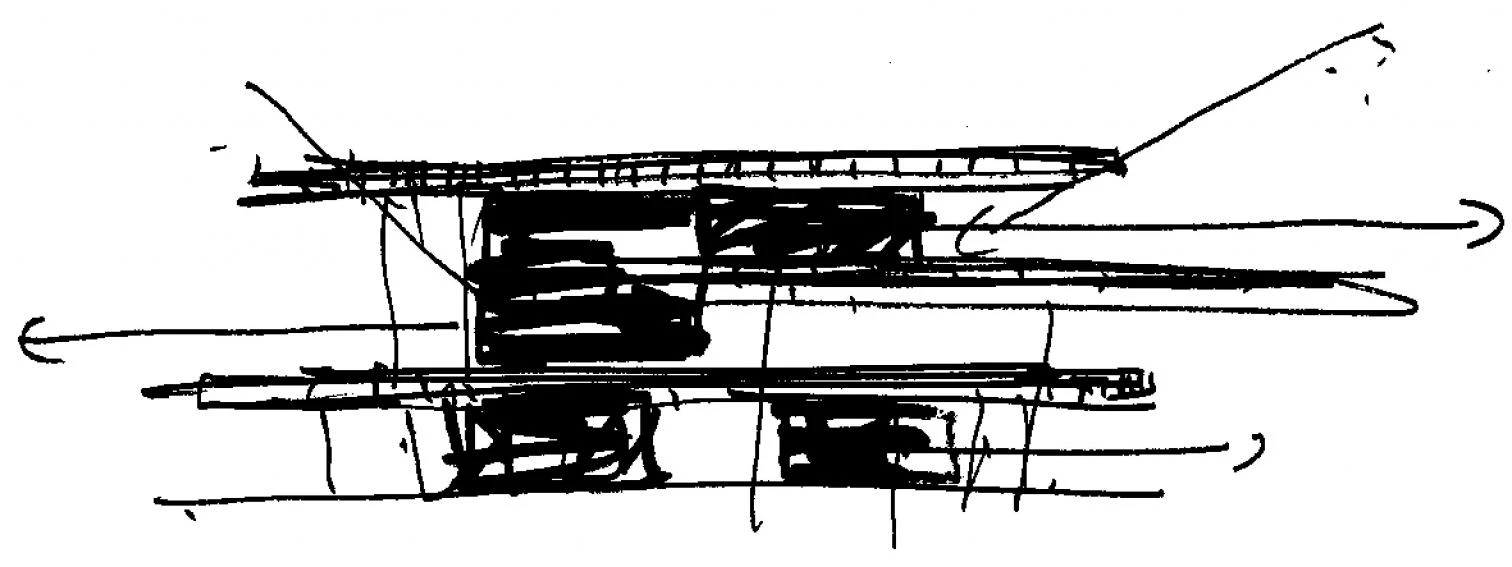

The Foredeck Building of the America’s Cup, also called Veles e Vents, is formed by cantilevered platforms that frame the views and protect visitors and spectators from the sun, rising in the dock like an abstract landmark.

To design and build the Foredeck, also called Veles e Vents as a tribute to a poem by Ausiàs March, Chipperfield and b720 won over competitors like Jean Nouvel, Von Gerkan & Marg, Carlos Ferrater, or Alejandro Zaera. The building is formed by four large platforms that rise with sculptural confidence at the end of the dock, extended along the new canal with a parking lot for 800 vehicles and a garden walk that links this landmark to the seafront and the Malvarrosa beach. “The beach of Sorolla and Blasco Ibáñez,” says Mayor Rita Barberá as we lunch in Las Arenas, a big new hotel built in clas sicist style that is a counterpoint of opulence to the pure geometries of the Foredeck. Here, the gravitas of Chipperfield’s work dissolves in the Mediterranean light of the huge cantilevers, clad in a white-enameled steel that makes them look weightless –an impression reinforced by the transparency of the building’s main volume and the almost imperceptible glass parapet of its perimeter.

The spacious shaded terraces – the two lower levels for public use, the two upper ones reserved for guests of the organization – are of course the essence of the project. It is there that the main activities of the building happen: receiving visitors and watching regattas by day, parties of sponsors and gatherings of crews by night. Each of the twelve teams participating in the event has its own base in the port – provisional structures several floors high containing workshops, gyms, dining rooms, offices, shops, and reception areas for guests and the press, outstanding among which is the one Renzo Piano built for Luna Rossa, the Italian ship sponsored by the firm Prada, with its intelligent cladding of recycled sails and a large boutique on the top floor that one gets to by escalator. But only the Foredeck brings everyone together on neutral ground, and it does so with an ease and elegance that makes it hard to imagine any other project on the spot. The dead-lines for design and execution were so tight (due to the delays caused by the change of government in Madrid and the attendant political contest for the control of the event) that the work has small im-perfections in the details and finishes that mortify Chipperfield. Responding to the congratulations of Public Works Minister Magdalena Álvarez –dressed in sailor outfit to watch the regatta from the sea – the British architect is more keen on stressing what is still lacking than on patting himself on the back for what has already been done.

This attitude is typical of an architect who is stub-born and demanding when it comes to the material quality of his buildings, and who is obsessively self-critical about his work in general. Nevertheless, Valencia’s Foredeck is proof, precisely, of the force of architectural ideas, the resilience of concept against haste or misunderstandings, because the initial proposal of the slabs in levitation, with terraces in shade and luminous edges that define an abstract geometric sculpture, so persuasively reconciles the functional needs of the lookout with the sculptural needs of the landmark that no small defect or error can damage the result. The building’s lightness is perhaps – as Weil would have had it – that of ideas in strife with matter, but it may also be that which suits a fleeting world, incompatible with the gravity of timeless certainties, a liquid circumstance that upsets Joseph Ratzinger as much as it did his fellow-German Karl Marx, who a century and a half ago described the experience of modernity in The Communist Manifesto: “all that is solid melts into air.” In this Valencian summer of gravity and grace, the weightless ‘sails and winds’ building reflects the enterprising mood and hopeful dynamism of the town better than the rhetoric colossalism of the City of the Arts and Sciences, the place where St. Peter’s successor delivered his message of consolation. The Fisherman’s next visit, by boat, and his next homily, from the sea.