“I’m a realist of the old school,’ Belbo whispered to me. “I understand only Mondrian. What does a nongeometric picture say?”

Umberto Eco, Foucault’s Pendulum

Mondrian would have liked to hear that from Jacopo Belbo. In Eco’s novel, the main characters attend the opening of an exhibition of a painter who has evolved from geometric abstraction to symbolism: “There were mountains that shot rays of light, which were broken up into a fine powder of pale spheres, and there were concentric skies with hints of angels with transparent wings…” None of that, according to Belbo, is realistic: Mondrian’s canvases are more real. No other statement would have pleased the painter more.

Without a doubt Belbo thinks, like the realist Courbet, that representations of the imaginary – whether angels or luminous mountains – are more deserving of the adjective ‘abstract’ than geometric art is. Piet Mondrian, he in effect tells us, is a realist painter. Quite similar to this view, albeit rather denser, is the theorization on nonfigurative art that the Dutch master makes in his 1937 esssay ‘Plastic Art and Pure Plastic Art.’

Running through the text, indeed, is the idea that nonfigurative art aims to portray objective reality, whereas figurative art confines itself to a subjective depiction of reality. “Subjective reality and relatively objective reality: this is the contrast. Pure abstract art aims at creating the latter, figurative art the former. It is astonishing, therefore, that one should reproach pure abstract art with not being ‘real’…”

This concern for reality leads Mondrian to dress his essay with numerous references to “fundamental laws hidden in reality,” the “fixed laws of the plastic arts,” “the great hidden laws of nature which are established in its own fashion,” “always true” and “immutable” laws that show clearly only in non-figurative art. In this way, pure art is like pure science in its search for basic laws of nature, and no less useful.

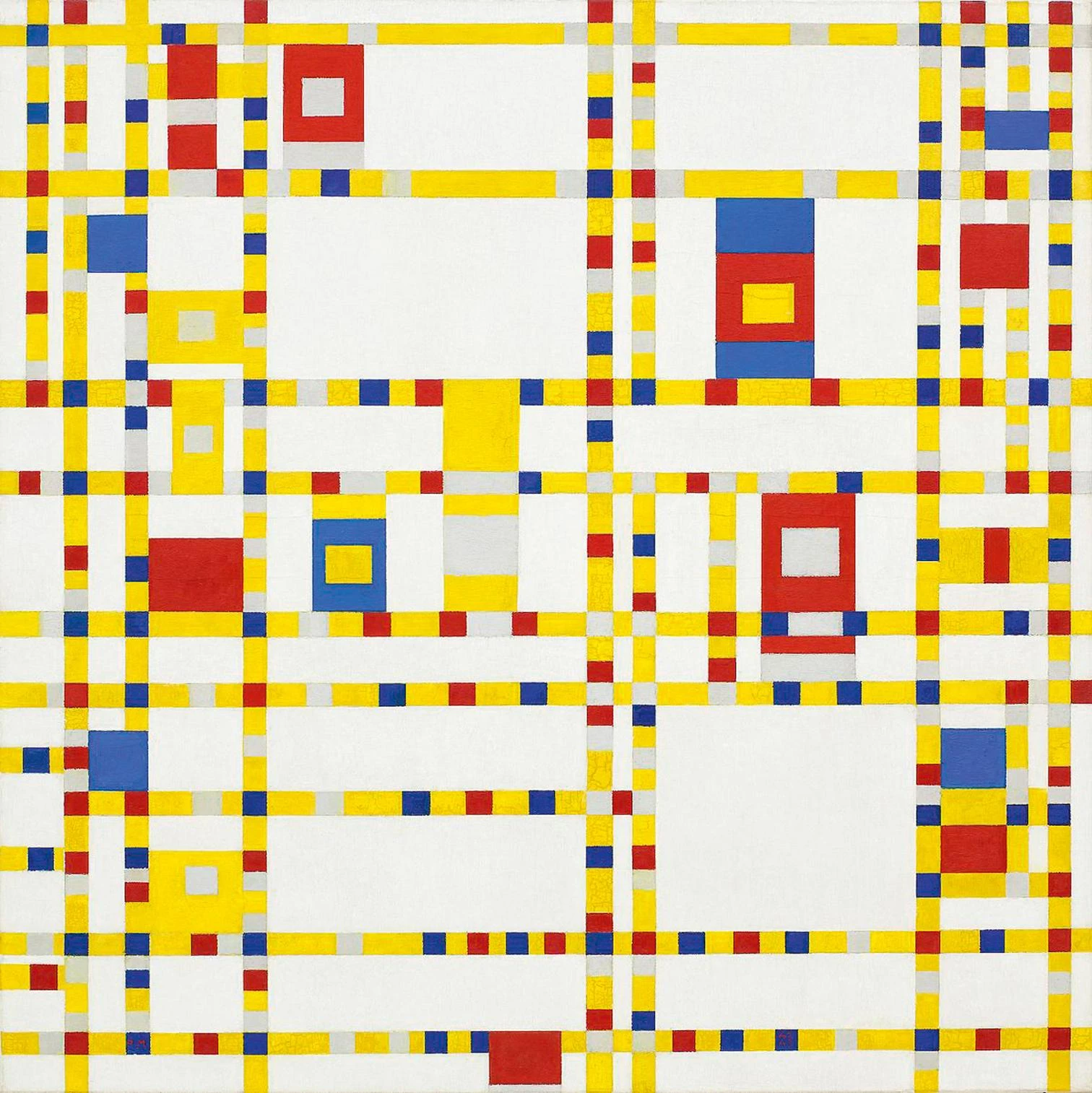

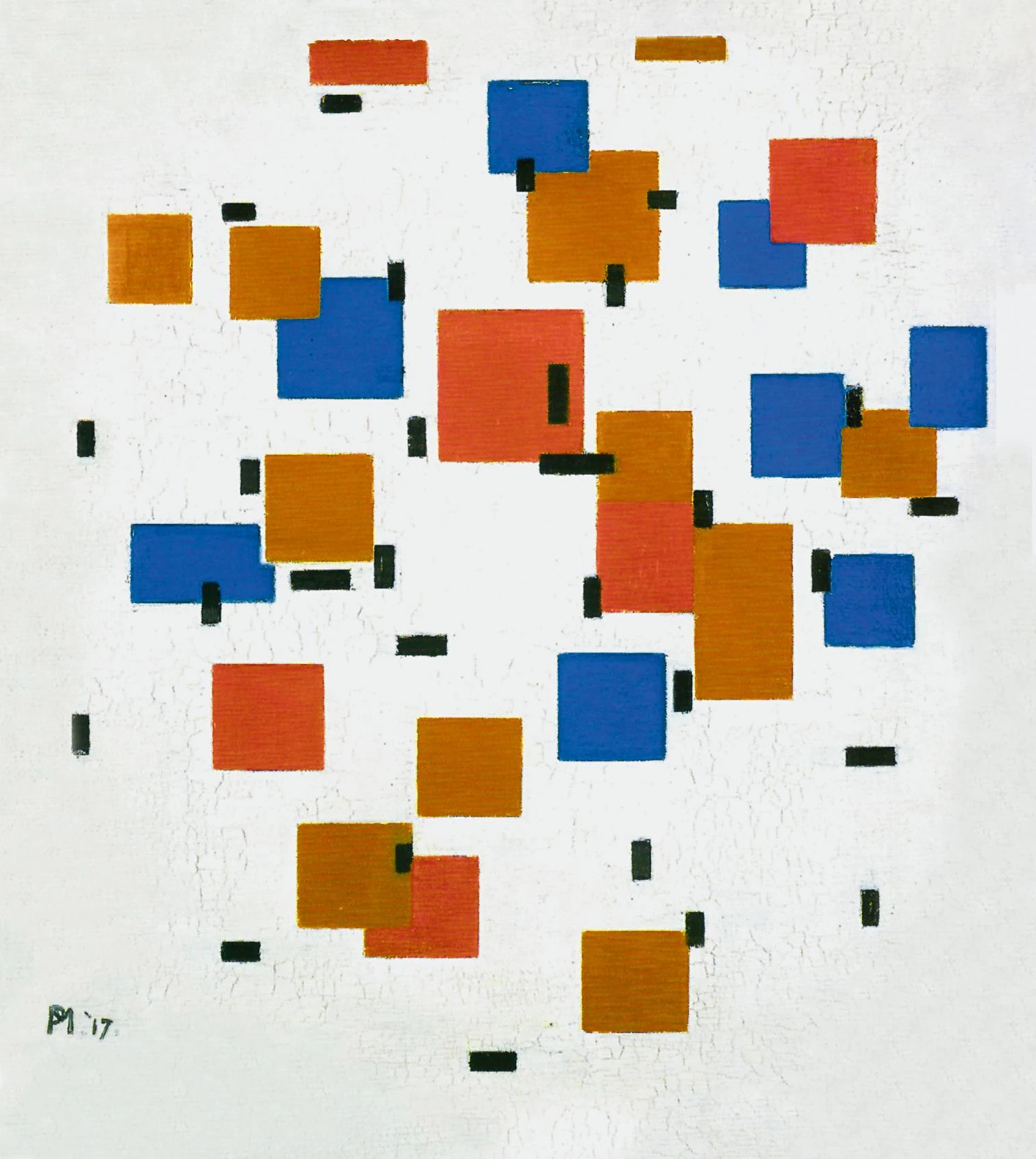

As for the laws themselves, the painter distinguishes between “the fundamental law of equivalence which creates dynamic equilibrium and reveals the true content of reality” and the secondary laws that govern the use of constructive elements. The result of these laws, after “the destruction of particular form” and “the construction of a rhythm of mutual relations,” and after many invocations to clarity, simplicity, and denaturalization of matter, is more or less expected: straight lines intersecting, rectangles, and primary colors. These are the “laws of pure plastic art” and the “essence of art.”

Reading this text (a long time after it was written) raises at least two questions: what it has of interest and relevance on its own, and how useful it is in studying the author’s painting work. At the risk of overstepping bounds, let me at this point warn the reader that my answer to both questions is rather negative, but I cannot resist the temptation to use the text to make some comments on the theorization of the plastic arts.

As a theoretical statement on nonfigurative art, Mondrian’s essay is in my opinion rather poor: at once schematic and obscure, the essay is built on repeated oppositions of the universal-individual, objective-subjective, intuition-thought, body-spirit, and content-form kind. His preoccupation with hidden laws of nature, more theosophical than positivist, is rather unconvincing when he puts it in the context of contemporary science; his assessment of elites as pioneers of human evolution and his criticism of intelligibility as a factor of degradation that has affected religion and art equally are annoyingly trivial; and the manner in which this confusing conceptual magma is channeled towards the three or four stylemes that characterize Mondrian’s paintings from the 1920s on is as forced as it is predictable.

After a sermon of very little substance and even less literary worth, the preacher-magician pulls the stylistic rabbit out of the theoretical hat and his tricks become obvious. Though it was Theo van Doesburg who first convinced Mondrian to turn his notebooks of scattered thoughts into publishable texts, one cannot help feeling weary of the inexhaustible enthusiasm of the driving force of De Stijl.

In truth, artists’ writings prove disappointing to anyone picking them up who is drawn to the brilliance of their works more than driven by historiographic curiosity. Some writings by artists – Kandinsky, Malevich – at least help us understand intentions. Others – by Mies, Klee – do not even do that. And almost all pale beside texts by contemporary critics. Take the Mondrian case. Read his 1937 essay after skimming, first, through Alfred Barr’s comments on non-figurative art in his 1936 book Cubism and Abstract Art, then Meyer Shapiro’s response in his article of the following year, ‘Nature of Abstract Art.’ It is hard to avoid the conclusion that critics understand abstract art better than painters do. I would only reproach both critics for taking the opinions of artists so seriously!

Without meaning to sound gratuitously provocative, the truth is that, since we are comparing his essay with other texts of the period, Mondrian’s reminds me of one by another revolutionary, also dated 1937 but belonging to a very different sphere: ‘On Contradiction,’ one of Mao Tse Tung’s best known philosophical essays. The Chinese leader’s reflections on the two conceptions of the world, the universality and particularity of contradiction, and the principal contradiction and principal aspect of contradiction, manifest the same dualistic simplism that Mondrian’s article does, as well as a very similar mix of the trivial and the obscure. It could be said that the radical transformations of society and art can be done with flimsy theoretical carpentry, perhaps because this frame of theories is not as much a resistant structure of revolutionary construction as it is an added scaffolding that can be dispensed with.

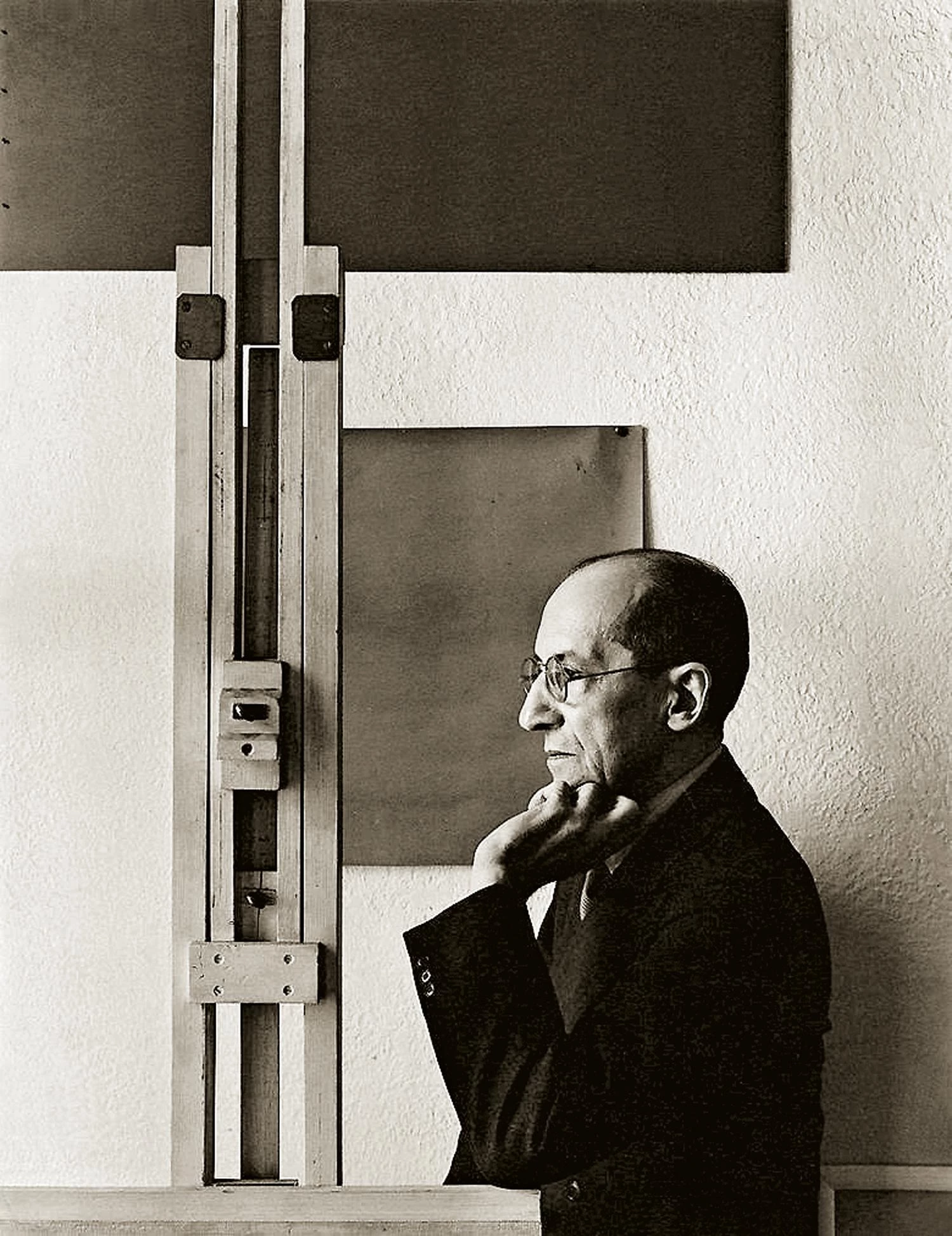

Nevertheless, even granting that Mondrian’s text may be of little interest on its own accord, we should keep in mind the hardly disdainable circumstance that the author of these pages is one of the century’s most dazzling artists: for whatever light it might throw on his painting work, the essay should be considered worthwhile. But on this point, too, I have reservations. As happens with so many texts by the painter, Mondrian’s stiff pen is no help in interpreting his exquisite retina.

Experts on Mondrian have placed much, though variable, importance on his writings. Hans Jaffé, Joop Joosten, Robert Welsh, and Meyer Shapiro himself give the painter a theoretical profile – more or less sharp, as the case may be, but never absent. Few are those who, like Kermit Swiler Champa, dare to opine that “his theoretical writings are defensive, often creatively dull, self-justifying, and coming long after the facts… at most, written theory is a kind of doctrinaire translation of that small part of the pictorial achievements that genuine artists capture verbally.” Although he is in a minority, I think Champa is right, and maybe Mondrian himself suspects something to that effect when, already an old man, he tells Charmion von Wiegand: “You must remember, Charmion, that the paintings come first and the theory comes from the paintings.”

The same recognition and upholding of intuition is found in what is perhaps the most illuminating paragraph of his 1937 text: “Intuition enlightens and so links up with pure thought. They together become an intelligence which is not simply of the brain, which does not calculate, but feels and thinks… those who do not understand this intelligence regard non-figurative art as a purely intellectual product.”

This may be the only line where we can discern the paradox that, because Mondrian’s painting is more a result of plastic intuitions than of theoretical reflections, his extreme refinement and his violent purity cannot be conceived without the philosophical temper and fundamentalist outlook that give rise to his writings. They come from the same mystical and metaphysical crucible as his oils do, but are a subordinate and parasitic phenomenon.

Interpretative lucidity and plastic genius seem to make bad bedmates. The writings of some of Mondrian’s De Stijl colleagues – J.J.P. Oud or Theo van Doesburg – are now read with more enthusiasm than the repetitive and cumbersome speculations of the iconoclastic, Calvinist, and dogmatic Dutch theosophist, but none of them can hope to compare with him in artistic caliber.

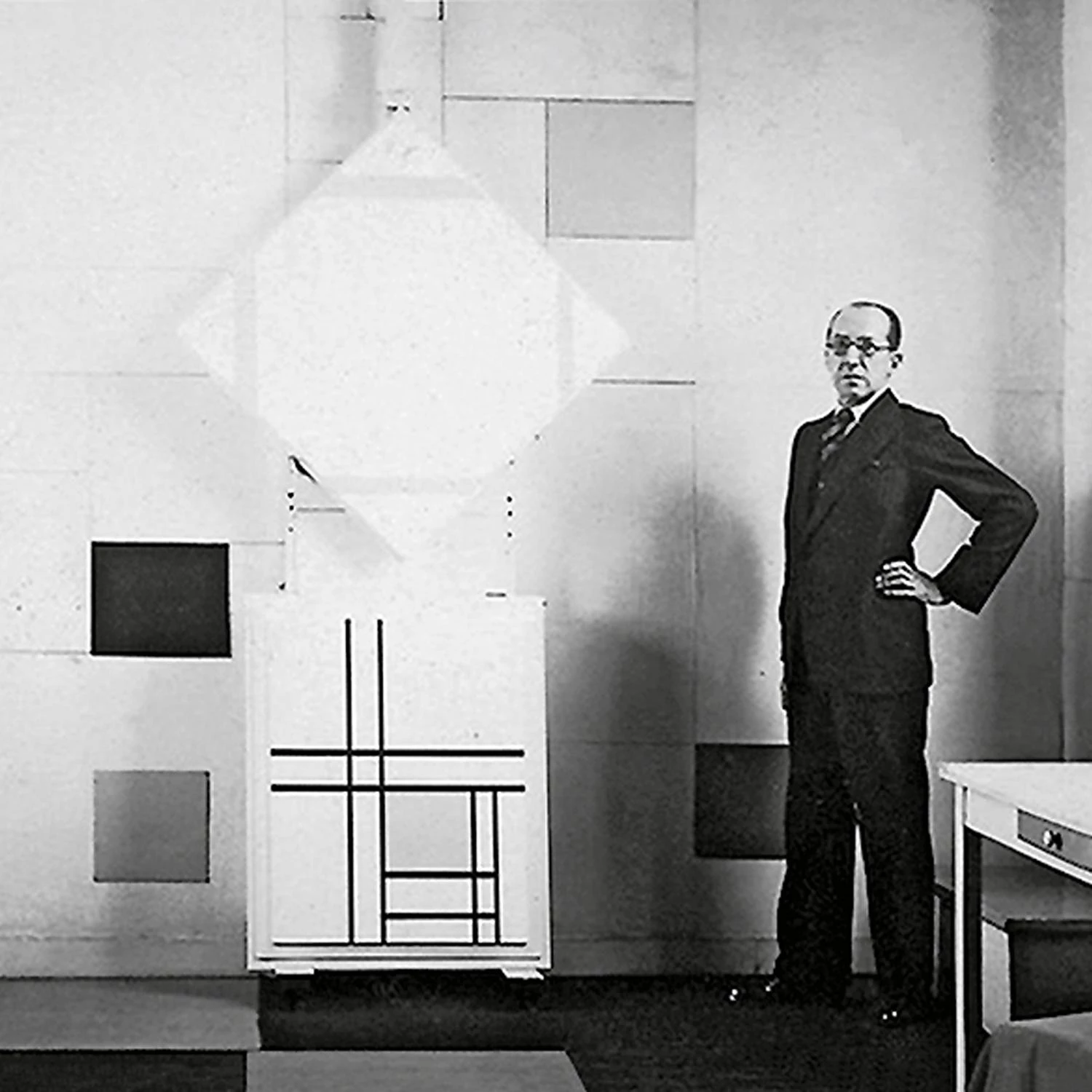

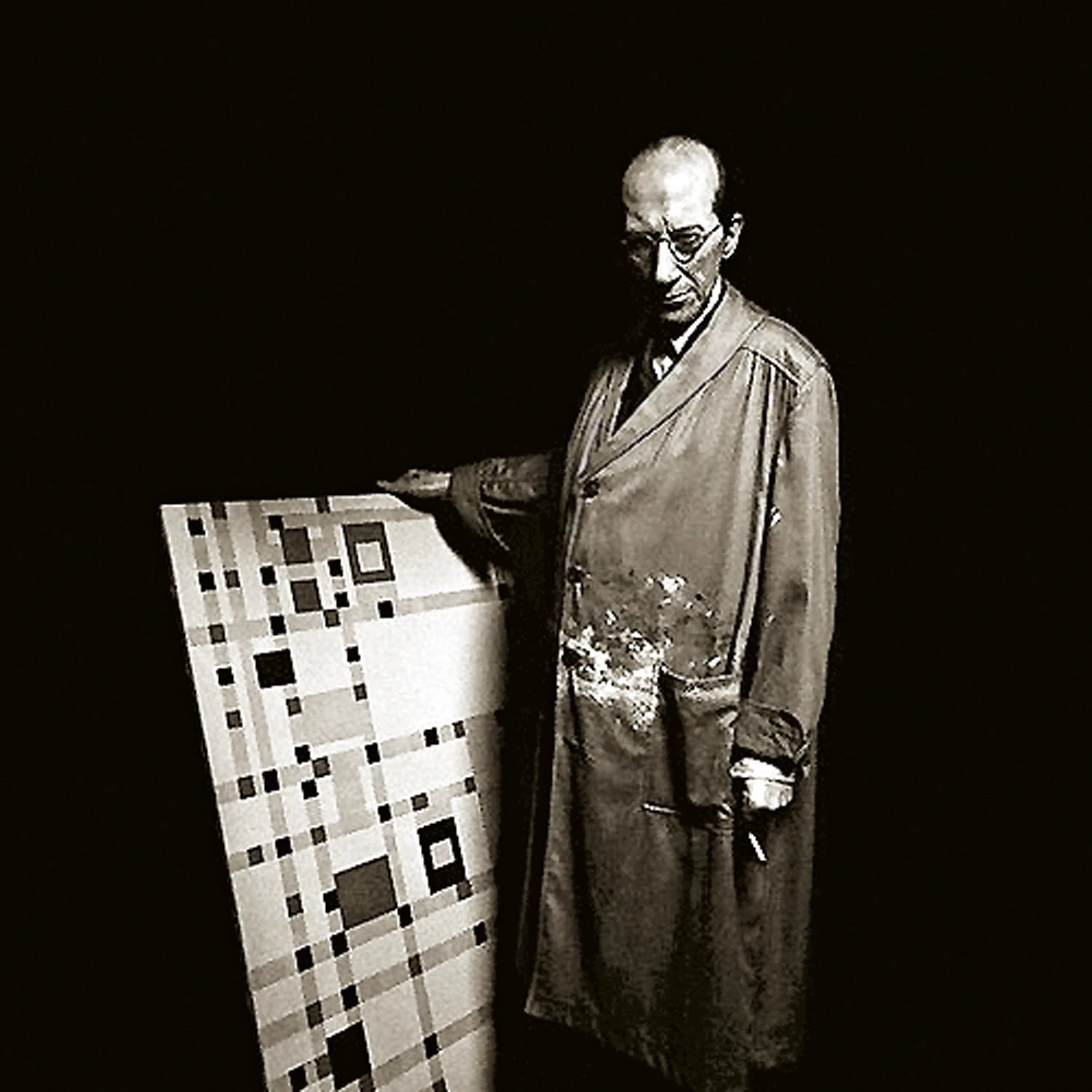

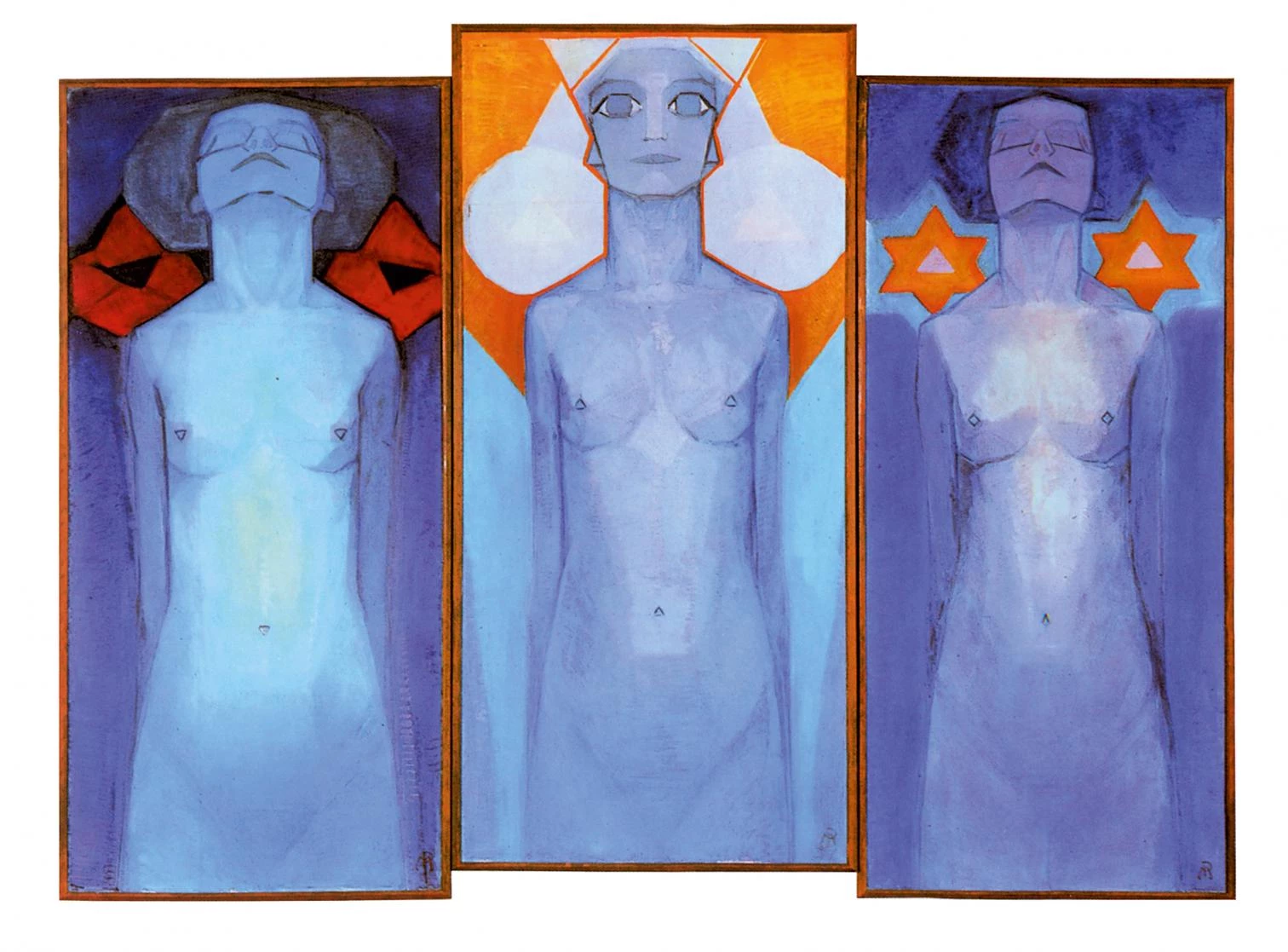

The doctrinaire fundamentalist, capable of breaking up with a friend for the heretical use of a diagonal, or of painting tulip leaves white in order to banish green from the neoplastic rigor of his Parisian studio, was, fortunately for him and for us, a lover of architecture and music, a bit of an interior designer and very much a dancer. When those two rhythmic arts guided his brush and his eye, he produced the incomparable works that range from the severe compositions of the 1920s to the magical hustle and bustle fun of the extraordinary Broadway Boogie-Woogie of 1943; when, on the contrary, he tried to give plastic expression to theosophic literature, his art went down in the painful abyss of his Evolution triptych of 1911.

Unlike the painter of Umberto Eco’s novel, who goes from geometry to symbolism, Mondrian abandoned symbolist realism for geometric abstraction; Jacopo Belbo would have corrected us: he abandoned symbolist abstraction for geometric reality. The latter, I believe, is the only Mondrian that Belbo and I understand; and the only one we can forgive for striking down heretics, painting tulips white, and even writing theoretical essays.