The Big R and the Small g

57th Venice Biennale: the Political Economy of Art

As Venice loses more residents each year, it compensates with increasing art venues. During the period of the Biennale, from May until November, the famously flood-prone city is literally swamped in art. Among the leading promoters are the relatively new institutions founded by two of the most powerful contemporary art consumers in the world: Miuccia Prada (Fondazione Prada at Ca’ Corner della Regina) and Francois Pinault (Palazzo Grassi and Punto della Dogana). But there are many other important players, including the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Palazzo Fortuny, Fondazione Cini, Palazzo Grimani, and a dozen others. The annual Biennale exhibition, which alternates between art one year and architecture the next, offers one of the most coveted occasions for an international elite to display their connection to the fickle world of art of today, while generating an audience estimated at half a million to supplement Venice’s already ponderous tourist trade of 30 million visits a year.

This year’s art Biennale, ‘Viva Arte Viva,’ organized by the French curator Christine Macel, who for twenty years has worked at Centre Pompidou in Paris, has the good fortune, or more likely misfortune, of being paired with a blockbuster exhibition, Damien Hirst’s ‘Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable,’ installed at both of Pinault’s venues. Thus the world’s richest artist (worth over a billion euros) has produced the world’s most expensive show (cost not disclosed, but in materials alone – bronze, lapis lazuli, jade, gold, pure white marble – easily 50 million euros) for the wealthiest collector (worth ca. 19 billion euros, and owner of Christie’s auction house), all of which would make any class-conscious observer puke! Here we have a reification of what Thomas Piketty in Capital in the Twenty-First Century defined as the ‘Big R’ (for rentier), the hoarding of non-productive capital by the richest 1% of the planetary population.

The Art of the little ‘g’

Although probably not intended, Macel has opted to favor the ‘little g’ (growth through productive capital) in her exhibition, placing the emphasis on the artist’s process, which includes the ancient concept of Otium (time away from the economic world), and features numerous installations that allow contact with people making things; the prime example is the major space of the central pavilion in the Giardini, which features two dozen refugees and anyone who wants to join them working on Olafur Eliasson’s Green Light Project, assembling green sticks into polyhedron lanterns. Donations for the lamps (250€) go to supporting the NGO organizations working with refugees.

Another way to involve visitors with artists occurs once a week, when a select audience is allowed to join one of the people featured in the Biennale at lunch to discuss the meaning of what they do. Macel also has converted James Stirling’s bookstore in the Giardini into a library of books selected by the artists in the show. As if to combat the speculative trends of the art market, the curator has relied on artists well known to herself but aside from Eliasson not household names, avoiding the celebrity factor, which risks leaving a very low profile.

Indeed when I attempted to recall what I had experienced after going through the Arsenale, I kept thinking of Marcel Duchamp’s 16 Miles of String, as there was a lot of yarn wrapped around things in works such as Mending Project by Lee Mingwei, which involves tailors repairing clothing by using colored threads attached to spools on the wall, the huge colored balls of woven cloth by Sheila Hicks, or the stunning tapestries of Teresa Lanceta.

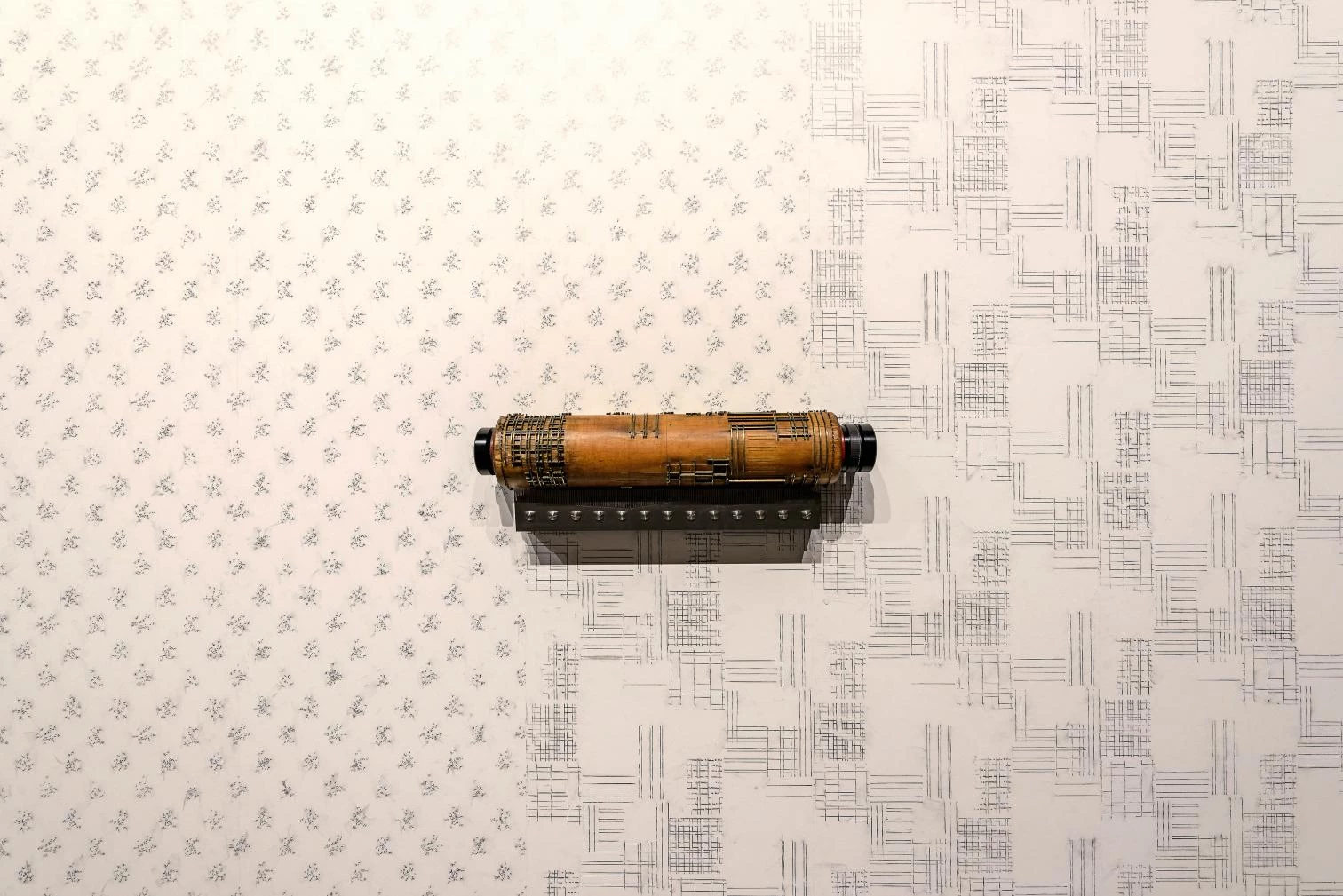

Indeed, the Golden Lion for best artist went to Franz Erhard Walther, who specializes in brightly colored cloth sculptures that can take unexpected shapes. In contrast to the investment portfolio needed to make the works of Hirst, Walther reaffirms the notion that artistic ingenuity means making something out of nothing. Wallpaper also came to mind during the stroll through the hundreds of works, due to recurring versions of serially repeated icons printed on the vast empty surfaces.

The most intriguing of these wall coverings came from two Albanians: Anri Sala, who printed the wall with the pegs of a player piano roll, and Edi Rama, current prime minister of Albania, who made a series of colorful tattoos. Sala got his start painting polychromatic buildings when Rama was mayor of Tirana.

Of the few old-timers in the show, a place of honor was reserved for the late Maria Lai (1919-2013), the eccentric Sardinian artist whose work and performances often involved threads, ropes, and books. Next to her display was a revival of the grand circle dances of choreographer Anna Halprin from San Francisco. The most painterly of the featured artists was Marwan (1934-2016), a Syrian who moved to Berlin and studied with Georg Baselitz, achieving an analogous expressionist style.

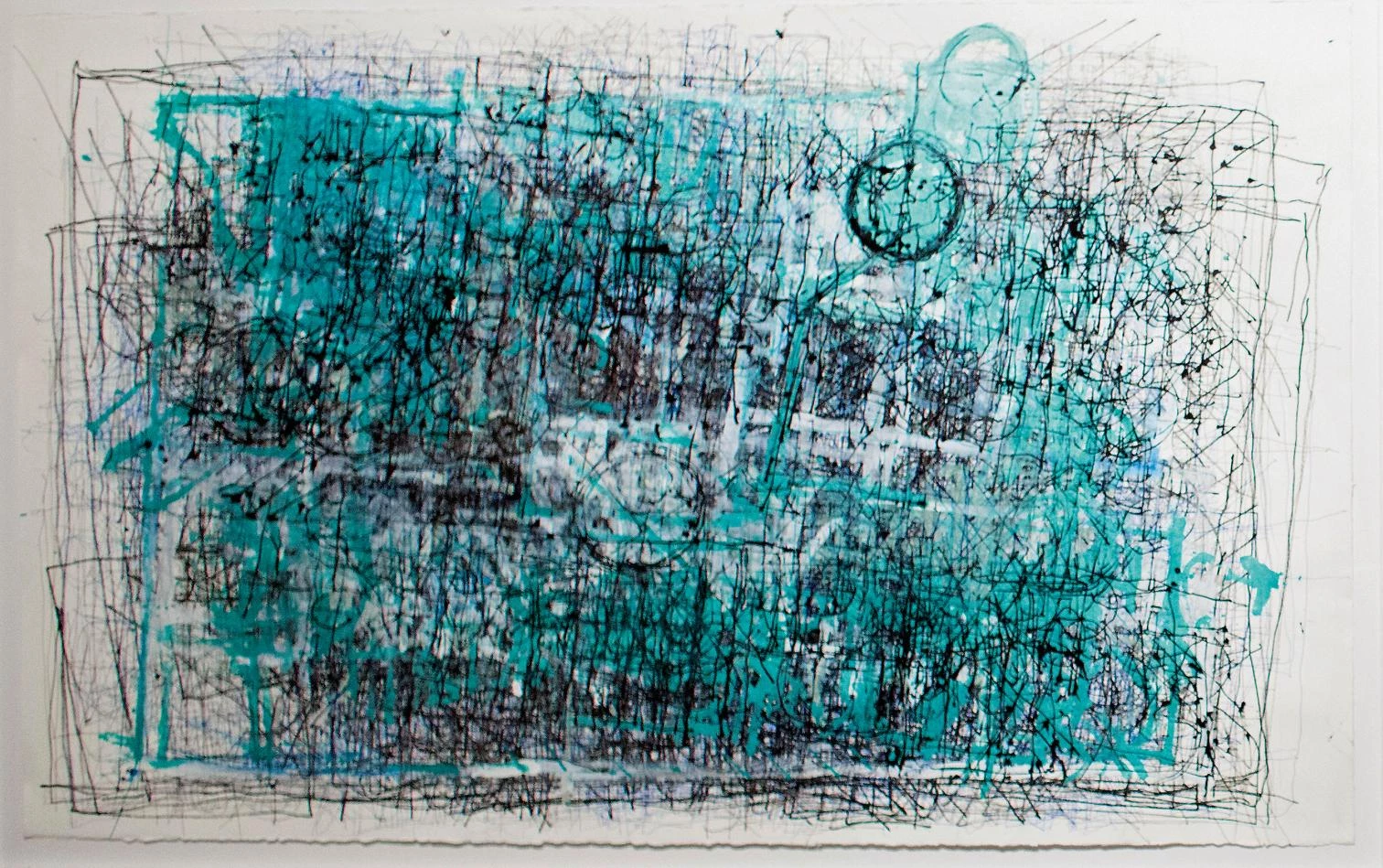

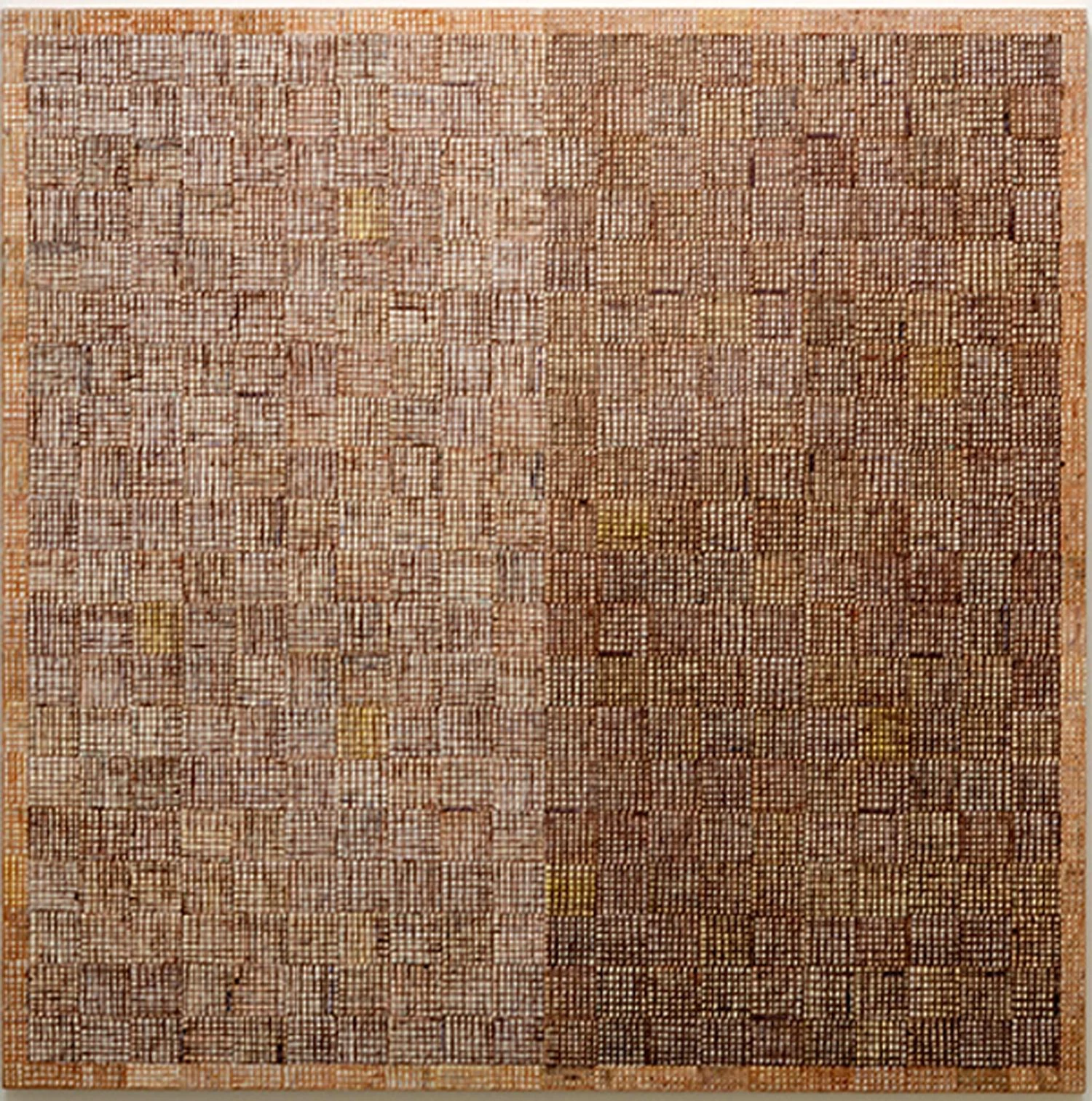

Littered amid the mostly conceptual projects were a few artists who still believe in making paintings, mostly Americans: McArthur Binion from Chicago, who works exclusively with meticulously delineated grids; Kiki Smith, who sketches large-scale female figures with pencil on casually pieced-together butcher paper, and ‘outsider’ Dan Miller from Oakland, who though afflicted with a form of autism has achieved a sublime abstract style of scribbled words that has an uncanny resemblance to Peggy Guggenheim’s protégé of the 1950s, Tancredi Parmeggiani.

Architectural Echoes

Many of the works bordered on architecture, landscape, and urbanism, such as Bonnie Ora Sherk’s Living Library projects, represented in hand-drawn panels that describe her efforts to occupy the residual spaces of infrastructure in San Francisco and New York City with citizen-managed gardens, or Michel Blazy’s two excursions into botanical extravaganza, one a vegetable tableau made from a collection of tennis shoes, strung on vertical ropes, filled with soil, and planted with herbs and flowers, and the other a series of brooms set in a spiral, apparently held in vertical position by the grass growing into their straw base.

One work hidden in the Garden of the Virgins that may be overlooked by most visitors is the Shipyard, a magnificent timber triumphal arch built by Michael Beutler from Berlin, who joined the grand 4-meter-high structure without nails and instead of setting it on foundations, floated its four piers in water-filled basins. The Silver Lion for the most promising young artist went to Hassan Khan, who created a sound garden with a series of speakers on poles. But my favorite was undoubtedly the Japanese artist Shimabuku’s pairing of Stone Age shards with cell phones and his video in which he sharpens the edges of a laptop into a more useful tool.

Many of the national pavilions had obvious architectural themes as well. The Spanish pavilion, for instance, begins with a series of identical cardboard boxes set on everyday tables, each printed with details from buildings that we later learn came from the structures built for tourists. The other rooms present a patchwork of videos set in Barcelona, Athens, and Kansas City depicting a fictional popular movement that begins with an evocation of the flight from Bethlehem and proceeds toward the temples of democracy in Greece and the USA. The French pavilion was transformed by Xavier Veilhan into an exquisite acoustic environment, entitled Musical Merzbau, in homage to Kurt Schwitters, and set for regularly scheduled recording sessions. Canada allowed the installation artist Geoffrey Farmer to remove parts of the roof while the pavilion is under restoration and let a geyser-like fountain spray up through its frame. Egypt’s Moataz Nasr built an adobe wall and provided an earthen floor as his theater for screening a multi-image film set in a peasant village. Israeli artist Gal Weinstein grew mold and rust on the walls and floors of the pavilion for his Sun Stand Still (a famous expression of Joshua’s need for more daylight to win the battle of Jericho), and using old coffee grounds created a scale model of the fertile landscape of the Jezreel Valley, inferring that political time and natural time do not usually coincide.

The Golden Lion for a national pavilion went to Germany for Anne Imhof’s performance known as Faust, the most intriguing aspect of which was the complete reflooring of the pavilion with thick glass sheets set a meter above the basement, while the performers moved in zombie-like ways both over and under the floor. Denmark made the most beautiful transformation, opening half of its pavilion by removing doors and windows, allowing artist Kirstin Roepstorff to turn it into an enchanted garden.

Some countries indulged in the return to art as the making of images, in particular Rumania, which featured the gracefully naïve work of Geta Br?tescu. Belgium offered dark, nearly imperceptible photographs by Dirk Braeckman. The grand video tableau by the New Zealand artist Lisa Riehanais is a reflection on colonialist vision that extends for 30 meters. And there are the captivating abstract assemblages and canvases of Mark Bradford from Los Angeles in the US pavilion. I would feel no differently about the value of Bradford’s work if I did not know that he was a gay African-American activist who uses the proceeds of his work to help foster children in the South Central ghetto of his hometown and has committed to help a cultural program for female prisoners in Venice for six years. The works of Bradford are astoundingly beautiful, some assembled from the cast away hair dye papers used in his mother’s beauty salon, others combining string and paint on enormous canvases with an impeccable knack for composition. For me a star is born.

Necrophilia and Boycott

The Italian Pavilion, featuring three artists inspired by anthropologist Ernesto de Martino’s Il mondo magico, provided the biggest surprise. The video by Adelita Husni-Bey asks a group of millenials in New York to struggle with the meanings for the future found in a series of tarot cards; Giorgio Andreotta Calò presents a field of scaffold columns that are holding up a huge surprise that one will have to decide what to make of after climbing up some bleachers to have a look – is it liquid or solid?; and most prominently, Roberto Cuoghi’s Imitation of Christ is a sort of Frankenstein laboratory where a cast of a young man has been prepared in resin, and a group of assistants regularly pours into it a gelatinous organic substance that solidifies into convincing replicas of the body.

These Christ-like figures are stored in inflatable igloos set at different temperatures, allowing the material to decompose in different ways. The assistants then attach the resulting fragments to the back wall as relics of the process. Such a detour into necrophilia provides one of the truly disturbing moments in the Biennale, an unforgettable experience that is difficult to accept, understand, or enjoy.

Did Christine Macel’s Biennale prevail over Hirst and Pinault’s presumption? Would you prefer to witness refugees making lamps and lots of talented use of yarn and wall paper, or verify that the 18-meter-high statue in the court of Palazzo Grassi, The Demon, really appears like bronze (it was assembled in sections of resin, and then given a bronze-like patina)? Will your imagination run with Hirst’s fictional archaeological conceit, replete with underwater videos of the presumed ‘find’ of the loot of a 2nd-century shipwreck off the coast of Africa, or will you prefer to find transcendent moments with the work of artists who stimulate your imagination with the simple play of light and shadow? We’ll have to see who sells the most tickets, but if I had my way, I would organize a boycott against the ‘Big R.’