The Venice Biennale, which every other year features architecture, has over the past decade provided an international platform for architects to attempt to redeem themselves from the common notion that they are at fault for such problems as deteriorating environmental quality, socially alienating spaces, and the overall ugliness of the contemporary city. From Massimiliano Fuksas’s curation in 2000, known as ‘Less Aesthetics More Ethics,” to Rem Koolhaas’s penultimate effort, ‘Fundamentals,’ in 2014, the struggle between the desire of architects to do the right thing and the political- economic system’s directives to do the reverse have been more or less evident. This year’s exhibition, however, curated by Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena, intends to beat the system. Well known as a ‘social’ architect specializing in sites-and-services projects that people with modest means can complete on their own, Aravena has gathered many like-minded proactive designers whose overall goals can be termed ‘environmental justice.’

Although the overarching title, ‘Reporting from the Front,’ suggests a context of warfare, the battlefields are not necessarily military encounters, but serve as metaphors for generic struggles such as segregation, pollution, migration, quality of life, sustainability, informality, traffic, and natural disasters. With few exceptions the architectural artifacts on display come from social mobilizations that usually define the architect’s role as more of a service than design. This focus on mutual aid does not exclude design, however, which can be admired in Wang Shu’s stunning mosaics made from the spoils of historic buildings in China as part of the Fuyang Museum, or in the bottle-encrusted adobe wall that recreates the atmosphere of the women’s shelters in Senegal and Tanzania, by the Finnish office of Hollmén, Reuter, Sandman, but it avoids presenting design as an autonomous discourse. Aravena has expressed his desire that all struggles lead to elegant solutions by using Bruce Chatwin’s photograph of the archaeologist Maria Reich perched lyrically atop a ladder in the midst of a desert. Unable to hire an airplane, it was her impromptu answer to the cosmic quest to view and understand the Nazca lines in Perú.

At the entry to the Arsenale’s gallery of the Corderie Aravena has launched a moral imperative: the decor was created by recycling 100 tons of materials from the previous Biennale, including a wainscot constructed of chunks of plasterboard, stacked like staggered bricks, and, dangling from the ceiling just above head height, thousands of slightly bent metal studs. The waste of one show has been transformed into the virtuous display of the other, but who knows what will become of the 100 tons afterwards. The curator has forbidden the waste of artificial compartments in the Arsenale, forcing the works of the 75 architects to create by themselves the necessary division and rhythm. So Rural Studio of Alabama has improvised an enclosure for their work made with linked bed frames, which will go to a community project in Marghera after the Biennale. Mumbai Studio, known for involvement with craftspeople, created an instant shelter using a frame of metal rods, draped with hemp blankets and plastered with an Indian specialty, cow dung, which, unknown to local health authorities, has dried into rigid surfaces!

The attention to recycling that begins at the entry gets more detailed in the ‘History of Waste’ installation by the young Polish architect Hugon Kowalski, who after doing research on how materials are recuperated in Mumbai turned his mind to European building products, attempting to reveal their performance in terms of the ‘cradle to cradle’ circular economy. Here you touch new synthetic materials (Stone-cycling, Smile-plastics, Derbigum roofing, inno-therm insulators, Mohawk flooring) and learn what percentage is made from recyclables and what optimal rate of recycling the product can yield; Sus-con, a new concrete made of 100% recycled materials, performs best, while Marley Eternit refused to answer the survey. In sympathy with recycling, the final bay of the Corderie includes a tribute to the recently deceased Nek Chand, creator of the ‘Rock Garden’ at Chandigarh, where over sixty years he sculpted hundreds of totem figures, turning cast-off materials into joyful park settings.

Perhaps the most impressive visual impact of the show came from the ETH Zurich team led by Philippe Block, ‘Beyond Bending,’ which extended a grand ‘armadillo’ vault of digitally cut limestone blocks across 16 meters without the help of reinforcing rods or mortar, its parametrically obtained irregular curvature completely reliant on compressive forces. Using a large 3D printer the same team also demonstrated how the strength of concrete can be matched with sand and polymers as an ideal flooring structure. The Golden Lion for an individual went to another structural project, one created by Paraguayan architect Solano Benítez more in the spirit of Maria Reich, without computers and thus more accessible to self-built situations. Using a falsework of plywood panels, he raised a grid of X-shaped ribs into a parabolic vault and then distributed the panels around the room as decoration. Until we all can afford 3D printers, this seems a more accessible method of spanning space.

A Starless Biennale?

While most of this Biennale prides itself on anonymity, collectivity, and process, there are architects with strong personalities, especially in the Italian Pavilion in the Giardini, yet somehow their work got subsumed by the modesty of the rest. Grafton Architects of Ireland, who built a heroic university structure in Lima, a concrete structure worthy of this year’s winner of the Golden Lion for lifetime achievement, Paulo Mendes da Rocha, is represented by a film emphasizing context rather than design. Aires Mateus of Portugal is tucked into a corner where it is easily missed. Special mention in the awards went to Giuseppina Grasso Canizzo, who works on superb small projects in Sicily and here hung a curtain-like enclosure of small panels on chains that describe in drawings and photographs her intimate works.

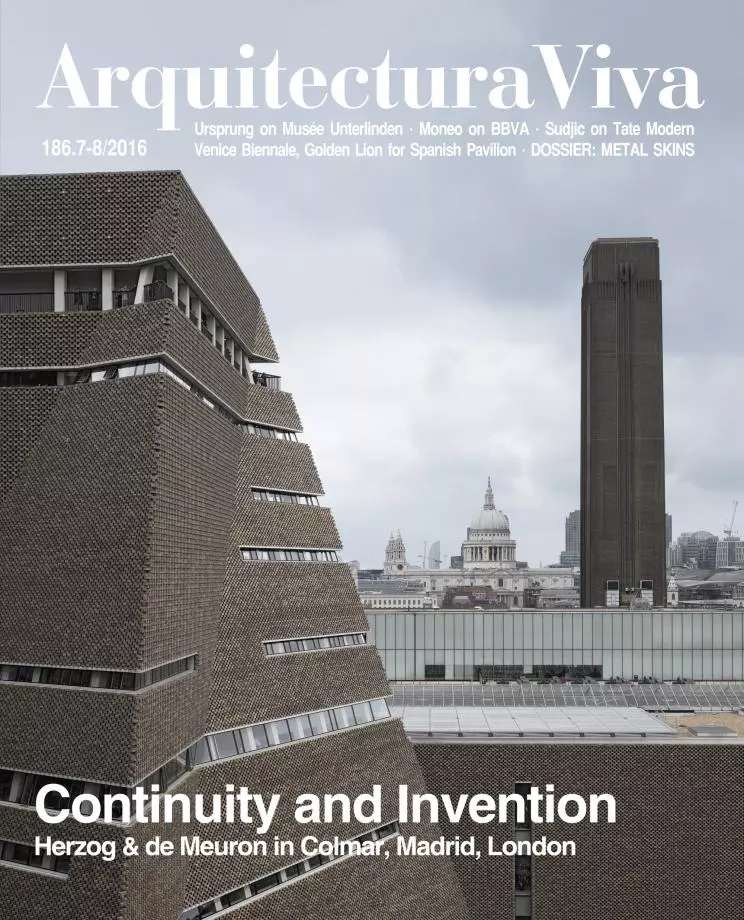

Aravena also included a few genuine stars: Foster, Piano, Rogers, Chipperfield, Seijima, or Herzog & de Meuron, but they also, either by default or choice, get little attention. The last mentioned Swiss architects appear in a postdocumentary film by Amos Gitai, hidden in one of the vaulted storehouses at the far edge of the Giardini delle Vergini. An amusing slippage: Rogers placed next to Piano (ex-partners and still good friends), where the former states that “suburban sprawl feeds climate change,” offering stacked containers assembled like a vertical Habitat with trees growing on it, while the latter defends the periphery, where he has been using his senatorial salary to finance young architects in the process of ‘mending’ the suburbs, where majority of the urban population resides.

Norman Foster participated more as patron than designer, his foundation financing one of the most ambitious constructions of the Biennale, a full-scale version of a droneport for remote parts of Africa, made of a parabolic pitched-vault technique reminiscent of Eladio Dieste’s work in Uruguay. Philippe Block worked on the structure, which, while more complex than Benítez’s vault, has the same potential for self-builders. With the best of intentions the droneport remains a high-end product to house a high-tech instrument, which might invite humanitarian functions but more likely will have military consequences. More accessible and even more spectacular is the reconstruction of the floating school of Makoko at Sansovino’s Gaggiandre dry docks. Designed by Kundé Adeyemi, awarded the Silver Lion for promising young participant, the A-frame structure sits on recycled steel drums and scavenged wood and anticipates changing water levels for a community living in informal houseboats.

Benevolent Activisms

One of the genuine amusements of the Biennale is to discover how each of the 65 national pavilions responds to the theme. Germany’s ‘Making Heimat’ matched Aravena’s brief earnestly, confronting the sensitive ‘front’ of immigration by removing some of the walls of the pavilion and promoting the idea of the ‘Arrival city’ to welcome, care for, and integrate newcomers. Italy’s show, ‘Taking Care,’ likewise chose to focus on emergency architecture, asking five offices working with five citizen associations to prepare prototypes that can bring services to communities in need, from health care stations to mobile libraries.

Belgium, as in other years, slightly transcended the theme with a high concept, presenting six full-scale architectural details that were curiously anomalous to their sites shown in photos. Each of the projects somehow addressed a social problem, ranging from the placement of a mailbox to an affordable living space made with hay bales for a wheelchair-bound person.

Other pavilions mixed a political discourse with play, such as that of the Netherlands, which catalogued UN peace-keeping settlements, provided a circular sandbox in the center where children could build sand castles. Australia provided an indoor wading pool to address the importance of swimming pools in community formation. Israel shifted its ‘front’ from the obvious zone of conflict to that of biomimetics, creating a space that looked like organic tissues and provided detailed analogies between biology and construction. The Nordic Pavilion, ‘In Therapy,’ supplied 19th-century chaises longues typical of Freudian psychiatry and a screen in which an architect attempted to analyze the fate of architecture in Scandinavia. Russia seemed the farthest from any ‘front,’ offering a description of the Stalin-era VDNH, theme park of national achievements, a strange sort of preservation project for the most retrograde culture of the Soviet era. Even China, which seems to be choking with overdevelopment, created an exhibition devoted to the conservation of the culture of rural villages, displaying fascinating garments woven in traditional settings.

So if there is a fault at this year’s Biennale, it is excess of virtue, a panoply of benevolent activism in a world that usually appears cruel, self-centered, and destructive. Only a few instances could break the spell: Eyal Weizman’s disturbing research, known as ‘Forensic Architecture,’ which presents spatial evidence of human rights violations, such as ‘Death by Rescue’: the EU’s non-assistance to the boat people of the Mediterranean. Or self-indulgent experiences, such as the Montana desert constructions of Ensamble Studio, of Spanish émigrés Antón García- Abril and Débora Mesa, who return to the exploits of land artists Robert Smithson and Michael Heizer to make monumental concrete monoliths. Even more shocking in its rejection of the ‘front’ is the Swiss Pavilion’s ‘Incidental Space’ by Christian Kerez, who in the main show virtuously pursues the analysis of informal housing in Latin American cities, but here creates an object of pure form, aloof from social issues. The uncanny object, which appears like a taihu rock, or the baroque cloud under Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, was generated through computer models based on the point cloud scanning of dynamic particles like sugar and dust that were then boosted in scale and cast in plaster panels of sprayed fibercement two centimeters thick, and adjusted with plotting and milling techniques to replicate the form of the model. This imitation of nature, achieved through unnatural processes, offers its hollow interior as a degenerate child of Friedrich Kiesler’s ‘Endless House.’

The ‘Spanish Solution’

That the Golden Lion went to the Spanish Pavilion, ‘Unfinished,’ seems an obvious choice, as here one finds great attention to good design. While the social and environmental fronts are implied by the projects chosen, the curators Iñaqui Carnicero and Carlos Quintáns have selected works that impress one about fitting, reusing, and adapting with charm. The central hall features skeletal metal studs, like unfinished buildings, that hold photographs of ruinous landscapes, products of the real estate bubble. In surrounding rooms the metal studs are transformed into tables showing one plan and one photograph of 55 projects that harmonize the rough edges of the crisis. The curators’ attack on the excesses of real estate and ‘starchitecture’ leads to a theory of resistance, a return to modest craft described by Quintáns in what could be a manifesto for the ‘Spanish Solution’:

‘Unfinished’ is a moment for reflection about architecture that is born to be used and transformed, that is born and lives with change. Architecture doesn’t renounce the completion of the project with the highest level of coherence possible, but is aware that the result may be only a stage in this search for coherence. Architecture that solves real problems. The selection tries to discover and evoke the beauty of the collective. It tries to revindicate the urban environment as a source of guidelines; the result of the construction of successive actions and of layers of time. It no longer pertains to an expansive urbanism, but is inserted into the existing, consolidating disintegrated spaces and developing a sense of belonging to the place. The exhibition also proposes the transformation and occupation of obsolete, abandoned, or incomplete structures. It defends these guidelines as adaptation strategies. It shows generic spaces for a multiplicity of uses over time, spaces that allow the architecture to adapt over time. We are searching for an architecture that, although it needs to be built, also defends demolition, reduction of density, or regeneration with vegetation as architectural tools for intervening in inherited constructions.”

Using keywords they show how recent projects, mostly by young unknown firms, have pursued concepts like consolidation, reappropriation, adaptation, infill, reallocation, guidelines, and pavements. While this cannot cure the problems of the economy, it is a moral response to its causes.

Like the 2015 art Biennale curated by Okwui Enwezor, most of this year’s participants come from so-called nonwestern sources. A leveling of sorts is occurring. Yet in the current show the sense of charity or welfare rests as an undercurrent and the lack of healthy protagonism comes as a response. In considering the impact of Aravena’s Biennale one might return to Oscar Wilde’s caveat on altruism in The Soul of Man under Socialism: “… with admirable, though misdirected intentions, they very seriously and very sentimentally set themselves to the task of remedying the evils that they see. But their remedies do not cure the disease: they merely prolong it. Indeed, their remedies are part of the disease. They try to solve the problem of poverty, for instance, by keeping the poor alive; or, in the case of a very advanced school, by amusing the poor. But this is not a solution: it is an aggravation of the difficulty.” Such an awareness is why the return to normality and self-determination expressed in the Spanish pavilion and in several parts of the show are so important, because as Wilde concludes: “The proper aim is to try and reconstruct society on such a basis that poverty will be impossible.” And likewise with other factors, especially the environmental crisis. This reconstruction of society is the ‘front’ that Aravena attempts to reveal.