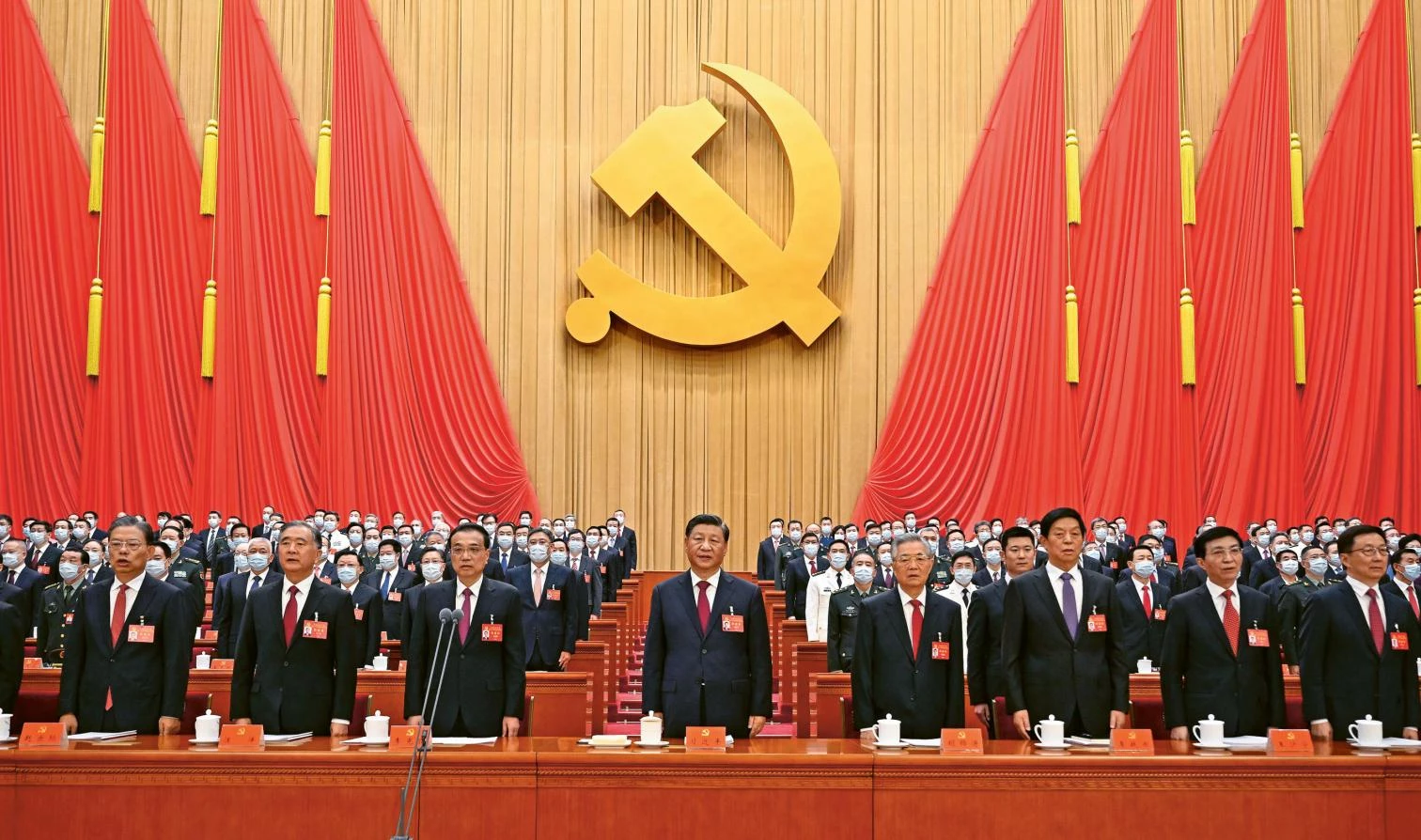

Hostesses serving tea at the opening of the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of China

The China of unanimous attendants is hope and threat. Hope because its achievements have radically improved the living conditions and self-esteem of the population, turning into a model for many countries; and threat because ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’ aims to replace the global order created by democracies with another that subordinates the individual to the collective, and freedom to security. In October, the Great Hall of the People hosted the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of China, which confirmed Xi Jinping for a third mandate of five years, making him the most important leader since Mao Zedong, and perhaps the most powerful person in the world. As much the changes in the Politburó and the Standing Committee as Xi’s speeches in the congress marked the new direction of Chinese politics, which has for years been replacing the emphasis on growth with the search for a ‘common prosperity’ where the State counterweighs the markets and the drive for self-sufficiency extends from energy and minerals to technology.

The course of the Asian superpower is marked in this century by four turning points: the admission of China into the WTO in 2001 boosted its growth; the Beijing Games in 2008 showed its rise to the world; the election of Xi to the presidency in 2012 extended its global influence through the Belt and Road Initiative; and the 20th Congress in 2022 signals the way towards a new global order, different from the current Western model. AV/Arquitectura Viva has tried to keep track of these shifts in several monographic issues: ‘China Boom’ in 2004, on its building frenzy; ‘Olympic Beijing’ and ‘Shanghai 2010’ in 2008 and 2009, covering the events that displayed its achievements; and ‘Made in China,’ ‘Eternal China,’ and ‘Material China’ in 2011, 2015, and 2018, showing the confidence of a culture that presents itself to the world as a referent. And today, after the celebration in 2021 of the anniversary of the Communist Party, commented in Arquitectura Viva 236 (‘A Centennial Dragon’), China emerges as a rival of our societies and our values.

Freedom of choice in consumer habits or behaviors, in contrast to uniformity in politics or life, has been depicted opposing a cheese tray to coffee for everyone. Tea for everyone in today’s China does not exclude the variety shown by the architect Wang Shu, the artist Cai Quo-Quiang, the writer Mo Yan, or the filmmaker Zhang Yimou, but it has left out figures like Ai Weiwei, and the plurality of voices within is only tolerated if, respecting the centrality of the party, the red lines of Taiwan, Tibet, and Tiananmen are not crossed. Josep Borrell, High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs and Security, has caused unease describing Europe as a garden surrounded by jungle, and claiming that we cannot be herbivores in a world of carnivores, but the Ukraine war – which has not altered the ‘boundless friendship’ between Russia and China – recalls the Venus and Mars dilemma. The clash of superpowers fractures the planet, and the truth is that we do not know well which is the best way to protect our garden.

The exact choreography of attendants serving tea at the 20th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party illustrates the social discipline and institutional harmony that Xi’s neo-Maoism tries to impose on the country.