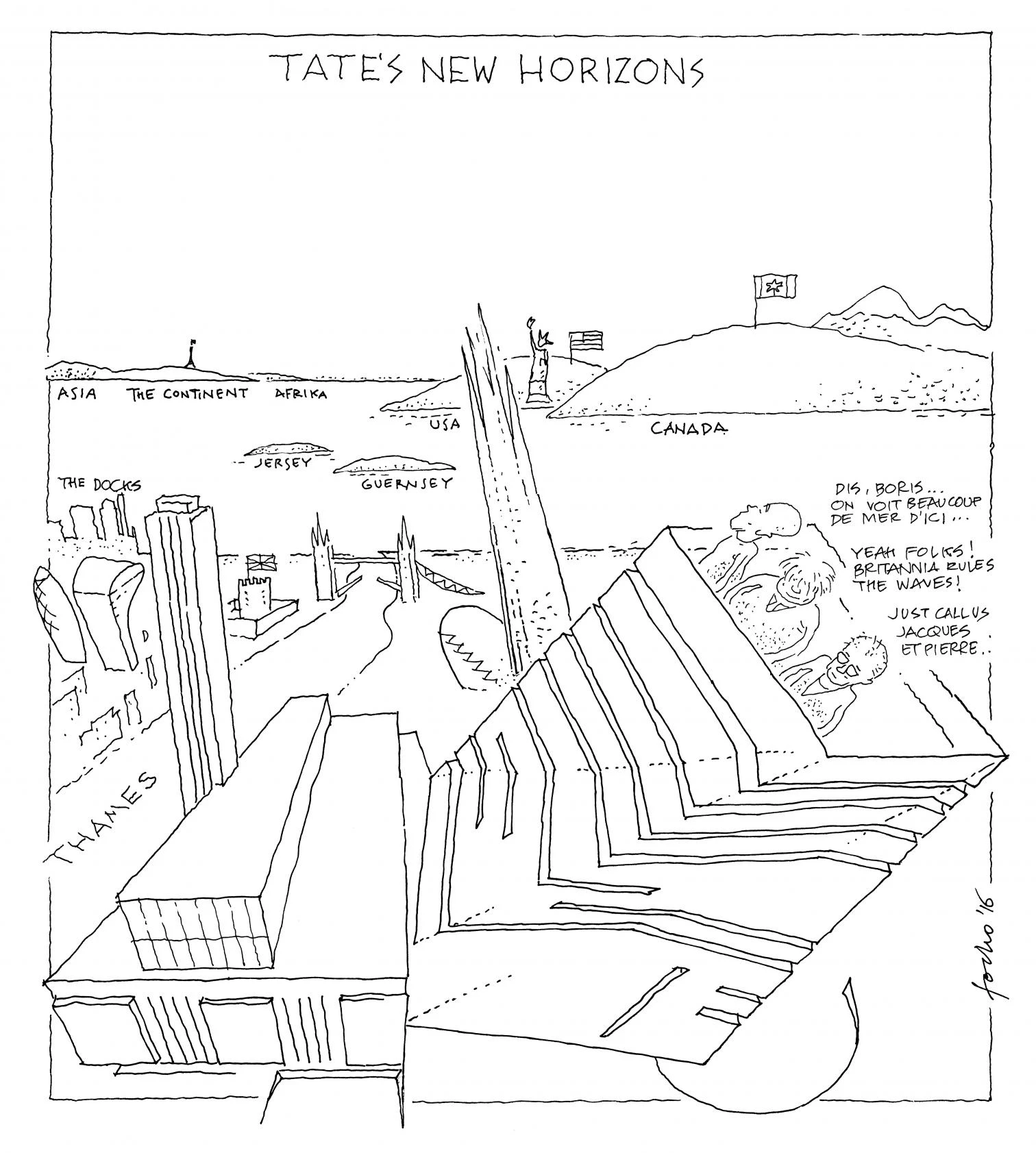

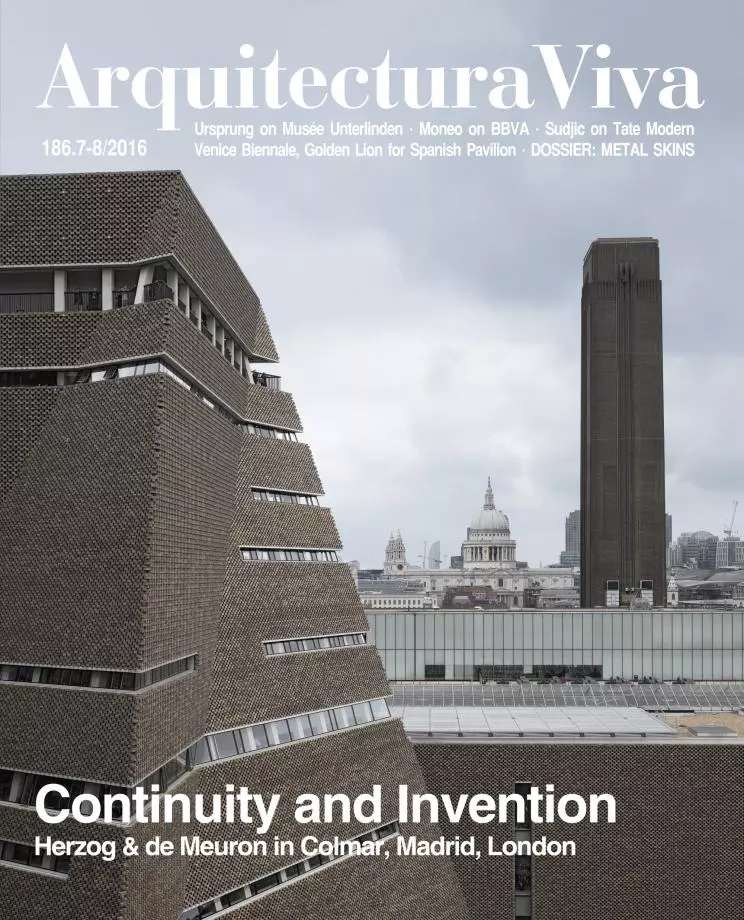

The contorted pyramid rose behind the brick cliff and hundreds of people laid siege on the building, eager to contemplate the new spaces and the new collection: the enlarged Tate Modern opened its doors just as the country’s polls were being readied for the referendum that days later would leave the United Kingdom out of the European Union. So what was perhaps meant as a celebration of London’s openness to world art markets – or of London’s cosmopolitanism – ended up a symbol of the tensions and paradoxes of a country that has never been fully comfortable in its relationship with the ‘Continent,’ and also of the tensions and threats (the widespread disgust with austerity policies, the growing movements of populism and nationalism) that are increasingly characterizing western societies, in particular the European Union, which never before has been as debilitated as it is right now. It is difficult to look at the new Tate Modern in the light of the serious developments of recent weeks, but sociology and politics should not cloud the fact that here stands a truly exceptional work of architecture, one in which its authors, the Swiss partners Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, have once again successfully responded to a tall order: to expand the museum’s exhibition floor surface area by a good 70 percent while maintaining the spatial dominance of the Turbine Hall and the iconic might that, with the change of use, the old power plant has taken on in its formerly impoverished urban context. The British critic Deyan Sudjic presents the main aspects of the project in the following pages.