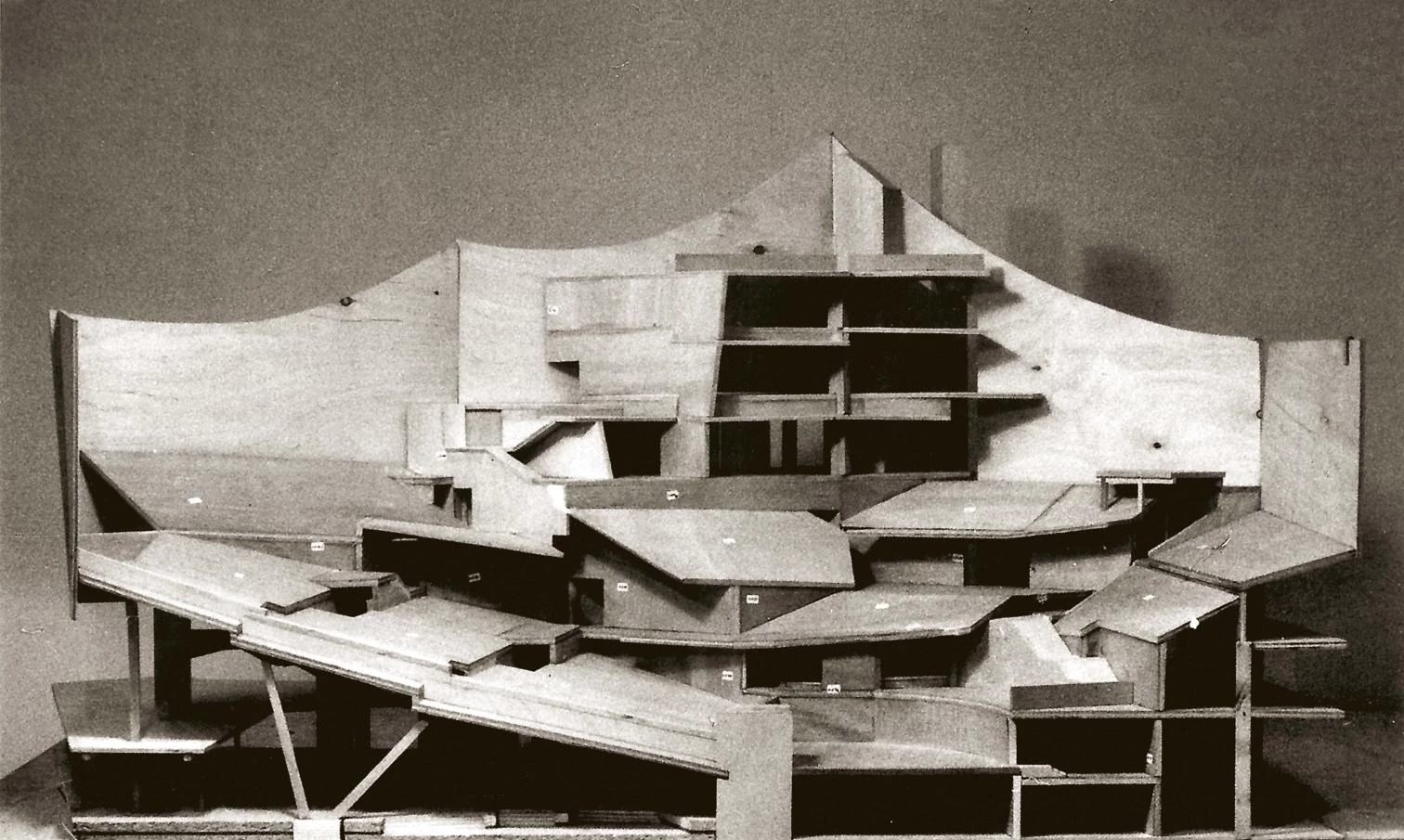

Buildings made for sound are also made for sight. My generation learned the rule that auditoria are constructions to be judged with one’s eyes closed, but in truth few buildings are enjoyed with such wide open eyes as those raised for music. Be they philharmonic spaces as the one Hans Scharoun built in a pioneering manner in Berlin – developing previous theater experiences in which the spectators surround the stage entirely, taking a role similar to that of the crowds in sports venues – or more conventional operas or auditoria where each seat is expected to offer good visibility, buildings for music serve both the ear and the eye; and all this without mentioning the equally essential function of seeing and being seen, in the auditorium or the foyer, spaces both that act as backdrop for the social choreography of meeting and greeting, and places therefore governed by sight.

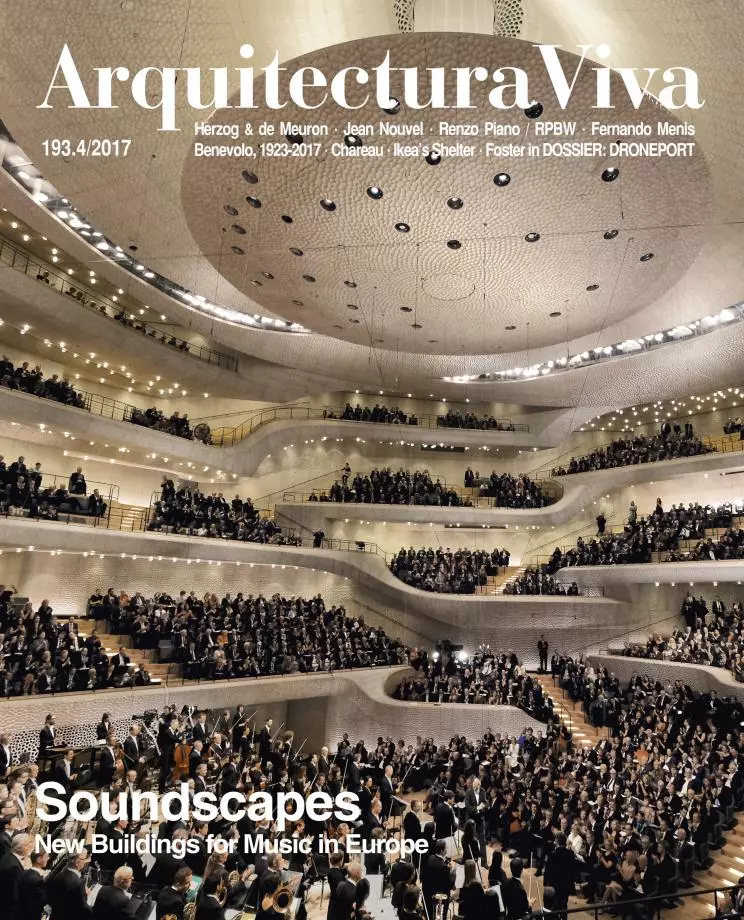

The eye is also the protagonist in concert halls when these serve as stage for audiovisual recording or broadcasting, a circumstance that today more often than not accompanies musical interpretation, and in this case the eye is that of the camera. At the recent opening of the Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg it was impossible not to notice the many cameras documenting the event, including the one overflying the audience moving on a trapeze-like cable – just like weeks before a drone had allowed to tour the entire building, perhaps encouraging to replace the Corbusian promenade with the vol architecturale –, a use of the spectacular space as a film studio that illustrates well the critical importance of the visual element in buildings for music, once the excellent experts in acoustics and the sophisticated previous studies and tests have guaranteed the optimum sound behavior of auditoria.

Always built for public attendance, in many cases large in scale, and often in prominent locations, constructions devoted to music usually have the added role of being city icons, landmarks in the urban geography that can function as drivers for regeneration and sources of collective pride, and this emblematic role also prompts to understand auditoria as visual artifacts. Though they must necessarily adapt to context, they also face the challenge of standing out with their characteristic forms, materials or presence in the skyline, so that they can produce memorable images where civic identities crystallize. For all the above, soundscapes are also visual landscapes: in the auditoria criss-crossed by gazes and cameras, in the relaxed or hectic foyers ready to be explored with feet or eyes, and – last but not least – in their deep impact on the urban environment and the symbolic universe.