Celebrations do not remember history; they fabricate it. Beneath the gleam of the New York exhibitions on Mies van der Rohe, the year 2001 tiptoed through the Louis Kahn centenary and mutely marked those of figures like José Luis Sert or Jean Prouvé, while almost completely ignoring Berthold Lubetkin, Alberto Sartoris, José Villagrán and Konrad Wachsman. What can we expect of 2002? For the ten figures born in 1902, we could forecast five episodes of neglect and five of tribute.

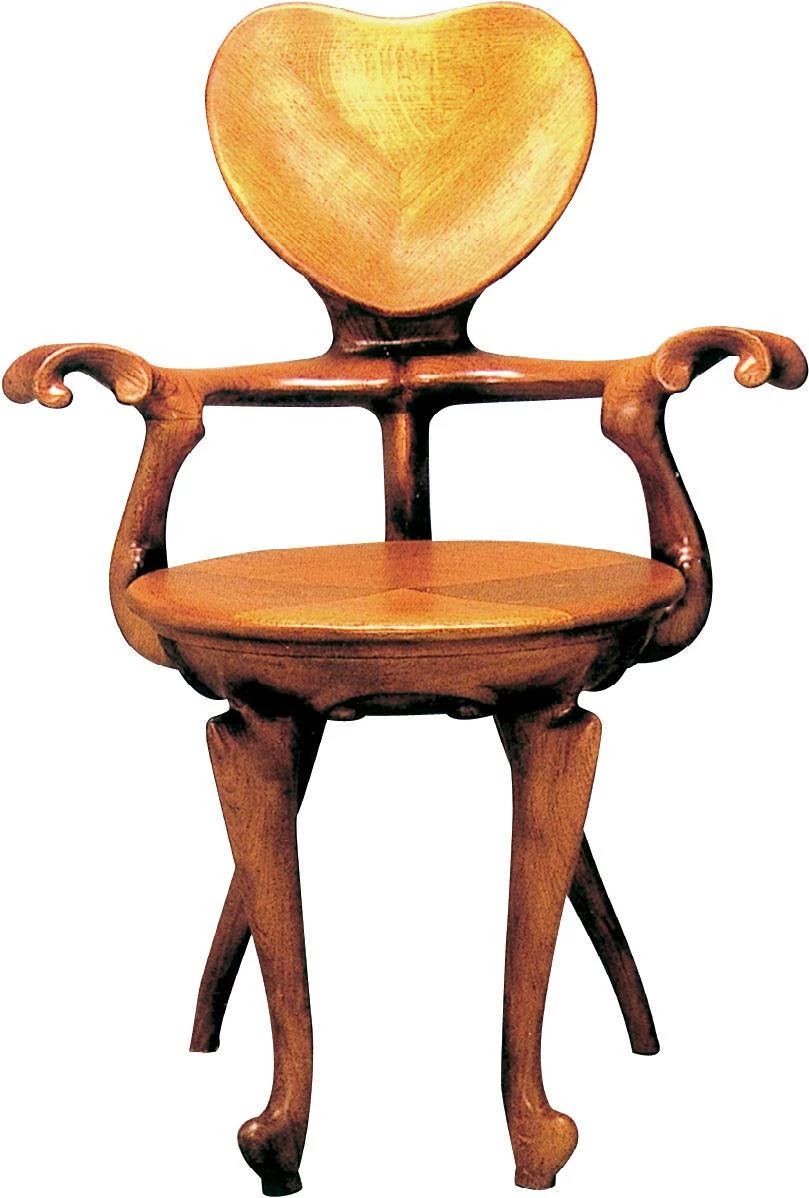

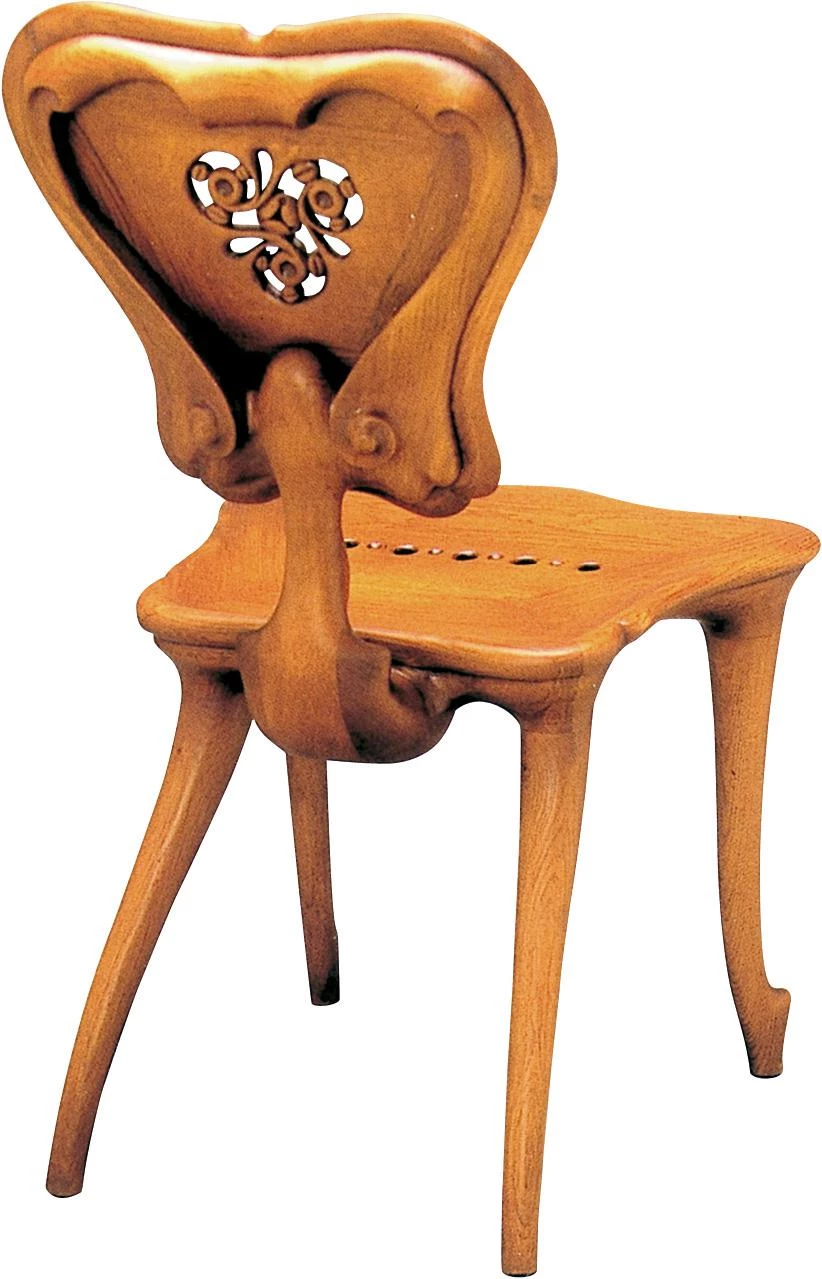

Barcelona celebrated the versatile talent of Antoni Gaudí with fourteen simultaneous exhibitions.

One is hard-pressed to imagine a resuscitation of the French Émile Aillaud, whose interminable loops of social dwellings tried to redeem, through color, the depressing monotony of destitute postwar peripheries. It is not fair to credit the Dutch Joannes Andreas Brinkman for the works he signed with his most gifted colleague, Leendert Cornelis van der Vlugt, among them the mythical Van Nelle factory of 1930, for which reason his centenary will better pass in silence. There is no need at this point to review the work of the Ukrainian-born American Morris Lapidus, because his recent death last year already occasioned, through obituary notes, abundant recollection of those scenographic Miami hotels of his that so fascinated the public in the fifties and post-modern architects in the seventies. We cannot foresee a revival of interest in the great Italian engineer Riccardo Morandi, ever in the Roman shadow of his brilliant compatriot, ten years his senior, Pier Luigi Nervi. And neither need we pay much attention anew to the cor-porate and bureaucratic work of the American Edward Durell Stone, as conventional in his international style work of the thirties as he was mediocre in his bland pax americana rhet-oric of the postwar period.

On the other hand, the first five months of the year register five successive centennials that cannot go unnoticed. 9 February is the anniversary of Ivan Leonidov, a visionary draftsman who captured the incandescent spirit of the Russian revolution in titanic Utopian projects. Two days later, on 11 February, Scandinavia and the world will honor Arne Jacob sen, a prolific designer of architecture, furniture and objects whose elegant exactitude marks the most optimistic moment of the modern movement. 27 February will be the turn of Lucio Costa, the great Brazilian architect and urban planner who directed his inquisitive talent to the physical and social transformation of his country, a project symbolically materialized in the construction of a new capital, Brasilia. 9 March will be dedicated to the memory of Luis Barragán, a mystical conservative who dyed his elemental geometries and severe textures with unexpected colors and yet produced demure, essential architectures. And finally, on 22 May, we shall commemorate the one hundredth year of Marcel Breuer, a Hungarian Jew who partook of the central episodes of the 20th-century avant-gardes, from the radical German Bauhaus to the domestication of modernity in his American exile.

Five architects of the same age, yet hard to consider contemporaries. Their lives coincided and there were episodic contacts between some of them, but it is difficult to think of the five as inhabiting the same historic time. Surely they exemplify what Georg Kubler explained in his methodological work, The Shape of Time: that chronological simultaneity does not signify historic proximity, because different times coexist and flow in a fluvial bundle that separates or mixes currents in an at once placid and turbulent course.

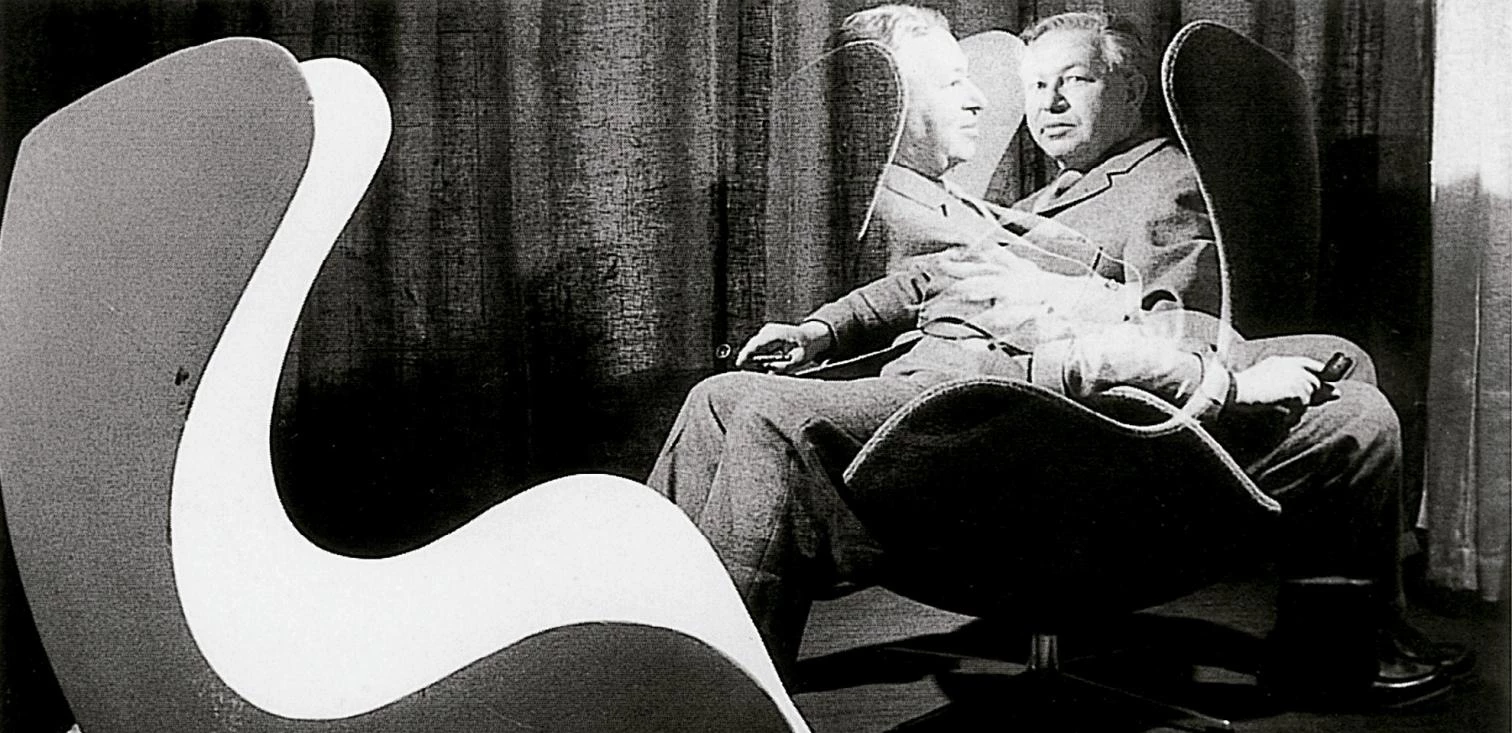

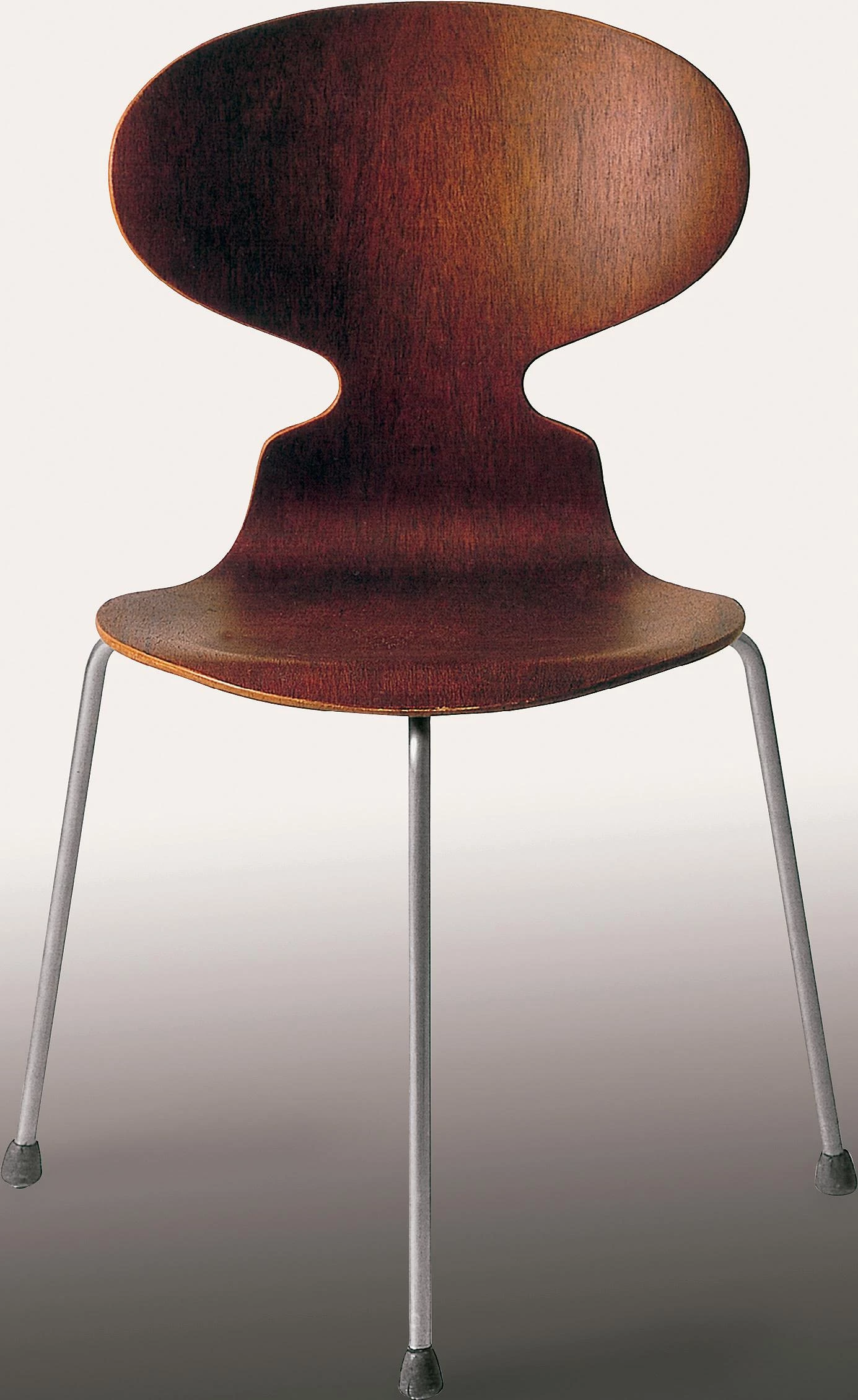

El prolífico Jacobsen (izquierda, sus sillas Hormiga y Sevener, y su sillón Huevo), el visionario Leonidov, el entusiasta Costa, el ensimismado Barragán y el comprometido Breuer (mas abajo, su poltrona B35, su silla B32 y su sillón Wassily) habitaron un mismo tiempo cronológico, aunque la diversidad de sus contribuciones a la modernidad hace difícil reconocerlos como contemporáneos.

The youngest of the Russian constructivists, Leonidov stepped into the history of the 20th century in 1927 with the Lenin Institute, his brilliant final project in the avant-garde school VJUTEMAS, a light sphere of glass and an immaterial prism tensed by cables and antennae whose muscular metaphysical lyricism instantly made it a suprematist emblem of the new revolutionary architecture. But after his 1930 proposals for Magnitogorsk, the Utopian linear city of Soviet egalitarianism, and the futuristic skyscrapers designed in 1934 for the Ministry of Heavy Industry, his star waned with the stagnation of the communist regime, and in 1959 the architect died in Moscow with practically nothing built.

In contrast, having made a name for himself with the ephemeral ‘house of the future’ project in the exhibition of the 1929 Copenhagen Forum, Jacobsen immediately set out to execute admirable works like the Bellevue beach complex, the Århus and Søllerød town halls, and the herring-salting plant on the island of Sjaellands, all of which would have ensured him a place in history even if his bizarre 1943 escape from the Nazi persecution of Jews had not been carried out with success. After the war he resumed in his country an usually fertile career that has left us exquisite buildings like the Hårby and Munkegård schools, the town hall of Rødovre, and the SAS hotel, plus furniture and industrial designs that with-stand the test of time like the Ant and Series 7 chairs, the Egg and Swan armchairs, or the Vola plumbing fixtures: the Scandinavian socialdemocrat luminous project of happiness, austerity, and comfort had no better intepreterthan this architect of routinary life, impeccable taste and astounding results.

Costa, in turn, made it to the century’s register with the education ministry building in Rio de Janeiro, a colossal project executed from 1936 to 1945 in conjunction with his compatriot Oscar Niemeyer, where Le Corbusier took part as consultant and inspirer, and which marks the foundational moment of Latin American tropical modernity. But his most lasting contribution is the map of his country’s new capital, Brasilia, a heroic manifesto of the modern confidence in technocratic planning and the city of the automobile, which he generously drew on the tabula rasa of the sertão in the shape of an airplane.

On the same continent, Barragán followed a path that was almost antithetical to the Brazilian’s. Intimist and self-withdrawn, this affluent, refined, and homosexual Catholic shunned public life to construct a short, late-coming, and intense oeuvre that transported modernity to the landscape, climate and vernacular traditions of Mexico through the filter of colonial and Spanish Islamic architecture. From the abrupt volcanic relief of Pedregal, an urban development of the 1940s, to the Capuchin convent or the Las Arboledas riding grounds of the 1950s, his abstract, material, and chromatic language was imbibed with a hermetic, archaic fascination that contained a promise of timeless serenity.

Luis Barragán

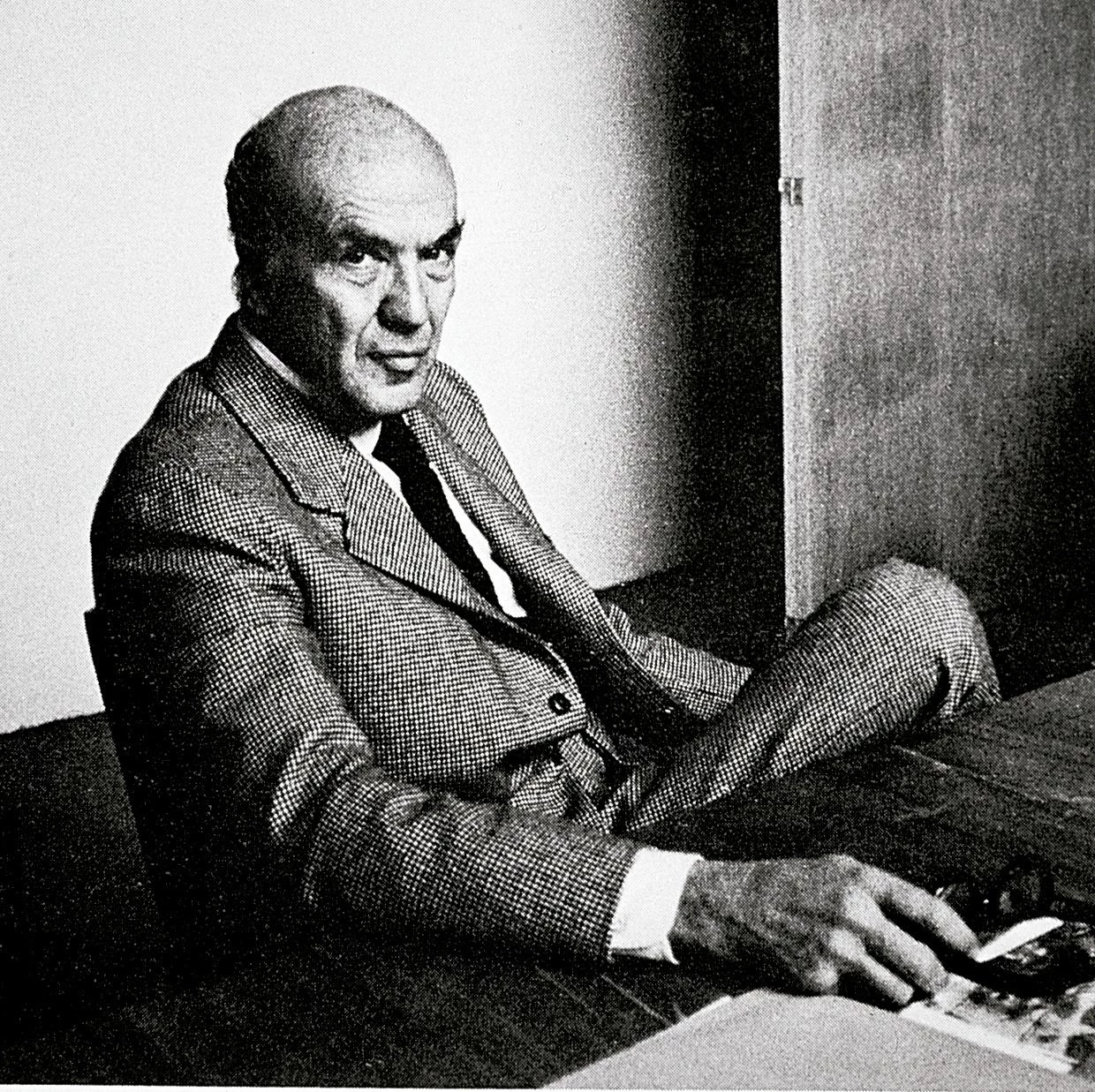

Marcel Breuer

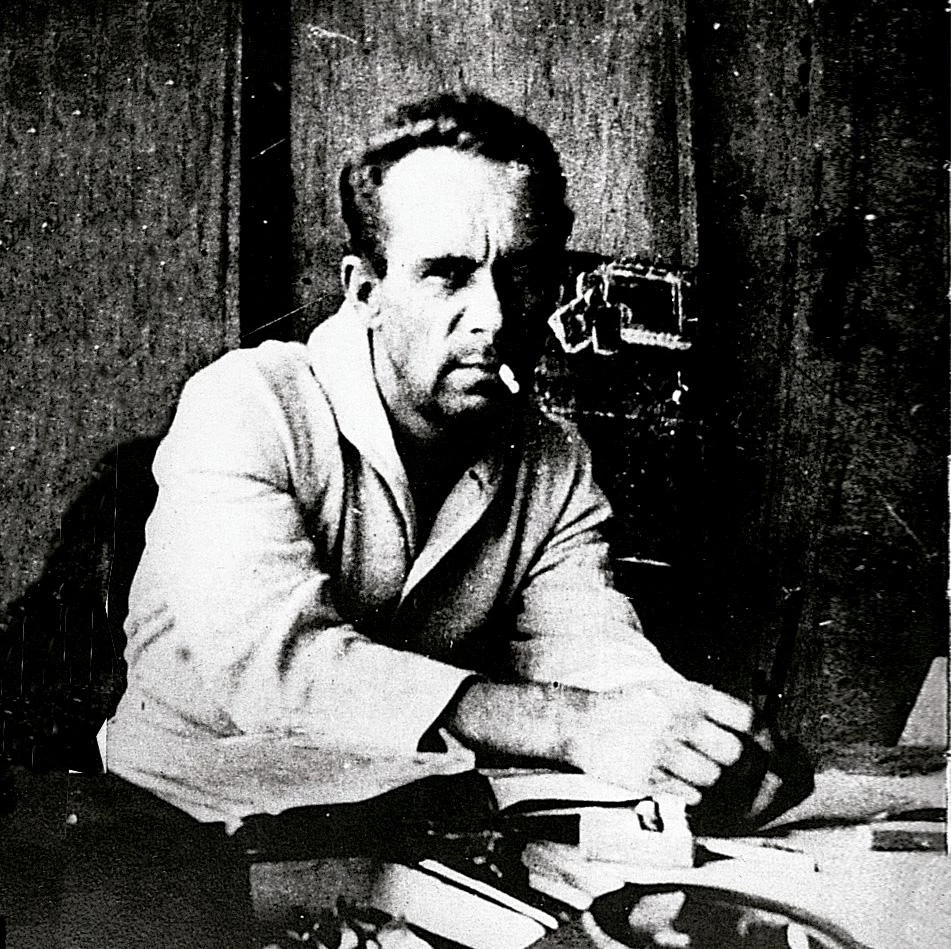

Iván Leonidov

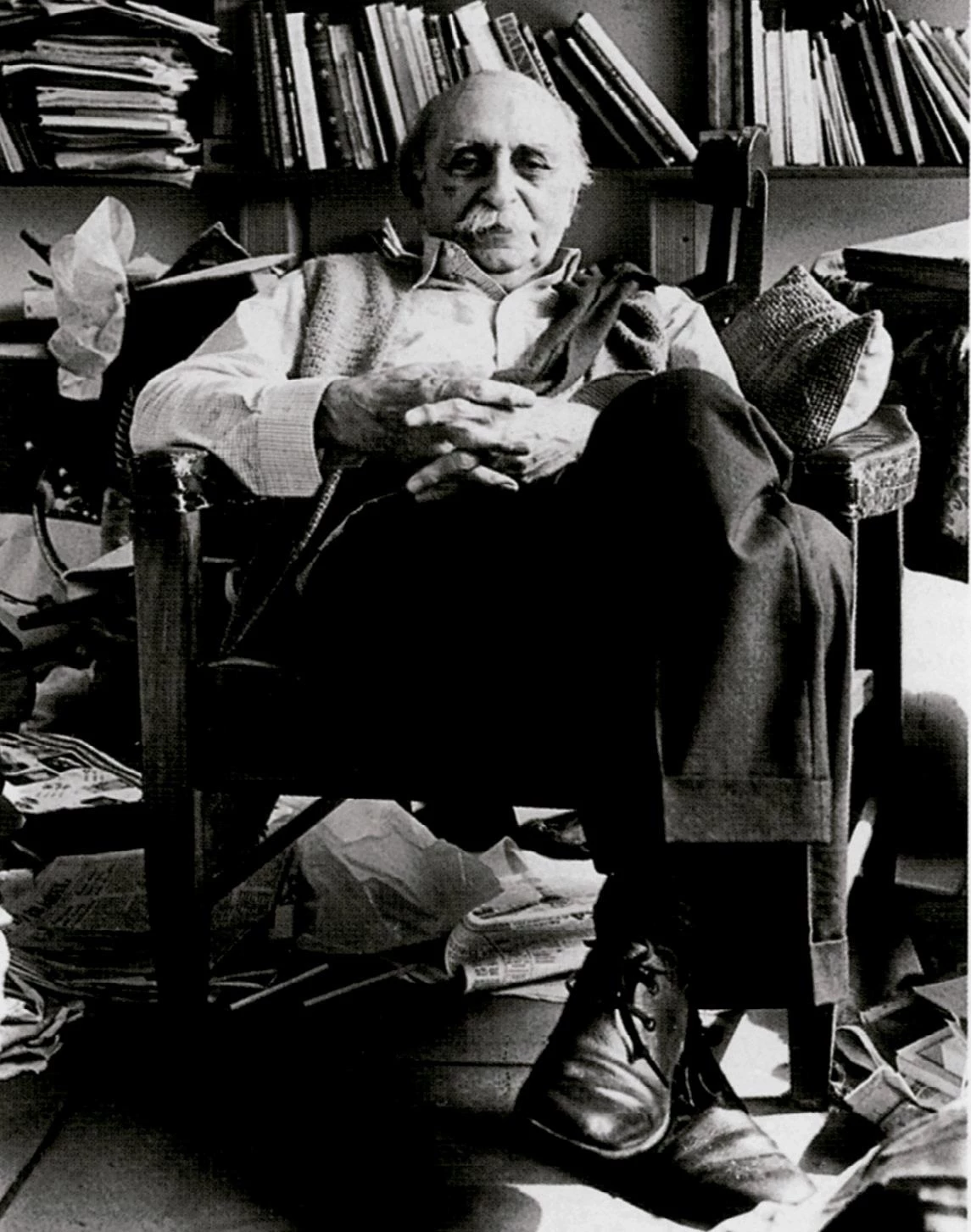

Lucio Costa

Finally, Breuer lived the modern adventure from the medullary core of the Bauhaus, which he became part of early on as a student. By the time he turned 22 he was heading the department of furniture design, and it was here that he elaborated his mythical steel tube pieces, the Wassily chair of 1926 (in honor of co-teacher Kandinsky) and the Cesca chair of 1928, both still in production. It was as an architect that the designer wanted to be recognized, however, but full acknowledgment as such did not come until the residential works of his exile in the United States, where he went fleeing from the convulsion of interbellum Europe and following the trail of Gropius. His numerous houses and occasional institutional buildings in America nevertheless suffered a loss of creative tension that cannot be attributed exclusively to the regionalist and expressive revision of those functionalist dogmas of heroic modernity that he himself had helped forge decades before.

So, did the dreamer Leonidov, the pragmatic Jacobsen, the persuasive Costa, the tranquil Barragán, and the restless Breuer all live in the same century? What is sure is that they did not live in the same chronological time as Antoni Gaudí, fifty years older, whose sesquicentennial is therefore being celebrated simultaneously. Their vital and artistic trajectories trace a multi-faceted and blurred portrait of the 20th century, a period in which it would be difficult to place the Catalan giant. Nevertheless there are authors, such as Charles Jencks, who insist on locating Gaudí at the heart of the recently finished century, who consider not only that this is the historic time he rightfully belongs to, but also that he must be recognized – ahead of Wright, Le Corbusier, Mies, and Aalto – as that century’s best architect. Gaudilatry, previously only a Catalan, Japanese and Vatican phenomenon, now encroaches upon the English-speaking world. After the 14 exhibitions of 2002, the Gaudí cult will have spread throughout the planet.