Signature Skyscrapers

New York and London add to their profile signature architectures, while Chicago, Shanghai and Hong Kong compete for the height record.

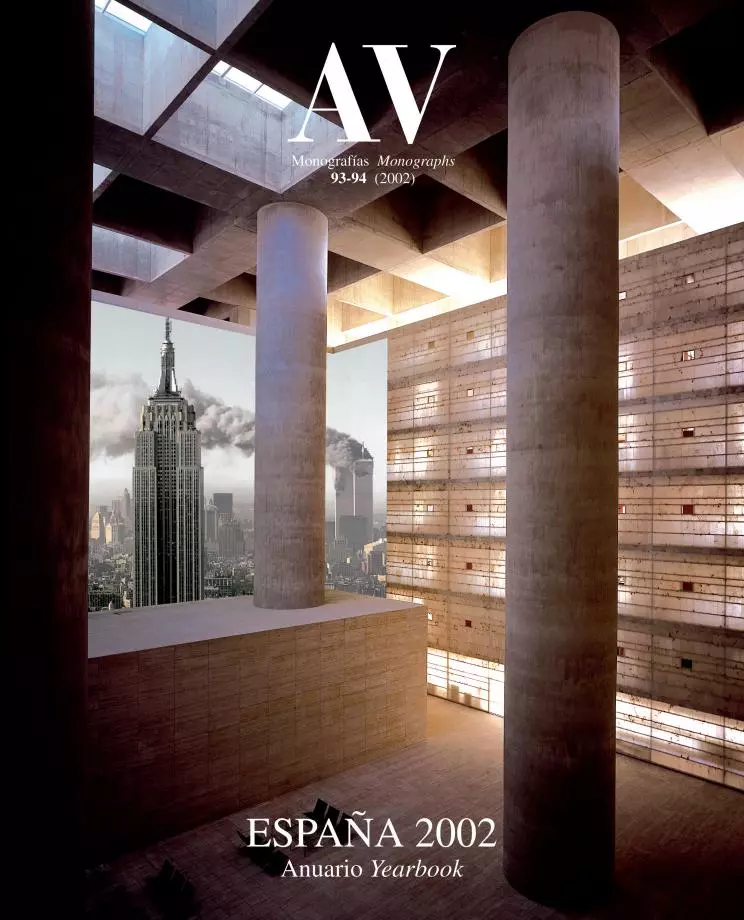

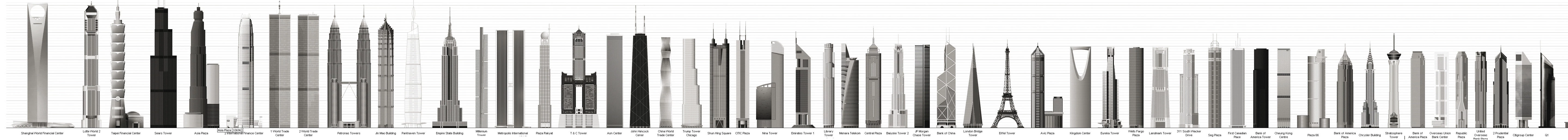

Skyscrapers grow with stockmarkets, their height marks reproducing the profile of stock prices. According to The Economist, financial soothsayers predict the future by counting cranes and every prolonged period of stock exchange euphoria leaves a building record as a testimony. The long boom of 1895-1906 ended at the same time that the Singer building was finished; that of the rolling twenties reached its catastrophic denouement of 1929 in simultaneity with the completion of the Chrysler’s and the Empire State Building’s crowns; and that of the fifties and sixties terminated shortly before the inauguration of NewYork’s World Trade Center and Chicago’s Sears Tower. When in 1996 Kuala Lumpur’s Petronas Towers beat the height record that the latter had held for more than two decades, some interpreted the feat as an indication of the exhaustion of the financial fever that had made skyscrapers proliferate on Asia’s Pacific rim, and the subsequent bursting of Asia’s economic bubble served to validate such forecasts. At the start of 2001, the slowdown of stockmarkets throws shadows on many of the projects that threaten Malaysia’s height record, although it does not seem to hinder the culmination of the signature skyscrapers now going up in New York and London.

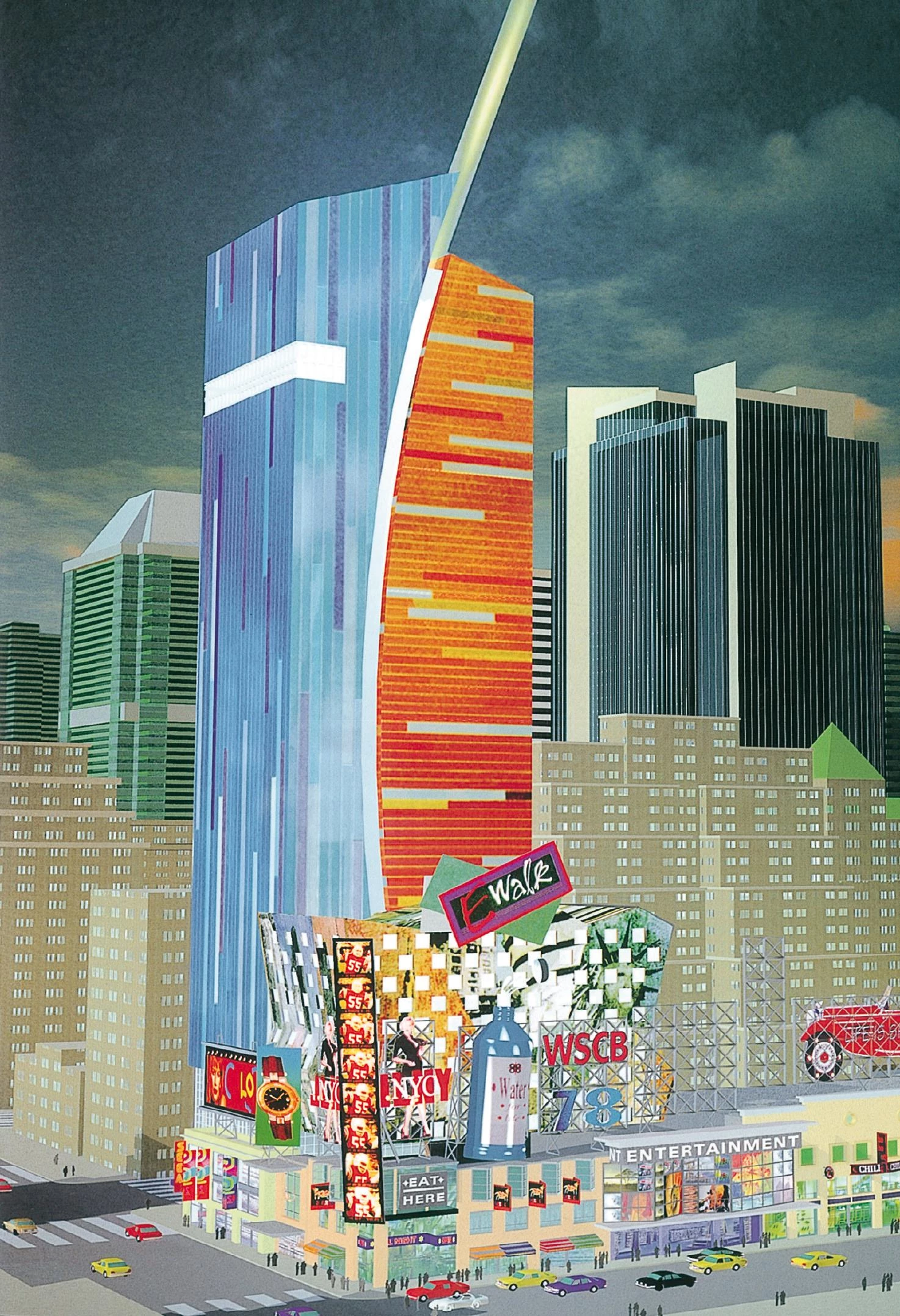

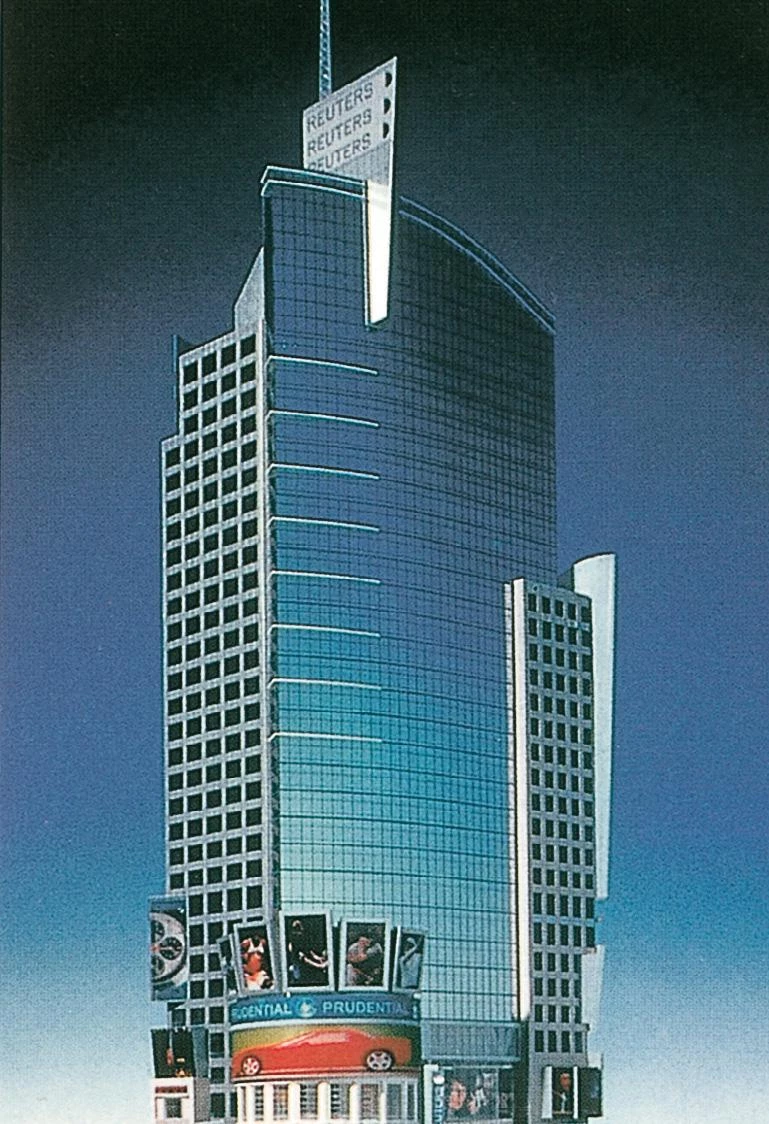

The recent skyscrapers in New York, at the service of the media industry, capriciously fracture their volumes and facades.

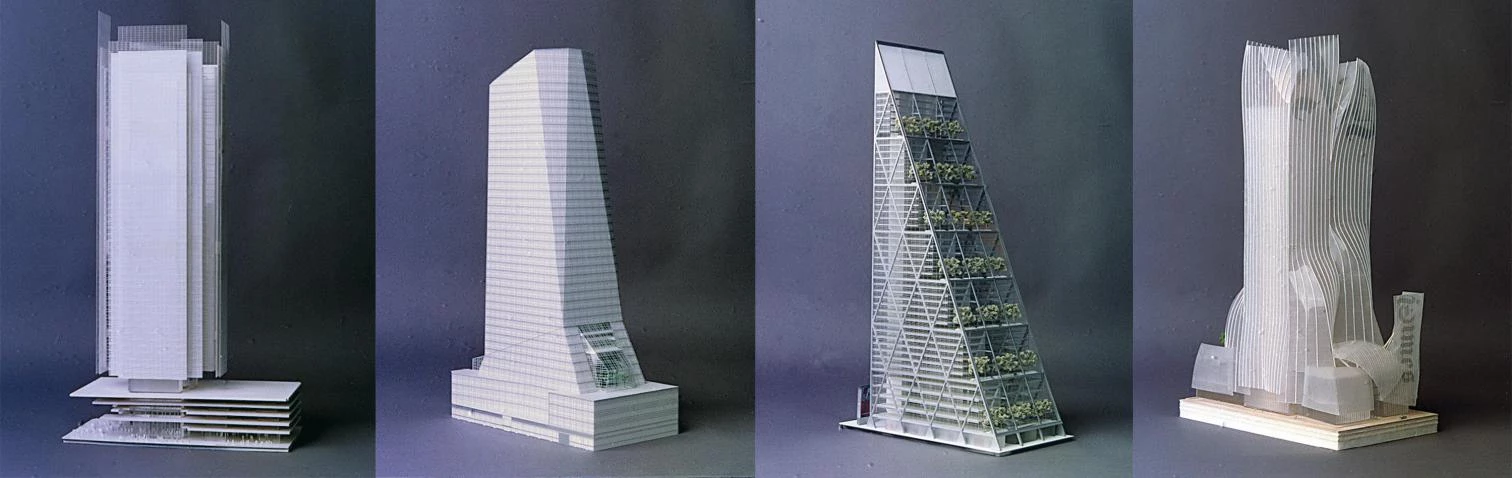

The present period of exceptional prosperity and growth in the United States has given new life to an architectural typology almost deemed obsolete, the skyscraper, altering its form and function. Unlike the categorical masses of past office buildings, the new towers have fractured volumes and hazy facades so as to fit in a heteroclite agglomeration of commercial, administrative, and residential uses. A good example of this process of picturesque fragmentation at the service of the media industry is the new constructions on Times Square and 42nd Street. These are the project for the Westin Hotel, by Arquitectonica, the skyscraper for Condé Nast and Reuters, by Fox & Fowle, and the very latest addition to the neon heart of the Big Apple, the new headquarters of The NewYork Times, the mythical newspaper that gave the Manhattan square its name when it first moved there in 1905, and that a century later hopes to inaugurate on the site a tower designed by Renzo Piano, in collaboration with Fox & Fowle, which recently won in a competition over projects by Norman Foster, Cesar Pelli, and Frank Gehry with David Childs of SOM.

Like other highrises on Times Square, the newspaper headquarters will be a modest skyscraper rising 45 floors and 200 meters, more than any Spanish building but less than half the height of the WTC Twin Towers just a few blocks downtown. Its uniqueness comes not from its scale, but from the developer and the architect involved. The 1922 competition for the headquarters of the Chicago Tribune was a milestone in architectural reflection on sky-scrapers, and one inevitably reckons that the owners of The NewYork Times had this illustrious precedent in mind when they subjected the design of their new building to competition. Surely they also knew that the judgment would be carried out with the bar of excellence that naturally imposes itself when it is a news paper at stake. The selection of Piano, however, could prove to be as disappointing as that of Raymond Hood for the Chicago Tribune, with that pragmatic neoGothic expressionism which the American architect would make even more populist in later New York buildings for McGraw-Hill and the Daily News, bound to defraud the European avant-garde..

Londres es uno de los escenarios europeos donde el rascacielos ha adquirido una nueva vigencia, a veces no exenta de polémica: la actitud ante los últimos proyectos oscila entre el entusiasmo y el recelo.

With its double glass skin and ceramic latticework, affectedly raised on a five-story plinth containing commercial and public uses, the tower designed by the Italian aspires to an immaterial lightness that is hard to reconcile with its blunt proportions, which address considerations of real estate profitability more than any architectural sensibility. For Herbert Muschamp, architectural critic of The New York Times itself, Piano has an opportunity to “design New York’s most important corporate skyscraper since Saarinen’s CBS in 1965,” and though he does not hide his admiration of Gehry’s proposal, finally withdrawn from the competition, he thinks that the Genovese “will give us something more refined and subtle” than the Californian’s project. It is not easy to share his ingenuous enthusiasm, less nuanced than the ironic skepticism of his colleague Paul Goldberger, who in commenting for The New Yorker the new building of Condé Nast, publisher of said magazine, limits himself to evidencing the extinction of the iconic skyscraper in favor of confused or diffused towers.

That in fact is what the new skyscrapers of Times Square are, whether the KPF on number 5, with its disconcerting diagonal fracture on the facade and its catalog of glass panes, or those by Fox & Fowle on number 4 (Condé Nast), with its five kinds of cladding ranging from the granite front dotted with windows to the curtain wall, and number 3, where Bruce Fowle boasts having used six facade types to come up with a different image from every angle. The latter collaborates with Piano in The New York Times building a block away, and if we are to judge from the Italian’s recently completed skyscrapers in Berlin and Sydney, it seems safe to think that the relationship will be a fluid one. In the competition, Gehry proposed his characteristic swelling organic forms in conjunction with another firm busy working elsewhere in the vicinity (SOM has designed the Times Square Tower and the building rising over the PortAuthority BusTerminal not far away), and Pelli drew up a thick faceted obelisk whose stylistic aggiornamento leaves no doubt about the technical and real estate solvency of an architect who, besides the Petronas Towers, is the author of numerous skyscrapers right in New York City.

The British Norman Foster, undoubtedly one of the most experienced architects in the design of skyscrapers, has shown an interest in his last proposals towards making them more climatically efficient.

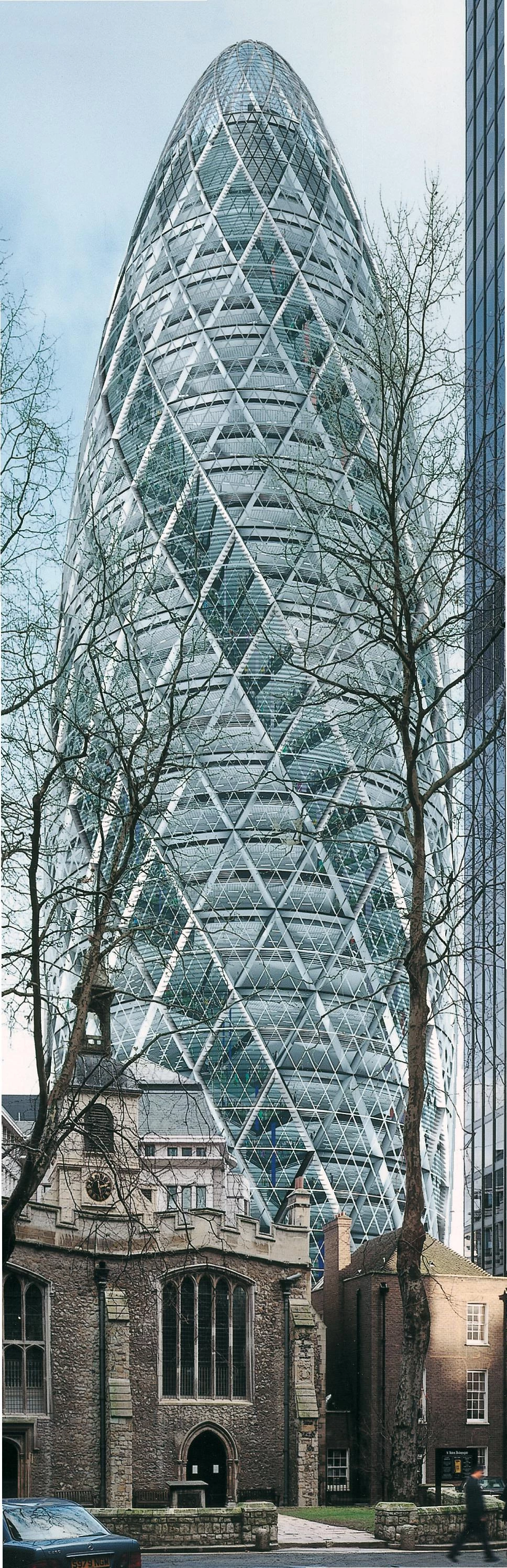

Foster was the only participant with no previous New York experience, and perhaps this explains the rejection of his project, deemed inflexible in its exact geometry, wasteful of valuable square meters in the seven-story garden-greenhouses constituting the hypotenuse of a right triangle, and tight in the top floors of its slender crown. However, this impeccable mathematical wedge was the entry that most eloquently expressed the exactitude and rigor that a great newspaper likes to be known for, and it would have gone up amidst the ruckus of that zone of Manhattan as an at once archaic and futuristic object of Pythagorean perfection and beauty that refuses to succumb to the amiable populism of picturesque exfoliation. But Foster has experienced rejection of his precision architecture even in his own city, London, where the same mayor who opposes the geodesic bubble of his town hall project, disdainfully comparing it to a car’s headlight, enthusiastically hails Piano’s fractured needle for what will, at 390 meters, be Europe’s tallest building, the London Bridge Tower. Foster previously had lost the chance to give London that record, after the discarding of his tower in the City, on the site of which he now proposes an exquisite glass gherkin rising only 180 meters, still waiting for the green light.

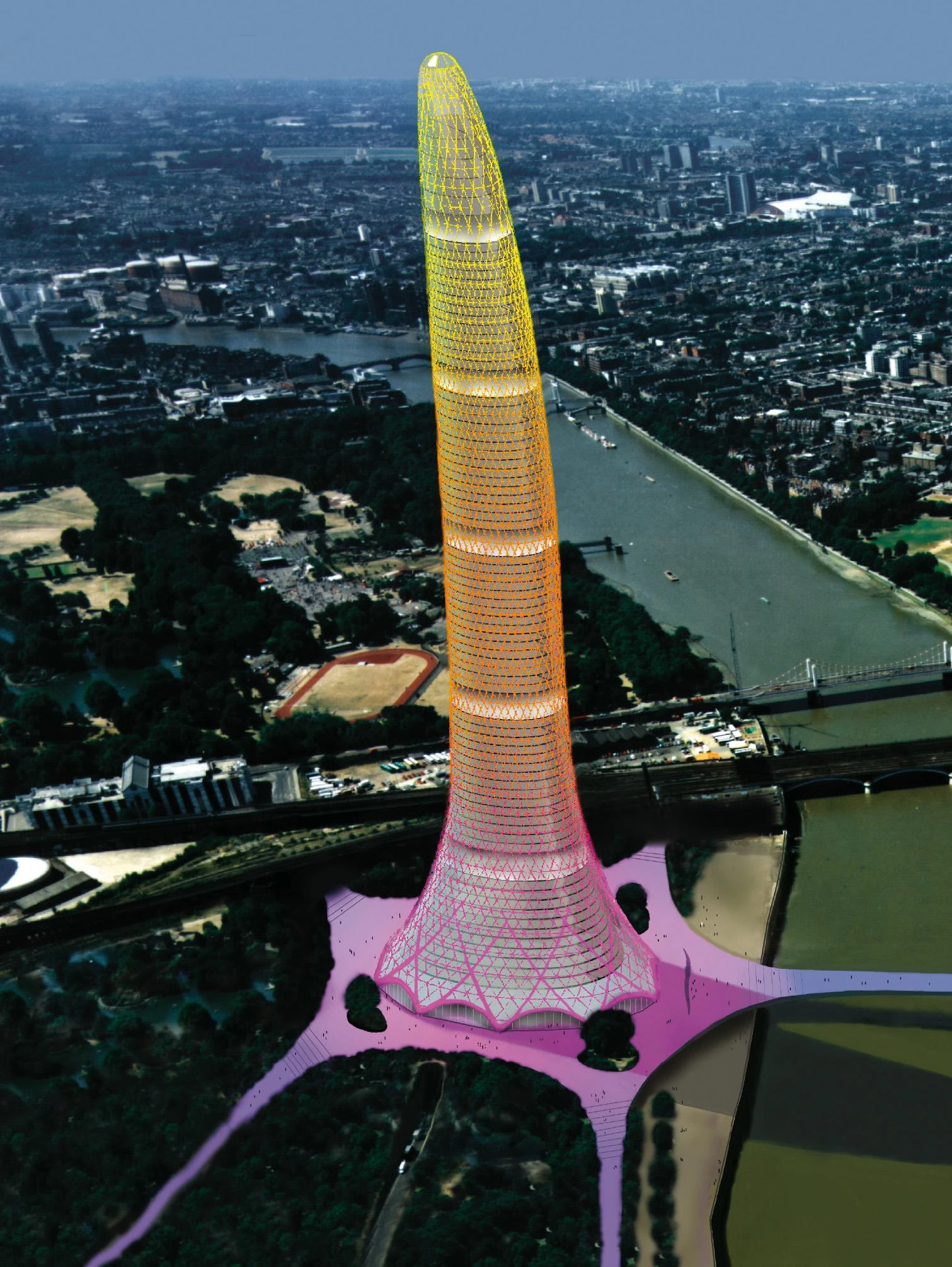

As in New York, Piano in London is working with an architectural firm of marked commercial character, in this case Broadway Maylan, authors of the first project for the London Bridge Tower. Because of the red tape in obtaining permission to build a skycraper, the de veloper decided to resort to a prestigious architect, and there is no doubt that the Italian’s charm has worked miracles. He has even gotten the mayor, the abrupt Ken Livingstone, to declare that he “will not forgive” the developer Irvine Sellar if the building does not get materialized. Such declaration of support is highly significant in a city that has traditionally been hostile to skyscrapers, although its incandescent economic situation is being manifested through ten or so tower projects, among which at least two (both by disciples of Foster) endeavor to beat, albeit slightly, the world’s current record: the Greenbird by Future Systems and the Citygate of Studio m3, two ideas brewing on paper. Not so in the case of their mentor, who has pragmatically replaced the battle of trademarks with the pursuance of innovation in his extraordinary 40-story oval tower project for the insurance company Swiss Re, that beneath the cute nickname “gherkin” conceals a rigorous proposal of singular geometric exactitude, environmental sensibility and esthetic seduction.

In any case, the race for records has more plausible scenes than London, and perhaps no more obvious one than New York, which in 1974 lost a scepter it had firmly held since the end of the 19th century. The developer Donald Trump, who like Joseph Rykwert surely knows that the height contest is the only competition that really interests New Yorkers, tried to re-gain the record for the city in 1996 with a 150-floor, 546-meter tower designed by KPF for the Stock Exchange, but the project failed, and the controversial millionaire has had to settle for the world’s tallest residential building, the Trump World Tower, an apartment construction soaring 90 floors and 262 meters whose slender minimalist prism of dark glass already rises over the United Nations building, despite secretary-general Kofi Annan’s attempts to stop such neighborly nuisance.

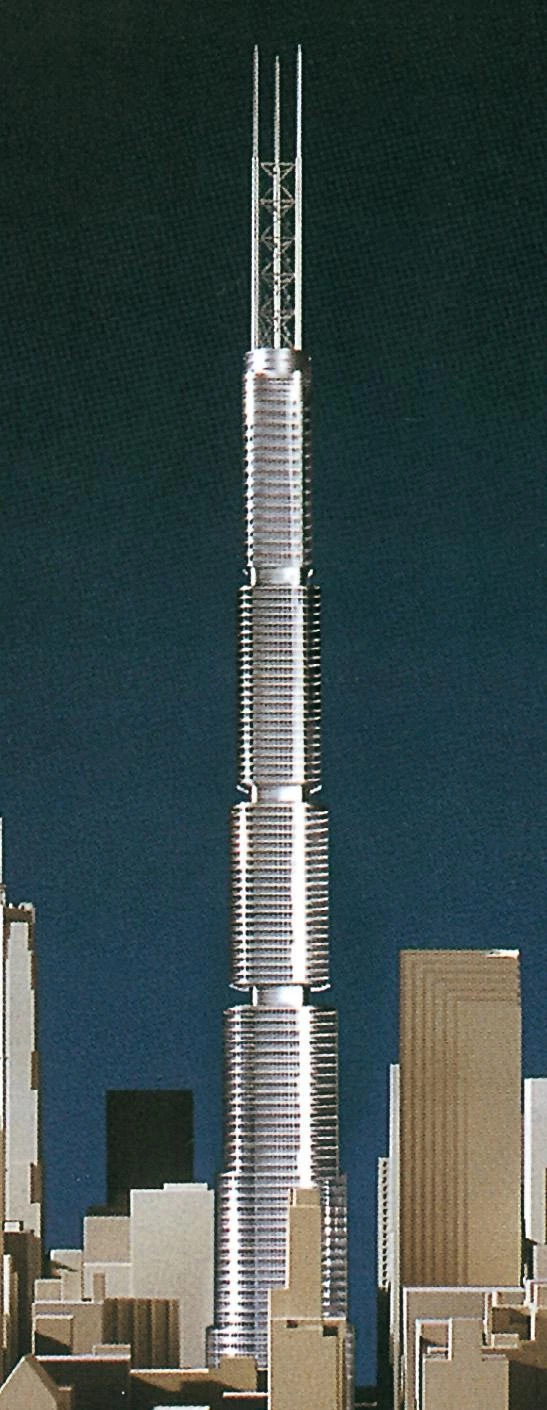

The other American city that has boasted the title of location of world’s tallest building, for 22 years to boot, is Chicago, and there, too, the spirit of revenge is cultivated, aggravated in this case by the belief that Kuala Lumpur achieved the record by dubious means (the Petronas Towers managed to get the antennae measured as an integral part of the design, the truth being that the topmost inhabitable levels of the Malaysian twins are 45 meters below those of their counterparts in Chicago’s Sears building). In the spirit of reclaiming the record for the city, the firm SOM – which thirty years ago erected the two masterworks of engineer Fazlur Khan, the John Hancock and the Sears itself – has designed on 7 South Dearborn an elegant, telescopic skyscraper rising 108 floors and 472 meters (610 counting antennae), which wouldindeed bringback the height title to the shores of Lake Michigan.

For some time now, the quest for the height record does not limit itself to New York and Chicago; the vigorous economies of Asia’s Pacific coast have also turned their cities into a fertile land to raise skyscrapers.

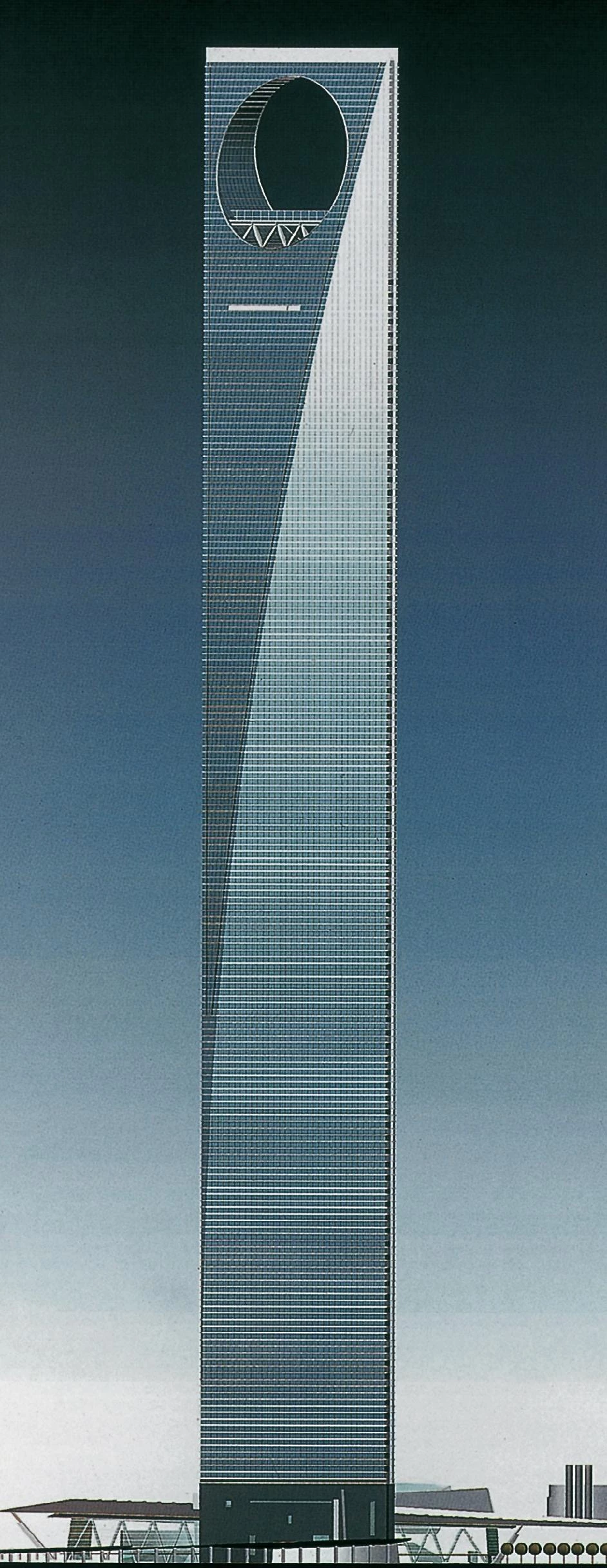

But despite the monetary and stockmarket turbulences that regularly cloud the continent, Asia continues to be both the land of promise for the more ambitious architects and the most promising destination for the most restless portfolios of capital. It is also the proposed location of Foster’s Millennium Tower, a 150-story, 840-meter colossus for Tokyo Bay still in developmental stage. It is where SOM recently finished the Jin Mao Building, a 420 meter vertical pagoda in Shanghai, as well as the Kowloon Tower, a faceted 574-meter needle on the edge of Hong Kong’s bay that is a tribute to Frank Lloyd Wright’s visionary milehigh tower. And it is where the year 2005 will see the completion of Shanghai’s World Financial Center, the tower which KPF has designed like a cosmic bottle-opener, and whose bona fide 460 meters are to date the surest bet in ousting the clever Kuala Lumpur sisters from first place in the height contest. But we will have to remain alert to indications of the stockmarket, the convulsions of which are more devastating for skyscrapers than the worst earthquake. The profile of the city continues to be an efficient financial seismograph.