Benidorm in Positive

The inauguration in a Mediterranean city of Spain’s tallest building shows the success of a tourist development often misunderstood.

Benidorm is a hamburger: the McDonald’s of tourism, an admirable combination of quality and price that ignorant snobbery contemplates scornfully, but whose persistent success ought to in-spire more emulation than suspicion. Benidorm is also the Spanish city that boasts the largest number of skyscrapers, a colossal accumulation of towers that the traveler discovers after a curve in the high-way, set amid scorched hills, like a hallucination sparked by fatigue or a mirage in the hot desert. And, above all, Benidorm is an extraordinary so-cial experiment, an economic and mass media invention built in less than half a century by an urban planning enterprise that has proven to be exceptionally efficient in the use of both territory and natural resources.

With an intensive model based on the maximum use of land and natural resources, Benidorm – the first Spanish city by number of skyscrapers –has been the leading tourist destination in Europe for thirty years.

In a recent interview, the American writer Philip Roth reproached Europeans for their hostility to McDonald’s, after all a clean, bright and cheap eatery that welcomes poor people, senior citizens and loners, thereby performing a laudable social function. And the Navarrese sociologist Mario Gaviria has for three decades been trying to make Spaniards see that the hamburger tourism of charter flights and beach is, on one hand, the materialization in the space of leisure of the social contract of the European welfare state, and on the other, a complex industry our country has won leadership in. Gaviria tells how his book La séptima potencia (The Seventh Power) was entitled “España en positivo” (Spain in Positive) before the socialist party appropriated it as a slogan in the campaign for the legislative elections of 1996, and the title of this article is a gesture of recognition for our most unbiased pioneer of tourism analysis.

For his disciple José Miguel Iribas, a Basque sociologist who has become the leading defender of the intensive model of tourism, “Benidorm’s success cannot be explained without referring to the power that its urban condition gives it.” Against the extensive tourism of landscaped residential devel-opments that eat up huge stretches of soil and water, Benidorm’s density enables it to take in five million tourists yearly along only seven kilometers of coast, and exchange the irreversible sale of quality space for the dynamic management of it through hotels and apartments of quick turnover, as Iribas reasons in the article he contributes to the book-project Costa Ibérica (a hyperbolic Utopia in images, elaborated by the Dutch team MVRDV, that advocates the exacerbation of the intensive model). If the in-erruption of monotony by vacation season plays the anthropological role of bygone agrarian festi-als, the contemporary industrial organization of the fiesta requires the economies of scale and the complexity of the urban domain: the best theme park is the city itself.

On one end of Poniente beach, and undertaken by a local developer, rises the new symbol of the urban muscle of this Mediterranean site: with its 52 floors, the Gran Hotel Bali holds the Spanish height record.

Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown showed architects the loud lure of Las Vegas; the ‘new urbanists’, led by Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberg, extracted lessons from the mass seduction of Disneyland; and Rem Koolhaas discovered the violent energy of congestion in the new cities of Asia’s Pacific coast. Benidorm, in fact, amalgamates the vulgar pleasures of Las Vegas, the pedestrian logic of Disneyland, and the implacable efficiency of the Asian urbs in a Mediterranean synthesis that attracts Brits and Dutch, Madrileños and Basques alike: a tourist city that has for thirty years and without competition topped European rankings for number of visitors, whose stubborn growth never seems to wane, even in times of crises like the cur-rent one, and which through an intelligent mix of offers has managed to transcend the seasonality of demand, that Achilles’heel that devastates the economic rationality and the urban plausibility of so many summer resorts.

The 17 May opening in Benidorm of Spain’s tallest building and Europe’s tallest hotel is not an anecdotal circumstance, but a true expression of both the entrepreneurial muscle of a region and the vigorous success of a tourist formula. Inaugurated by an ex-mayor of the city, Eduardo Zaplana, then president of the Generalitat Valenciana and now a minister, the Gran Hotel Bali is an entirely au-tochthonous product: built in the course of 14 years with no credits or external financial support by Joaquín Pérez Crespo, an Alicantine quantity sur-veyor turned real estate developer and hotel entrepreneur; designed in the architectural studios of the Valencian Antonio Escario and the Benidorm part-ners Sanchis & Luelmo; and calculated by the Alicante engineering office of Florentino Regalado, a civil engineer who specializes in concrete structures and can boast having carried out over a hundred buildings over twenty stories tall, among which Spain’s most slender construction, the Soinsa tower, also in Benidorm.

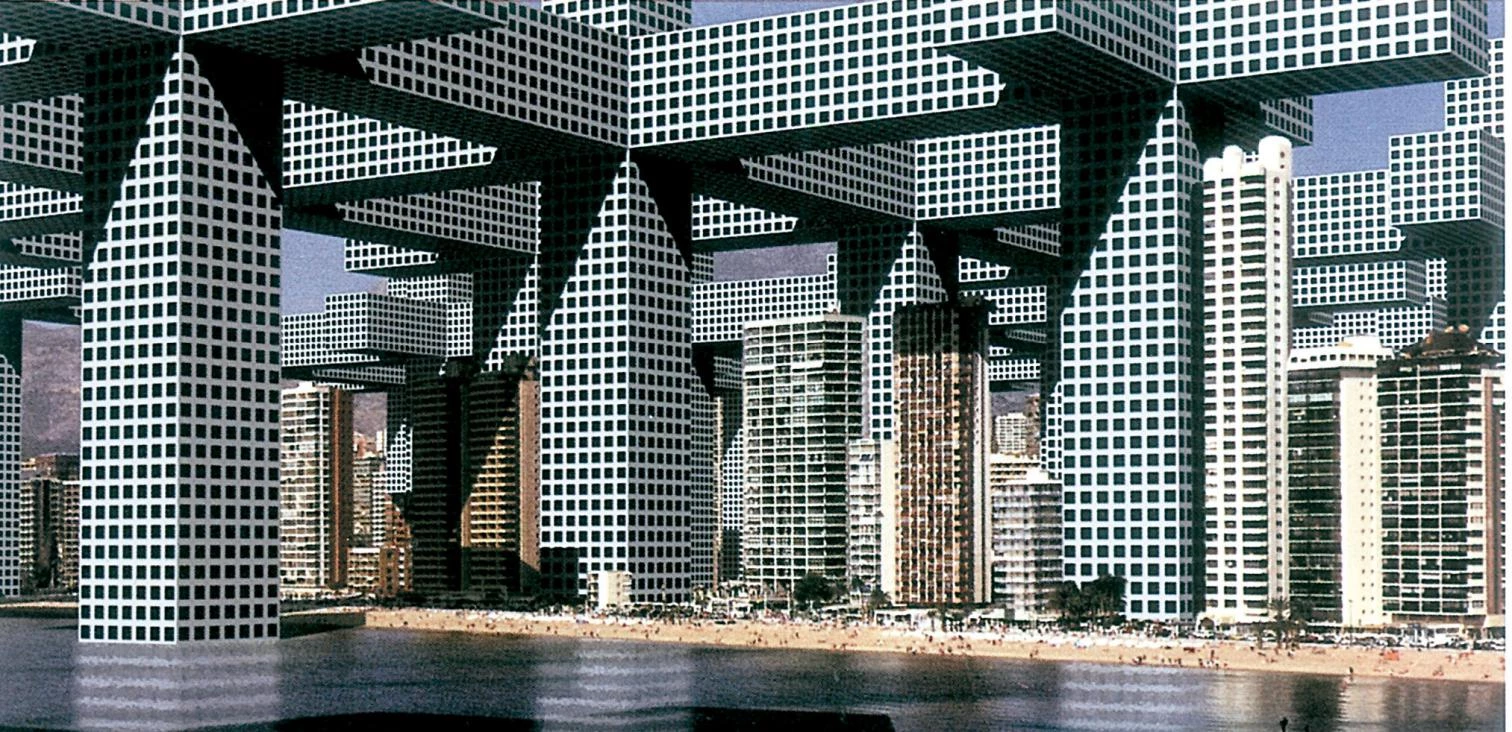

The team MVRDV used Benidorm as paradigm in their Costa Ibérica, a proposal of high-density, high-rise developments (above and below) to replace the present occupation of Spanish beaches with scattered constructions.

In the final analysis, the tapered, candidly Gothic bulk of the Bali can only be conceived in the en-ergetic context of a unique city: the 52 stories and 186 meters (210 once the mast is installed) far ex-ceed the 157 of Madrid’s Picasso Tower or the 154 of Barcelona’s Olympic Village highrises, but this is surprising only when we forget that of the 200 Spanish buildings over 75 meters tall, 132 are in Benidorm, against the 43 in Madrid and 18 in Barcelona. In the same way, the Bali’s 1,608 beds may seem formidable, but not so much when we remember that without them Benidorm already has more hotel rooms than Madrid, surpassed in Eu-rope only by Paris and London. And its incredibly long execution time, caused by the resistance of the developer to resort to loans (halting periodically construction work, what allowed Bigas Luna to use the empty structure on the site for a scene of his film Huevos de oro), can only be understood in terms of its proud status as a home-grown project, one which celebrates its culmination with a plaque that explicitly mentions the absence of serious accidents in 5,000 days of construction.

From its parabolic take-off to its pyrotechnic crest of porticoes, the Bali rises at the far end of the Poniente beach with the aplomb of one who owes no one anything, the symbol of a tourist revolution which has put Spain in that exclusive club of four countries – along with the United States, France, and Italy – that top all statistics, whether number of visitors, revenue, or hotel space. Initiated during the mayoralty of Pedro Zaragoza (a daring dream-er who had an ambitious urban masterplan approved, while travelling to Madrid on a Vespa to ask Franco for tolerance toward the bikini, and prmoting Benidorm in Europe through a festival of light song and a seedy but brilliant advertising campaign), this tourist revolution is in the collective memory of Spaniards associated with the anarchic development characteristic of the sixties, and to this day it provokes hostility, incomprehension, and disdain: after the newspaper El País published on the cover of its Sunday magazine an extraordinary aerial photograph of the hundred towers cluttering Benidorm’s Levante beach (the one also used as first illustration in this article), letters from readers came storming in, lamenting that such image should represent Spain. But this vulgar and vibrant city is a colossal machine for circulating money and pleasure, a vertical version of Mediterranean urbanity, and a titanic and trivial theater of the bacchanal and banal leisure of the working Europe.