Landscapes of Passion

The new landscape design builds the environment with geometry and gesture, introducing order in the city as in the examples of Strasbourg and Baracaldo.

Europe a lust for landscape. On one hand, the continental territory suffers an ordeal of scorn and aggressions that distorts its profile, damages its integrity, and altogether jeopardizes its existence. On the other, landscaping as an instrument for regenerating and redeeming ill-treated places is on the rise. Whether pain or pleasure, the lust for landscape feeds on prosperity, which stretches its asphalt carpet on the scant space of this small Asian peninsula, while inducing inhabitants to demand vi-sual delight and agreeable environments. But the economic effervescence that voraciously devours the territory while arousing an appetite for beauty is not abbreviated in the false fiction that opposes vegetation and construction: lawn and cement are of the same artificial nature. Two recently executed projects, in Strasbourg and Baracaldo, draw atten-tion to the manufactured character of the urban landscape, exemplarily manifesting architecture’s capacity to recreate public space.

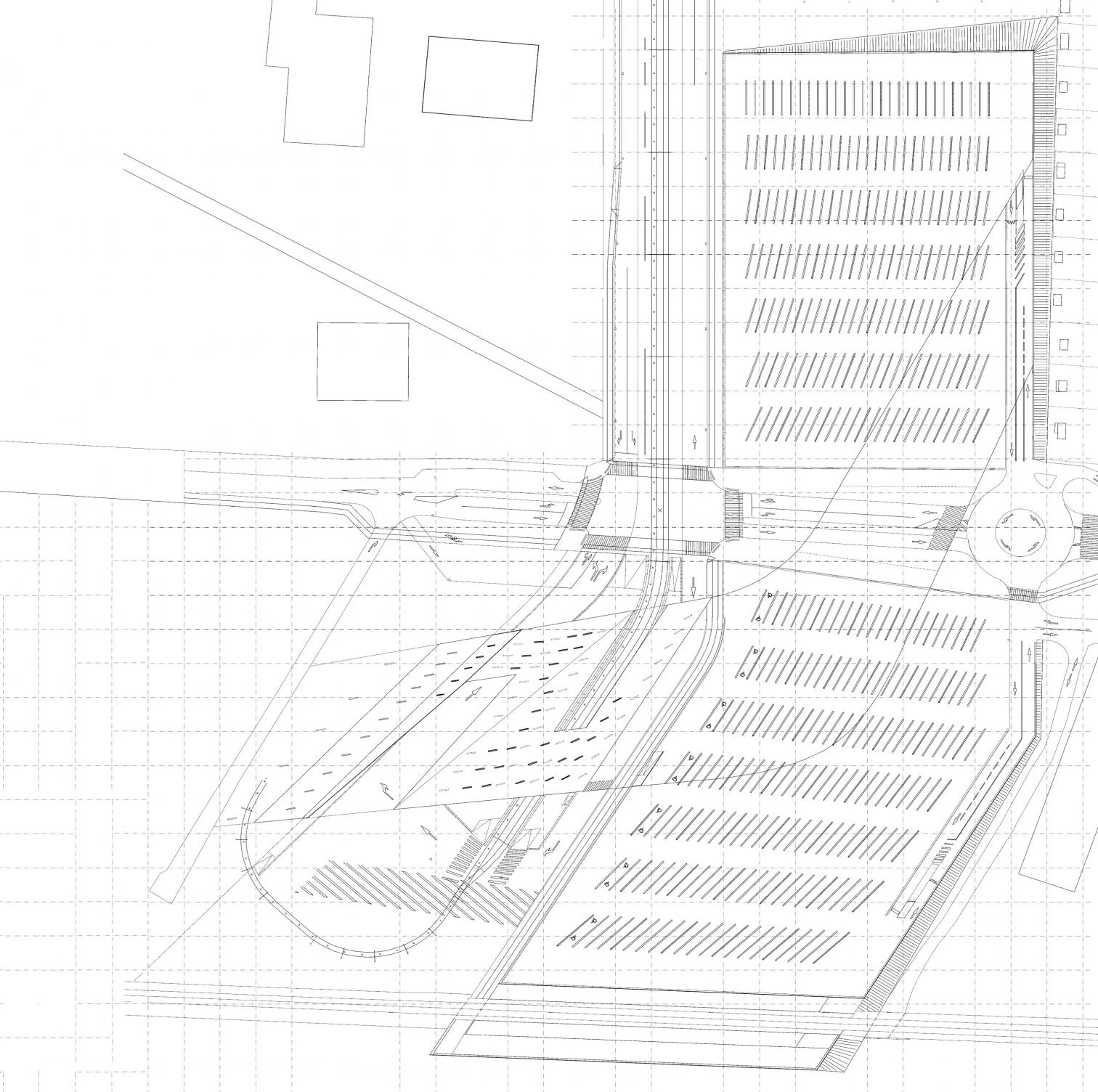

Exemplary because of the strategies used to shape the public realm, the Alsatian intermodal terminal (below) and the Basque square (left) stress the artificial character of today’s urban space.

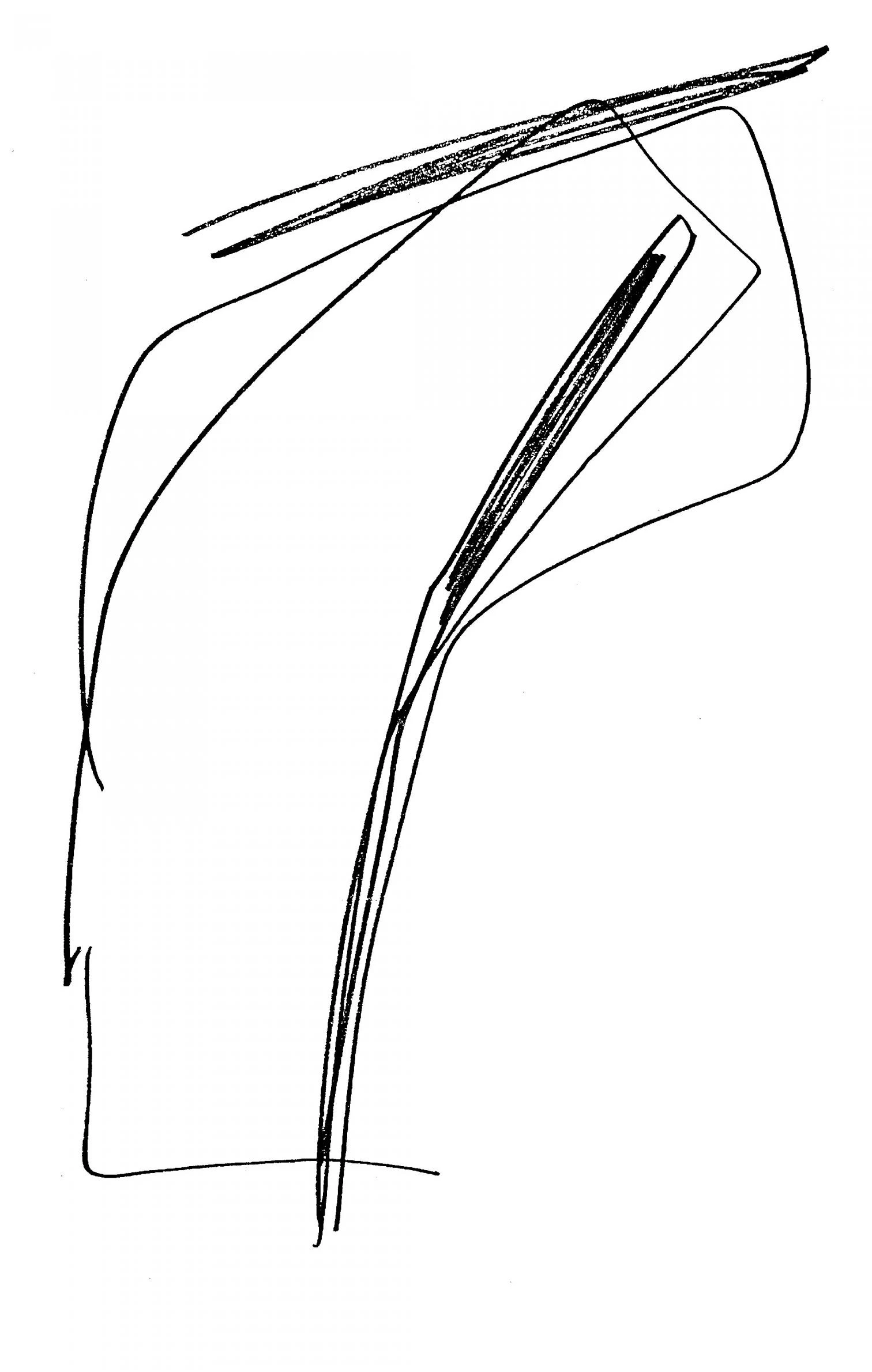

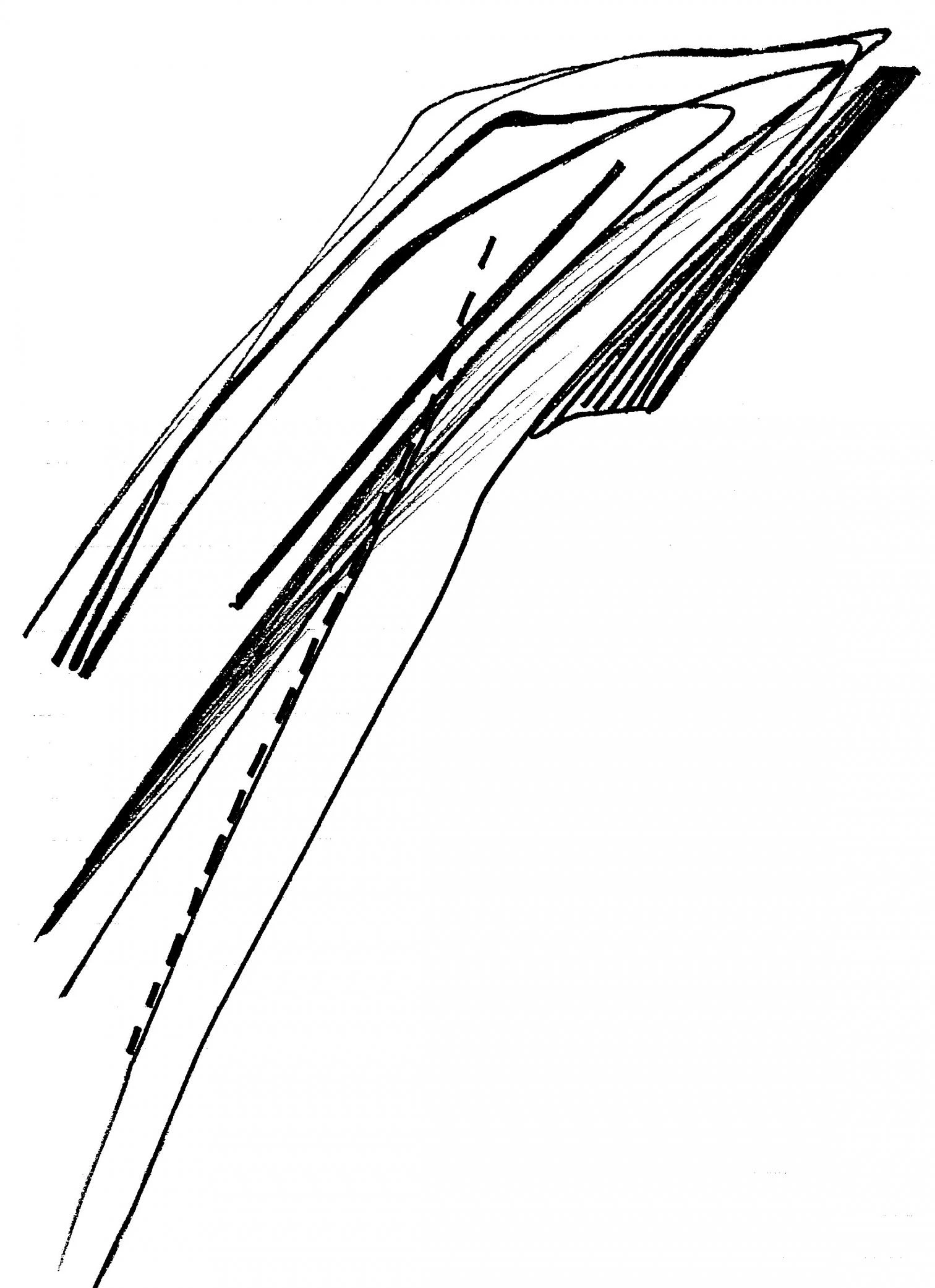

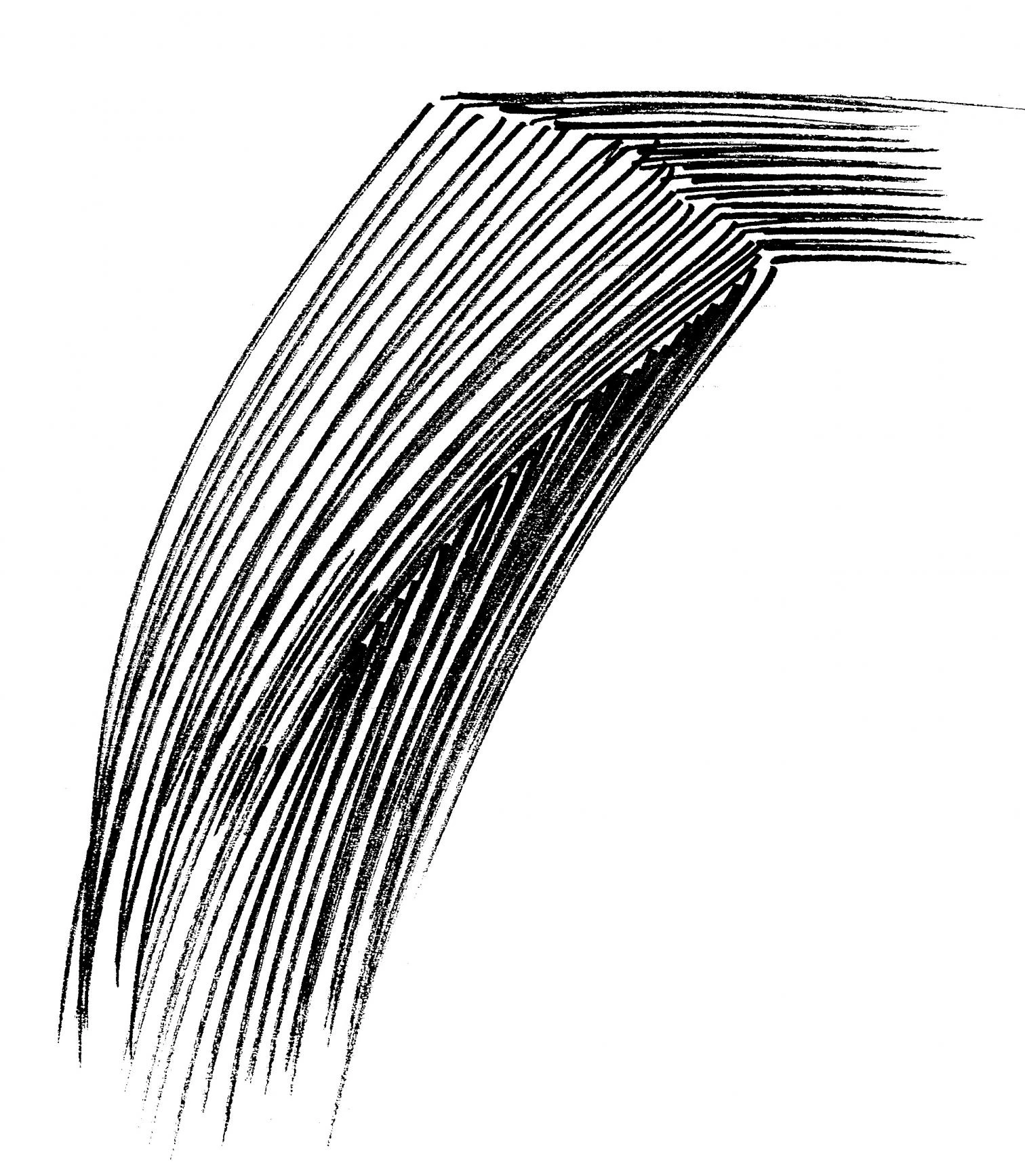

In the French city of Strasbourg, the London-based Iraqi Zaha Hadid has built an interchange –as the mixed stations of buses, trains and tramways are now called – that uses land art procedures to endow an anonymous peripheral zone with a fascinating visual identity. Justifiably proud of its futuristic streetcars, which protect the historic center from car traffic, the Alsatian city has rendered its mass transport system all the more attractive with the intervention of artists like Barbara Kruger or Mario Mertz at key points of the network. And the latest is Zaha Hadid, who has built a bus and tram terminal with a folded sheet of concrete that cuts a weightless-looking figure on the platforms while throwing a white and fleeting shadow over the parking lot, orienting users toward the station and creating a unique calligraphy of cement and asphalt where floor marks are arranged like fillings in a magnetic field, facing the sweet disorder of the place with its dynamic and abstract violence.

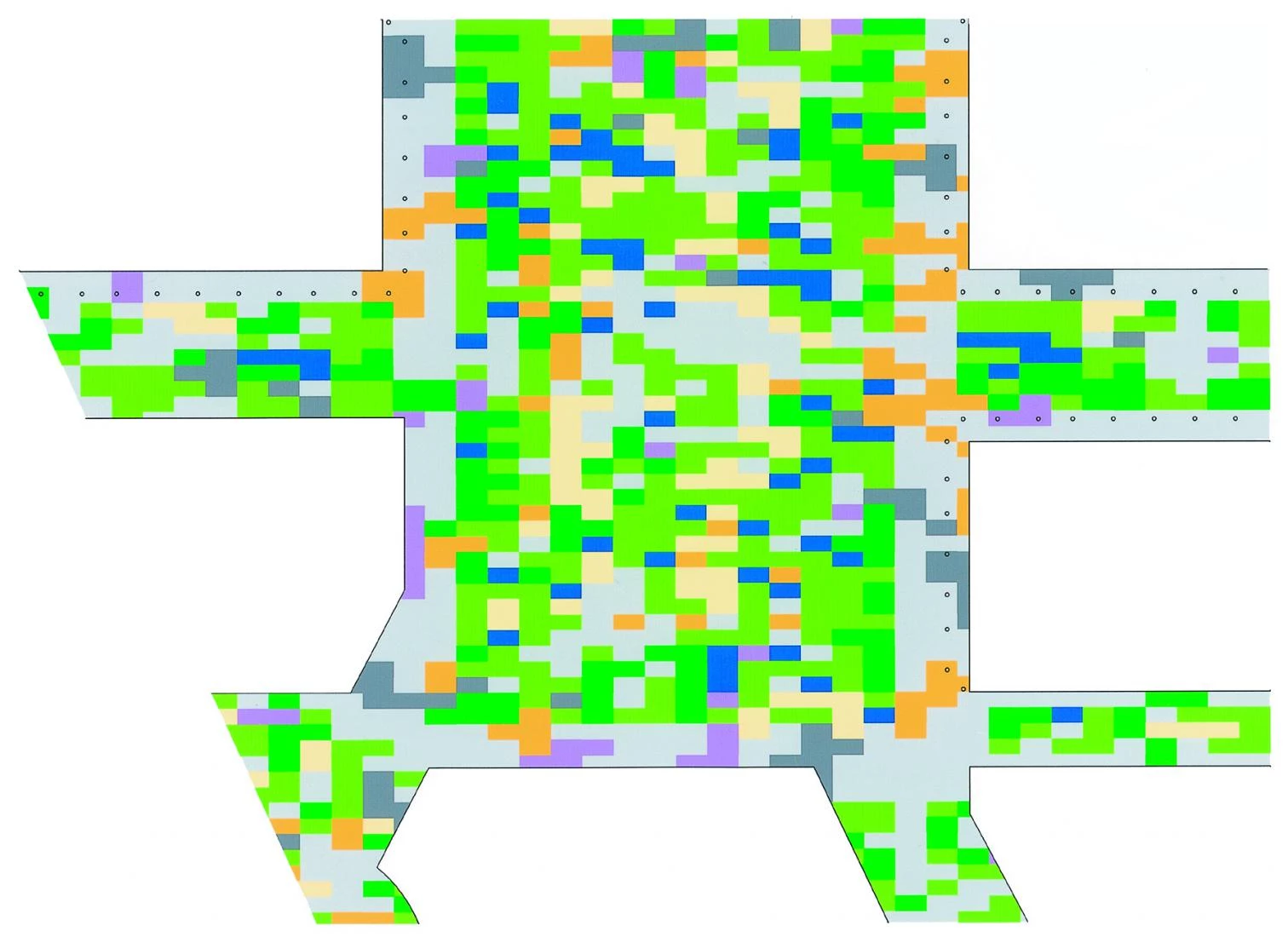

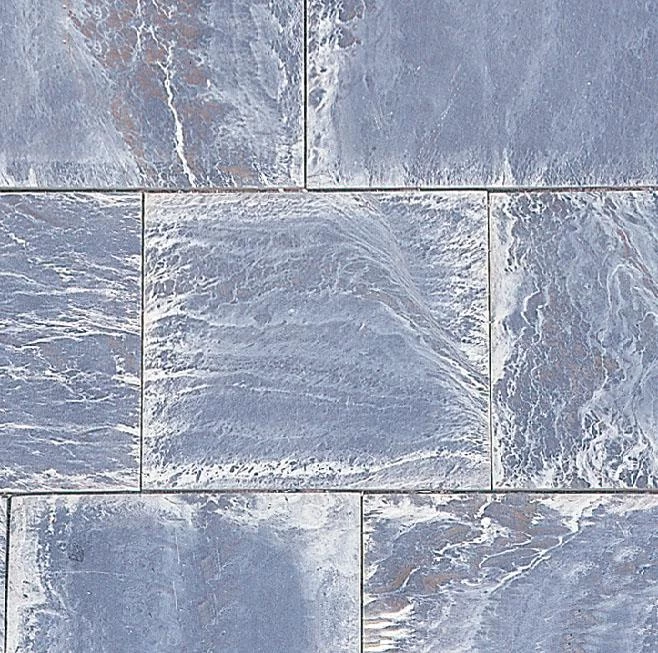

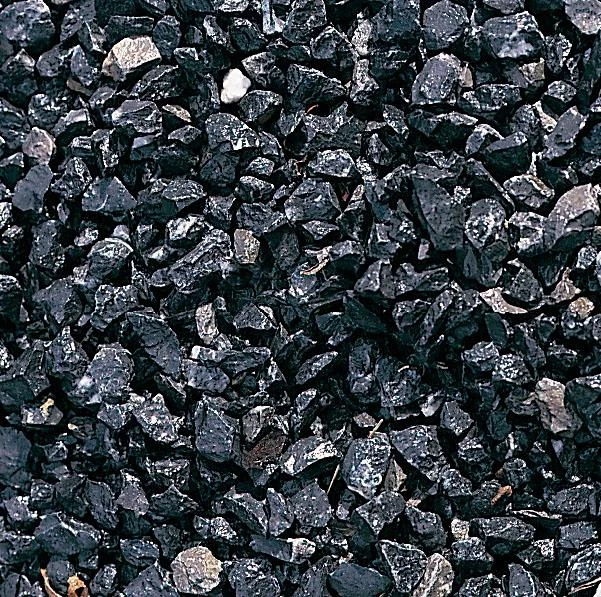

Meanwhile, in the northern Spanish city of Bara-caldo, amid residential blocks that have come to re-place old industrial plants, the Madrid-based Basque EduardoArroyo has created a square whose regular and eventful grid combines materials and uses in a playful choreography. Stretching over the railway and factory remains of this locality along Bilbao’s estuary, and framed by the sad ugliness of the sad surrounding buildings, the young architect’s plaza uses the grid to orchestrate the combination of trees, grass, and water with five materials (stone, asphalt, steel, sand, and wood) evoking the primematerials of the site’s former context. This pixelized picturesqueness, which tries to introduce both order and variety, elegantly and refinedly materializing a structuralist Dutch tradition that ranges from Aldo van Eyck’s playing fields to MVRDV’s datascapes, aleatorily colonizes a space devoid of qualities, re-deeming and rescuing its music of chance.

Exemplary because of the strategies used to shape the public realm, the Alsatian intermodal terminal (below) and the Basque square (left) stress the artificial character of today’s urban space.

Of course neither the brisk expressionism of Zaha Hadid (whose elemental graphics does not let vegetation or canopies soften the desolate expanse of the parking lot) nor the dot-matrix materiality of Eduardo Arroyo (whose combinatorial fragmentation shreds uses to the point of a labyrinthian diversity that becomes near-parodic in the warping of the ground with small bulges) is an easily gen-eralizable model. Nevertheless, both landscaping works extract their exemplarity and virtue from the intelligent way they use geometry and gesture to shape the public domain, fabricating small islands of formal discipline and visual vigor in the mediocre ocean of the generic city and blurred periphery. Alberto Caeiro, one of Pessoa’s heteronyms, warned us that “Nature is parts without a whole”, and these tatters of artificial landscape probably just have to accept their insular condition and renounce the task of reconstructing Europe’s territory with a modern order that replaces the fictitious Horatian and Arcadian totality of the classical pagus.

Though landscape degrades faster than efforts are made to regenerate it, interventions cannot be offhandedly dismissed as cosmetic acupuncture. On the contrary, these rigorous operations serve as a civic and aesthetic stimulus. Against the material and spiritual aggression of the insensitive urbanization that stretches its horizontal garbage over the territory, these landscapes are neither passive nor supine, but landscapes on their feet that clamor for a redemptive manumission of citizen urbanity. In this, Europe is true to the spirit of Enlightenment, and to the build of its common identity in the geometric crucible of reason – not the totalitarian reason that destroys Pascal’s esprit de finesse, but the dialogic reason that, through the acceptance of the reason of the other, recreates the world’s plural wealth in expressive subjectivity, and aspires to weld the cracks of a fragmented territory through hermeneutics. This may be the best tribute to the late Gadamer that these reasonable lustful landscapes could make: landscapes of penitential pain, but also of hope and happiness.

In the square of Baracaldo Eduardo Arroyo lays out a regular grid, from which he orchestrates a combination of water and vegetation with materials such as steel, stone or wood that preserve the town’s industrial past.

While Europe naps in the indulgent comfort that came to the fore in the Barcelona summit, its phys-ical future is defined on the other side of the Atlantic. Before September 11, the shift in the realm of ideas was limited to replacing Heidegger’s French children – from Foucault to Derrida – with a genuinely American way of thinking, the prag-matism that has traveled from Peirce, James, and Dewey all the way to Rorty, and this transoceanic transfer foretold that the Americanization on the rise in European territory would take the friendly, consumerist, and social-liberal form of the new urbanism, a toned down and sugary variant of the vigorous Anglo-Saxon sprawl. But in the new climate created by the feeling of insecurity that hounds the heart of the empire, the forgotten rhetoric of a totalitarianism of romantic stock has reappeared, paradoxically, in the bosom of an American republic that already twice in the past saved Europe from its familiar demons. George W. Bush uses the terms introduced by the Nazi jurist Carl Schmitt to divide the world into friends and enemies, or to replace a State founded upon the rule of Law with a State from which Law emanates. In this inverted Enlightenment, l’infâme is the Other, and it is not difficult to imagine the physical and territorial consequences, on our continent, of a process that is turning old partners into subjects. If we were to visit Heidegger’s grave, we would find the stone turned over.