Celebration of the City

Over half of the planet’s population now lives in cities, and this number, reached in 2007, demands rethinking the ecological virtues of urban density.

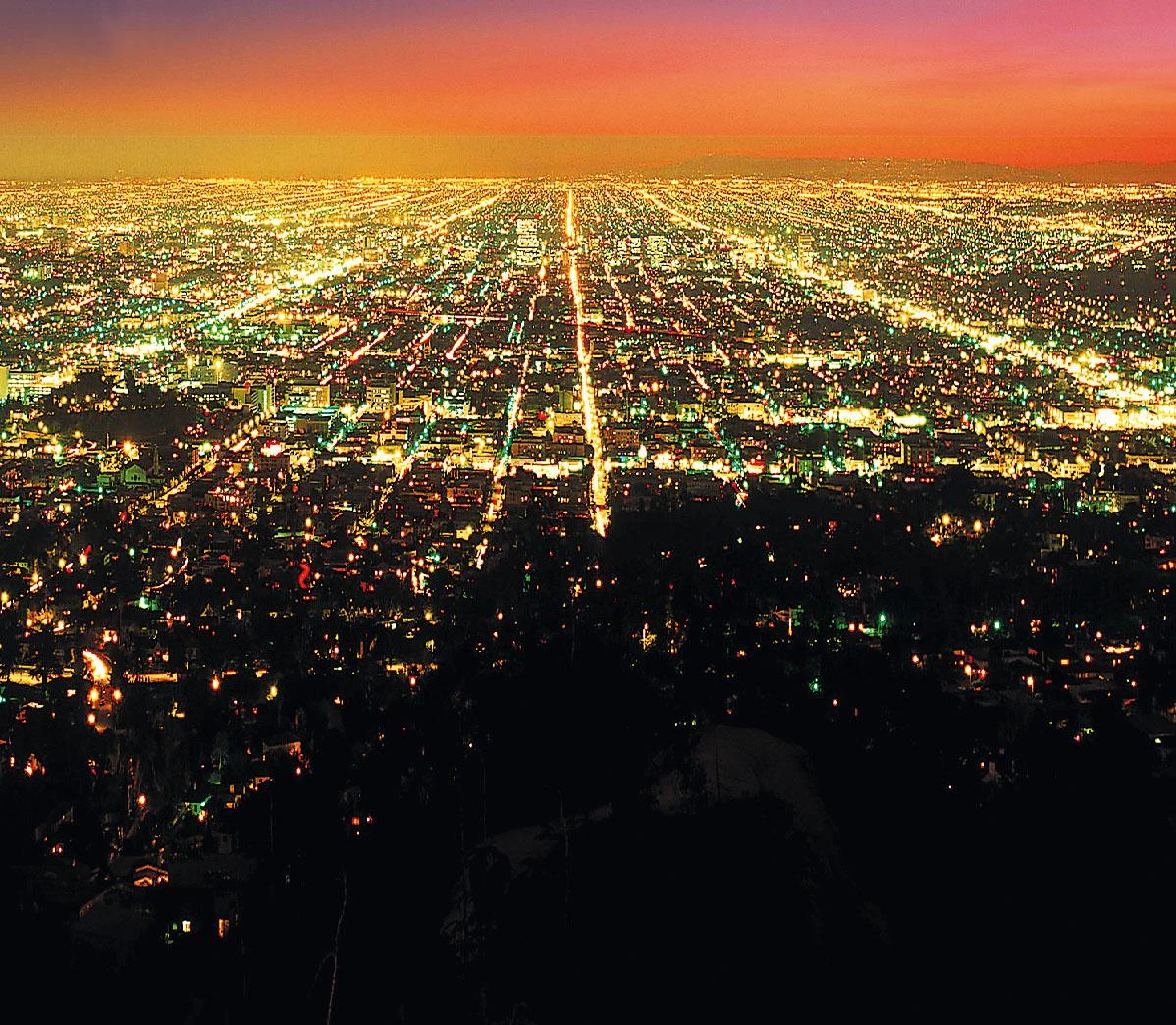

Climate is the problem, the city is the solution. This is how the spirit of the most ambitious urban program for energy efficiency launched in the United States could be summed up. Promoted by the city of Cambridge – home to universities like Harvard or MIT –, the plan starts from the premise that “many of the most difficult environmental challenges can be addressed and solved by cities”. Their defenders, Douglas Foy and Robert Healy, claim in the Herald Tribune that, much in contrast to the conventional view that associates sustain¬ability with nature, the dense city is ‘greener’ than the suburbs, because it is more efficient in its use of energy, water and land: New York City uses less energy per capita than any state in America. If the primary cause for climate change are the carbon dioxide emissions from the combustion of fossil fuels such as coal, oil or gas to produce the energy used in buildings (almost half of the total) or transport (one third), it seems reasonable to concentrate the energy-saving effort in cities, “the Saudi Arabia of energy efficiency”, abandoning the wasteful model of low-density residential areas.

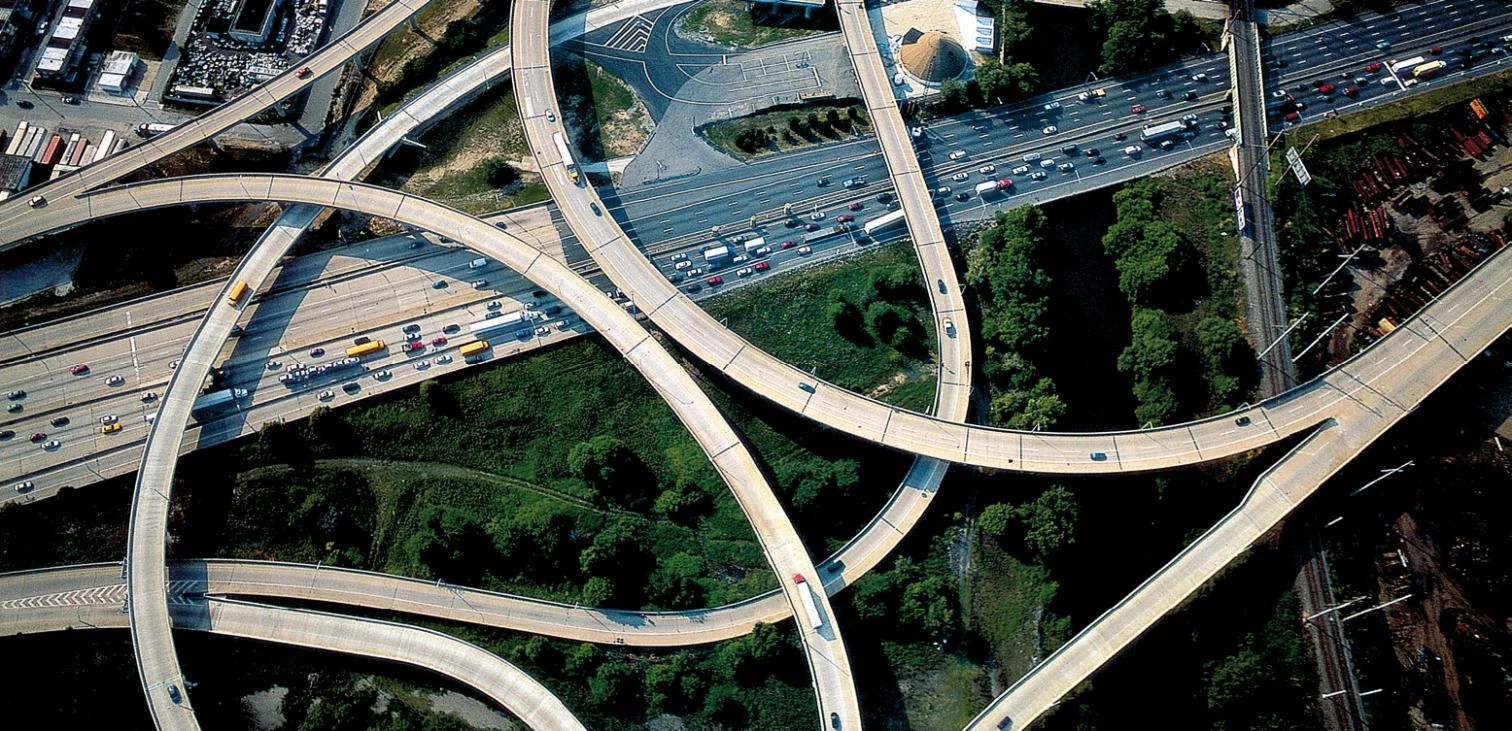

Sprawling urban growth wounds virgin land, and buries it beneath a viral spread of detached houses and entangled freeways.

After several decades of discussions on sprawl – the uncontrolled growth of a city –, Americans have rediscovered the compact Eu¬ropean city as an example of sustainability. The New Urbanists headed by Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk designed Seaside in 1979 – a residential development on Florida’s coast where the movie The Truman Show would later be filmed – to propose a greater density alternative to the scattered suburban growth that has characterized the last half century: that which is reflected in section in the itinerary of Tony Soprano while driving from Manhattan into New Jersey in the opening credits of the TV series, or that caricatured in the 45 seconds of repeated houses, repeated cars and repeated persons that introduce the chapters of Weeds. But the reform of the New Urbanists was burdened by it aesthetic traditionalism, and failed to question the arcadic nostalgia of the garden city; only now, when the measures to control sprawl have featured prominently in election campaigns, and when climate change has become a key concern of political polemic, has it become clear that the compact city is the only answer.

The American model of suburban residential development, spurred by cheap energy and plenty of land, has been adopted by the rest of the world, but cannot be sustained in a context of economic crisis and climate change.

In Spain, the combination of the real estate bubble and urban corruption has demonized cranes, density and height as sulphurous signs of evil, and politicians embrace trees with the same fervor with which they abjure asphalt, yet all of us have voted with our feet for cement. Though the gentle landing of housing prices and the rough catharsis of city scandals may assuage the ambitions of councillors and cut down the projects of developers, the alternative to the drab blocks of greedy builders cannot be the lifeless landscape of periurban, suburban or exurban semi-detached houses. The electoral offer of the Madrid region president, who proposes limiting the height of all new residential developments to three floors plus attic, is a promise as hard to keep on legal grounds as it is ludicrous to maintain on physical ones, because it would impose as single model of urban growth that which is least sustainable: a scattered city that uses vast amounts of land, water and energy, both in its construction and in the maintenance of its buildings and transportation networks; a city, therefore, that contributes negatively to global warming with an exorbitant carbon footprint; and a city, in the end, that being rhetorically green is in fact the least green of all.

As The Economist claims in a recent urban report, all happy cities resemble one another in at least two things, prosperity and good government; unhappy cities are unhappy in many different ways, but neither the decaying quarters, the corrupt administrators, the unsafe streets nor the high cost of housing have managed to deter the masses from that exodus to the urban centers which has already placed more than half of humanity in cities. These organisms grow, wither, revive or become extinguished, but they often outlive nations and empires, reinventing themselves once and again over the fertile mesh of their human capital, a more solid foundation of urban survival than the physical capital invested on its traces upon the territory. In the end, happy cities are not always the ones with a greater capacity for attraction, even if the urban rankings of liveability stubbornly privilege the almost numb calm; in the survey conducted by the British magazine, which appraises fifty world cities, the first places are occupied by the inevitable Vancouver, Melbourne, Vienna or Geneva, whereas Madrid and Barcelona both drop behind and rank 33rd, after Tokyo, Paris or Berlin, but before London or Los Angeles, which are at the tail end of the list.

The endless sprawl of the hinterlands of Madrid or Los Angeles contrasts sharply with the density of construction in Benidorm, a city of tourism whose success is based on skyscrapers.

But even the most abrasive cities attract us like a magnet attracts iron filings, and that luring power does not come from public amenities or trophy buildings, but from the material energy of their scale and the social opportunities of their diversity. The city is its people, and in the contemporary economy of knowledge the essential element of urban competitiveness is the education of its population. If density is an ecological virtue, by freeing up land and reducing energy consumption, it also becomes a social virtue by facilitating the confluence of talent and the cross-fertilization that lies at the base of innovation. Congestion, however, needs to be orchestrated so that it does not result in chaos, by means of physical traffic lights that control the flow of people or cars and legal ones that organize the circulation of ambitions or interests: these traffic lights are another name for good urban government, and if these are enhanced by the promotion of the material capital embodied in their transport, education or health infrastructures, and of the social capital that resides in mutual trust and the protection of the weak, the compact city becomes the best stage for life, the most sustainable residence on earth, and the most genuine nature.