Germany, Anonymous or Inanimate

The German elections have brought controversy to a disciplined regularity that is well illustrated by the latest Berlin projects of Grassi or Kollhoff.

Berlin is Europe's autumn and spring. In the clamor of the September 11 commemorations, we forgot that although the 21st century effectively began with the destruction of the WTC towers, the 20th had already ended on November 9, 1989 with the fall of the Wall that had defined the contours of the Cold War. In the course of the long decade that separated these demolitions (on one hand the joyful excitement of Berlin’s 11-9, on the other the confusing horror of NewYork’s 9-11) Europeans closely watched the temperature of Germany, converted after reunification into the continent’s gravitational nucleus: postwar stability had depended on its disciplined domestication, but after the thawing, the future of the Union urgently rested on its protagonism. During this period, the Balkan wars showed that the economic giant remains a political dwarf, and Berlin’s reconstruction showed how the demographic colossus suffers from chronic indecision. Urns now may clear some dilemmas, but the urban landscape of Germany’s capital will continue being built with the uncertain pulse of late.

The spirit of the ‘new simplicity’, that was imposed as an aesthetic guideline in the reunified Berlin, survives a decade later in works such as the Walter Benjamin Platz by Hans Kollhoff and Helga Timmermann.

The at once monumental and domestic city of Schinkel was also the crowded, unhealthy ‘Berlin of stone’of Wilhelm, the effervescent crucible of the interbellum avant-gardes, and the urb divided by the Cold War that revealed its scars as well as its guilt. After the fall of the Wall and the subsequent transfer there of federal institutions, the recuperated capital was regenerated with as much physical energy as symbolic indecision, split as it was between the continuity of the old fabric and the innovation of techniques, between the anonymity of urban guidelines and the singularity of the exception, between the severe regularity of urbanism and the emblematic spectacle of architecture. Under the rigorist mantra of ‘new simplicity’, the city rebuilt the grand axis of Friedrichstrasse with stone fac-ings and homogeneous openings, proposed for Alexanderplatz a nostalgic Manhattan with massive 30s style skyscrapers, and raised in Potsdamerplatz a new shopping and office district using 19th-century urban schemes and contemporary signature architectures. It is the latter operation that includes the recently completed complex by Giorgio Grassi, a project the Milanese architect understands as a critique on Berlin’s restrictive planning guidelines, but which at the same time illustrates the intimate uncertainty of a city eager to p

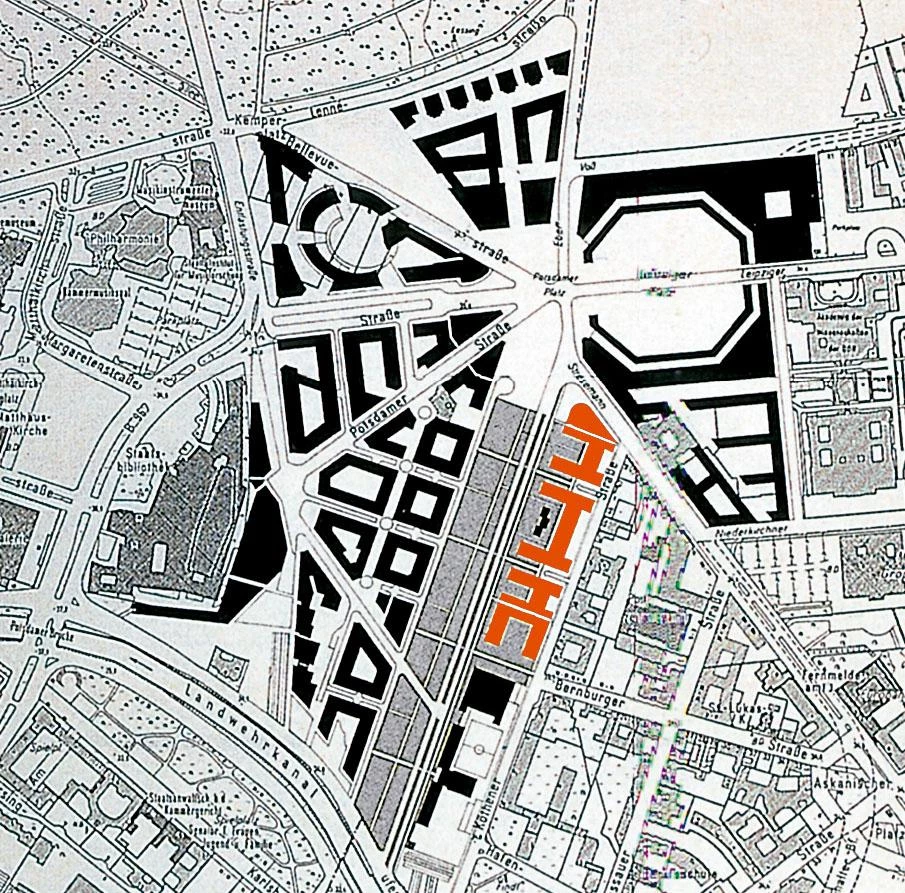

With its 19th century plan and signature buildings, Potsdamerplatz sums up Berlin’s latest urbanism. Giorgio Grassi laid out one of its sectors with five U-shaped blocks, executing with his severe language the two central ones.

South of Tiergarten and adjacent to the Kultur-forum that is home to Scharoun’s Philharmonie and Mies’s Neue Nationalgalerie, the Potsdamerplatz area was a huge space whose proximity to the Wall had kept dramatically empty, and that with reunification had retrieved its old strategic condition as a hinge between Baroque Berlin and the new city. For this privileged zone, the urban authorities decided to recuperate the traces of the old trident of streets and the conventional scheme of city blocks, partitioning it into three sectors that were acquired by three multinational companies: Daimler Benz, which entrusted its part to the Genovese Renzo Piano while assigning buildings to Rafael Moneo, Richard Rogers, Arata Isozaki, and Hans Kollhoff; Sony, which commissioned its large triangular city block to the Chicago-based German Helmut Jahn; and Asea Brown Boveri, whose lot was divided by Grassi into the five blocks now almost completed (the curved glazed piece at the end by the Berlin ar-chitect Peter Schweger, the first two H-shaped blocks by Grassi himself, the third H by Berlin’s Jür-gen Sawade, and the U block with horizontal fen-estration by the Swiss Diener & Diener).

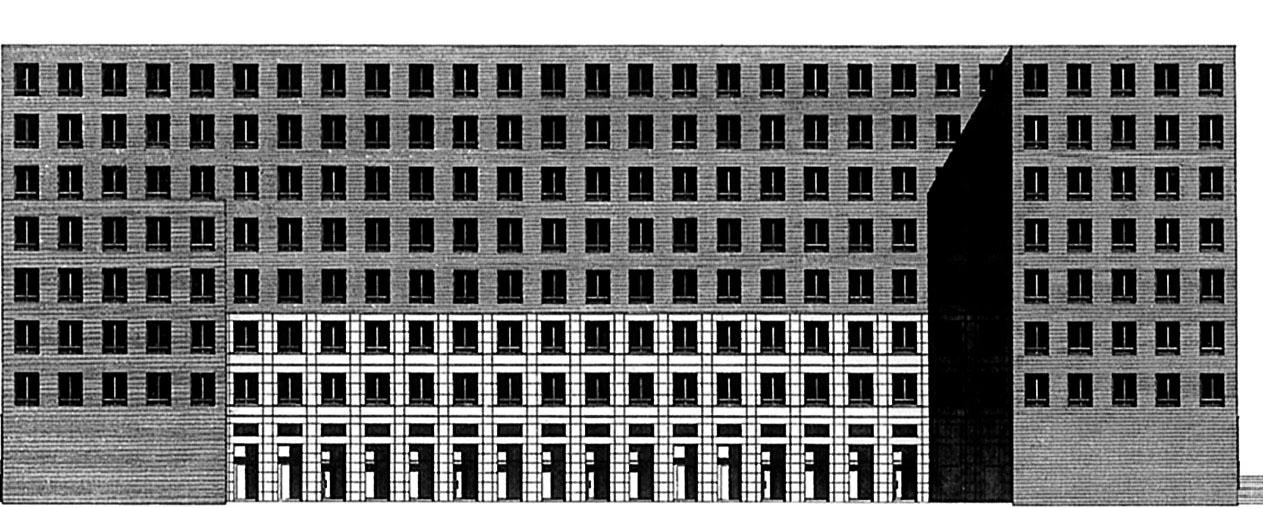

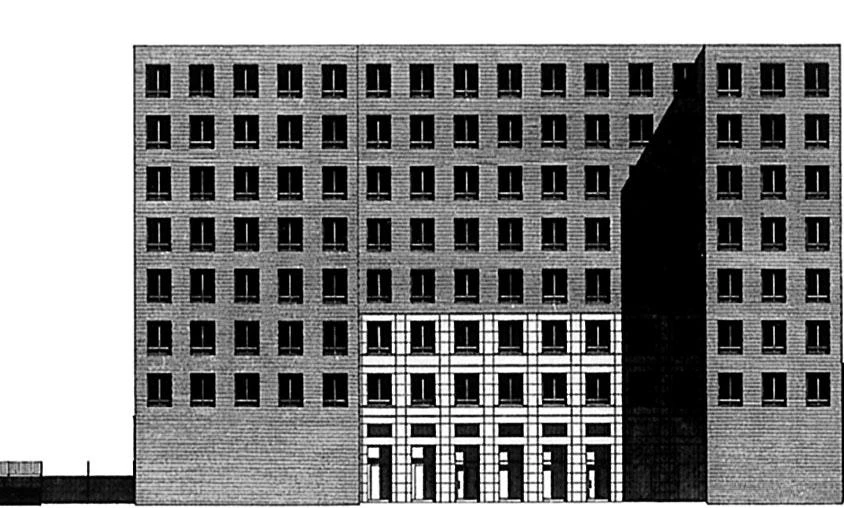

The German Kollhoff takes the Tuscan piazzas as reference in his Walter Benjamin Platz (above and below), whereas the Italian Grassi pays tribute to Hilberseimer with his Potsdamerplatz offices (below).

The Daimler Benz and Sony sectors were wrapped up in the last three years, and both the jumbled up ceramic-faced buildings of Piano and other invited stars, and the exhibitionistic technological fanfare of Jahn, were received with a bittersweet combination of popular success and critical censure. One wonders if a similar reception awaits Grassi’s recently finished project. Certainly it is dif-ficult to predict public acclaim for this monotonous and implacable complex, metaphysical in the extreme abstraction of its brick prisms dotted with openings arranged with obsessive regularity, and hermetic in the stone veneer that marks the height of the Baroque city; only the spatious courtyards that open onto the adjoining future park (laid out, like the buildings, over the old terrains of the Potsdamer Bahnhof) and the easy connection to the metropolitan and suburban railway lines (provided by the pavilion that stands in the courtyard of the central block) will make citizens appreciate it. Nevertheless, it would be very unfair of critics not to praise the intellectual caliber and rough refinement of a proposal which, by scorning the amiable entertain-ment of its neighbors, defends the contemporary va-lidity of the heroic modernity of Hilberseimer, there-by returning to Berlin the same German lesson of rational rigor that the Italians of the Tendenza had received from Mies and Tessenow.

In simultaneous concordance and contrast with Grassi’s work, Hans Kollhoff and Helga Timmer-mann recently terminated in Berlin’s Charlottenburg quarter a town square of rigid regularity whose drily monumental geometry of pietra serena seeks to evoke the vegetation-free piazzas of Tuscany, but whose naked perspectival solemnity and compositional articulation of porticoes, pilasters, moldings, cornices, and balusters also recalls inevitably the imperative classicism of national-socialism. Kollhoff, who has erected on Potsdamerplatz a historicist skyscraper characterized by austere graveness, and who won the competition for Alexanderplatz with a bunch of Rockefeller Center replicas, tackles Walter Benjamin Platz with two sober blocks of dwellings and offices whose cold precision and rhythmic regularity are indeed a paradoxical tribute to the fragmented and aphoristic philosopher of the Passagen-Werk (not to mention the irony in ded-icating this authoritarian architecture to a persecuted Jew who killed himself in Port Bou).

Like the author of the federal buildings, Axel Schultes, or like the Sawade who is working with Grassi on Potsdamerplatz, Kollhoff is a disciple of Oswald Mathias Ungers, the rationalist master of this generation of northern Germans, an architect who has been more fortunate with his theoretical projects than with his schematic works, but who deserves credit for having kept alive the flame of the Prussian tradition of formal rigor. The fire that once consumed Grassi still feeds the Milan-Berlin axis; but that same virtuous monotony is now lost in the labyrinths of Germany. Refloated by the floods, Chancellor Schröder has faced Stoiber’s Bavarian populism with mediatic seduction and rhetorical pacifism, paving for his country a path that diverges from that of the Empire: a bold and inconsistent decision which would be worthy of commentary if it were remotely plausible. In the final analysis, it seems the Germans do not know what is happening to them, and this is also what is happening to us.