Mitteleuropa Memories

Heritage Interventions in Czech Republic

Jože Plečnik, Jardín en el bastión del castillo de Praga

Architects are taught to materialize what springs up from blank paper, but the challenge we face nowadays is not so much to build, as to build on the already built. In light of the visual thinking that comes with the craft, combined with the training that sustains it, this revolves around an increasingly pressing pole: heritage. A pole which – ever since it began to be taken into consideration in the 19th century, with the heated debates between followers of Ruskin and Viollet-le-Duc – has not ceased to bring up problems and paradoxes, and remains far from resolved, even conceptually.

Heritage is literally “what we receive from our parents,” and this definition points to the first snag in any intervention on an inherited construction: working on a diachronic project that must take both past and present tense, the times of progenitors and offspring, into account. Depending on which direction architects are more inclined toward, they risk turning dogmatic, sometimes succumbing to the advocates of pure restoration, other times siding with those who simply despise history. But here, too, virtue is the mean between extremes, and though it is true that the most valuable monuments demand respect through contained restorations, whereas those of less interest ask for upgrading through straightforward touch-ups, there is a very broad field in which the best option seems to be the analogical project that does not simply imitate forms of the past, setting out instead to learn from the monument, study it closely to respect its type, its materiality, and its atmosphere, and strike up a dialogue with it.

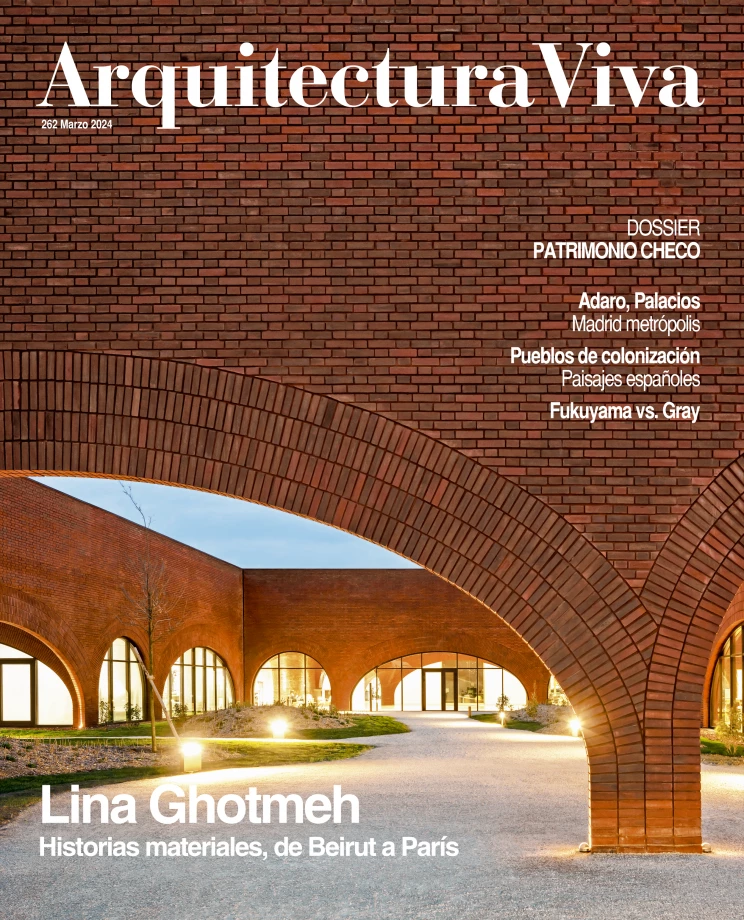

Interventions of this kind are what we have chosen to feature in a dossier which on the other hand focuses on a country with a particularly dense heritage, the Czech Republic, an enclave few can beat in possessing the temporal and cultural marriage of East and West that we associate with the evocative but imprecise term ‘Mitteleuropa.’

Each in its own way, the three works show how a dialogue can be struck between the past and the present. Located in the northeastern city of Ostrava, the PLATO Contemporary Art Gallery by KWK Promes is the result of acting upon an old but monumental slaughterhouse of brick through strategies like emptying, cleaning, enlarging, and replicating certain lost elements. For its part, the revitalization of the Vltava River’s banks as it runs through Prague is a more urban and collective effort that has managed to clean up and unify a heterogeneous waterfront formed by 19th-century edifices, with newer standouts like Frank Gehry’s ‘Ginger and Fred.’ Finally, the reconstruction of Helfštýn Castle in Týn nad Bečvou by Atelier-r insightfully applies the best approaches to analogical intervention, completing a spectacular ruin with new elements that respect the original monument.

John Pawson, Monasterio en Novy Dvur